The Babri tape starts with the title credits. An effect resembling a pen writes the name Newstrack in blue against a red backdrop. Cut. A master shot with the anchors framed against a reddish background provides a solemn introduction. Cut. The highlight reel begins. Each highlight reel freezes to an image. The anchor announces the headline – “Ayodhya, Blow by Blow: Demolition and its Aftermath.” Freeze frame. Fade to transition. Back to the anchor’s studio. In a sombre tone the anchors introduce the context of the Babri Masjid (Mosque) demolition. Meanwhile, images from the story are being flashed against the backdrop. Freeze frame. Cut.

Situated in Northern Uttar Pradesh in a town called Ayodhya, the Masjid site has been a flashpoint between Hindus and Muslims for years. The mosque was built during the Mughal era, although Hindu right-wing groups asserted that it was built over a holy Hindu temple (mandir). Throughout the 1980s, the issue was taken up stridently by Hindu fundamentalist groups with the political support of the Bharatiya Janta Party (BJP), until the demolition of the site in 1992.1 The significance of this event is twofold: on the one hand, it was instrumental to the rise of BJP, the current ruling party in India. On the other hand, the video magazine Newstrack’s coverage of the Hindu majoritarian movement mobilising against lower caste and Muslim minorities re-politicised the media landscape. As Arvind Rajagopal’s (2001) work on television demonstrates, media reshaped the context in which Indian politics was conceived, framed and enacted. Video magazines like Newstrack not only transformed the way news stories were presented and circulated in India, but also brought stylistic innovations (including camerawork and editing) that remain important for understanding the connection between video publicities and populism today.

In this essay, I offer a critical historical analysis of the video news magazine Newstrack, focusing on its coverage of the Mandal-Mandir period (1989-1992). Launched in 1987, the video news magazine Newstrack emerged as an audiovisual avatar of the print format and was the first current affairs program that circulated on videotape in India. The Mandal-Mandir affair came shortly after with the Mandal commission’s recommendation of 27 percent reservations for Other Backward Castes (OBC) in government jobs and public universities, thereby pushing the total reservations to 49.5 percent.2 Such an affirmative action recommendation was implemented by the V.P. Singh-led government in 1989 and attracted sharp criticisms from various sections of society, notably upper castes, which led to student agitations across the country. These agitations took a violent turn when a student named Rajeev Goswami immolated himself, inspiring the self-immolation of other students and contributing to a mobilisation for the Babri Masjid demolition movement in Ayodhya. The demolition movement demanded the construction of a temple (Mandir) on the premises, which consequently led to the riots in Bombay in 1992. Captured by Newstrack and circulated on what is now widely known as the “Babri tape,” the protests and demolition still persist in public memory as witnessed by annual commemorations in the Indian news.

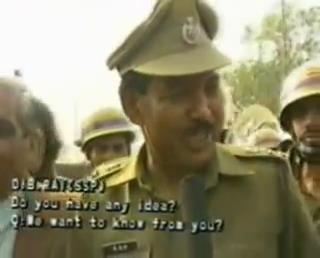

In Newstrack’s Babri tape Hindu fundamentalists are shown destroying the Masjid while firebrand orators address a massive crowd. The story begins alongside the voiceover of a correspondent. The camera has a hand-held immediate feel to it with zooms and flash-pans used to capture the destruction of the mosque by the mob and the failure of law enforcement officers to intervene. The sequence is structured with cuts to not just move from one location to the demolition site, but also to move across time with the speeches and interviews of right-wing leaders, kar sevaks, the district magistrate, and the police personnel. The story is composed of several long shots to provide a sense of space and convey the magnitude of the event. Several scenes have words bleeped out in speech and subtitles. It ends with a freeze-frame of the demolished structure before segueing into a break which contains many advertisements.

The Babri events illustrate Dilip Gaonkar’s (2014) claim that riots are symptomatic of social rupture, the rupture being a result of disappointment and unmet expectations of the populace. Gaonkar’s observation rings true for countries like India, which with all of its diversity of class, caste and religion is also a deeply unequal society. It is this inequality that fostered caste and religious resentment and led to the events of the Mandal-Mandir moment, which continue to have a lasting impact upon the Indian polity. What I want to draw attention to here is the curious relationship between social rupture and analog video news. Between the early 1980s and the mid-1990s, analog video was a pivot point between the technologies of film and television. Prior to video, news shot on film reels needed to be developed and duplicated before audiences got to see them (often months later) projected in a theatre. At the opposite end, television news transformed liveness and immediacy through the use of satellite and cable, among other technologies. Analog video existed between these two paradigms; it recorded unfolding events and circulated them on videotapes, with a lag time as short as 15 days. It therefore fostered changes in everyday understandings of newsworthiness, liveness, and the event, and introduced new modes of production, distribution, and reception. In the absence of any access to state-controlled broadcasting, the video news magazine in particular proved to be an important technological, aesthetic and infrastructural intervention. The images above were captured by the video news magazine Newstrack and were not broadcasted on Indian television, which at the time was controlled by the state. Their significance is demonstrated in testimonies of viewers who recall the day of the event and reading about it in the newspapers. They eagerly waited for a copy of Newstrack to come out, as the state-controlled television did not broadcast it. My own father recalls not finding a copy of the magazine in the neighbourhood library, while my mother remembers the community screenings of the video magazine organised in her neighbourhood.3 I was told that this version was a bestselling episode of the magazine. Such an anecdotal evidence encapsulates Newstrack as a repository for video events in the country.4 In this essay I want to suggest that Newstrack became a repository of video events and, as such, a critical infrastructure for India’s emergent media populism. By focusing on the Mandal-Mandir protests, through a combination of archival documents, field interviews and textual analysis, my aim in this essay is to trace the importance of the video event as an affective force in Indian politics in the 1980s-90s, in order to tease out tensions between state and private controlled media, populist irruptions and sensationalist imagery. Before turning attention towards a definition of the video event, however, I think it important to understand the origins of Newstrack in technologies of television and print culture.

The Material and Aesthetic Infrastructure of Newstrack and the Video Event

Television in India started in 1959. It was state-controlled and known at the time as Doordarshan. Doordarshan began its broadcast with three prime motives: “To educate, to inform, to entertain” (Sinha, 2005). Stylistically, Doordarshan represented the state through its coverage of political parties and leaders engaged in various activities, such as public speeches, inaugural ribbon-cutting, and parades. According to Somnath Batbayal (2014), Doordarshan can be divided into three phases. The first phase (1960s to the 1980s) saw the employment of Doordarshan as a socio-economic educational project for villagers and later as a state propaganda tool for nation-building. In the second phase, which lasted through the 1980s, the state controlled the airwaves and private sector commercial engagement in order to legitimize televisual entertainment. In the third phase, the state ceded control and allowed private players the chance to broadcast programmes on Doordarshan. Newstrack emerged and declined during the second and third phases of Doordarshan.

Newstrack is also linked to the history of the print magazine India Today,5which was founded in 1975 and run initially as a family business. The family patriarch, Vidya Vilas Purie, owned Thompson Press; his family had roots in a printing plant, and only later diversified into publishing. He started the magazine along with his daughter Madhu Trehan, who became its editor; her brother Aroon Purie oversaw the magazine’s basic operations; her sister Mandira was a staff photographer. Initially, the magazine was envisaged as a news-oriented magazine for Indians living abroad. However, its original 5,000-copy print run was also targeted at the domestic markets as an experiment, one that proved to be a success. The magazine flowered in the post-emergency era, particularly with the sordid scandals linked to the Maruti project and the Shah commission hearings.6 Its style was chatty and informative, which contributed to an exponential increase in the circulation figures.

India Today was the first magazine to enter Afghanistan during the Afghan-Russian war, and it was the first to contact the rebels following the entry of Soviet Troops. The magazine also ran stories on the Tamil Tigers in Sri Lanka, the death of Sanjay Gandhi, the assassination of Zia-ur-Rehman and other global events.7 It is this legacy that influences Newstrack’s representation of news.

According to Ravi Sundaram, by the late 1980s formal and informal infrastructures became the centre of media circulation through an entanglement of people, objects, knowledges and technologies in the post-colonial world. To think through the emergence of the infrastructure of Newstrack, I draw upon Brian Larkin’s (2013) formulation of infrastructures. Video, in this article, is understood both as a medium – the physical material such as videotape, VCR’s, and formats such as VHS – as well as an infrastructure.8 This includes the production, circulation and distribution practices that utilized video. In India, the 1980s saw an influx of video cassette recorders (VCR’s) into the domestic space, and both video and TV were supported by a vast underground of piracy through video libraries and video parlours. Informal circuits of distribution democratized media watching practices in a country where access to legal media was limited, and thus novel infrastructures disrupted models of the management of public affect via authorized circulation channels (Sundaram, 2003). Newstrack emerged as a reaction to the state-broadcaster Doordarshan policies. Under the Rajiv Gandhi government, Doordarshan had given free reign to both fiction and nonfiction programming. This openness came to an end in 1986, and motivated journalists to explore the possibilities of the medium of video in terms of production, circulation and distribution in order to disseminate news that ran counter to the official version propagated by Doordarshan.9 My infrastructural understanding of video technologies demands tracking the production and reception practices accompanying forms such as the video news magazine and to ask how they engaged with the prevailing socio-cultural changes of the period.

The video magazine was first introduced in India in 1987. While the first video magazines to arrive in the Indian market were entertainment magazines, Newstrack was the first current affairs video news magazine. Led by Madhu Trehan from India Today as its editor-in-chief, its team was made of 20-25 people, mostly fresh graduates who lacked formal training before they joined the magazine and learnt the visual grammar on the job.10 The departments included cameramen, editors, correspondents, advisors and researchers. Infrastructurally, Newstrack was shot on analog video cameras, and was made available to view on rented video cassettes that came with a subscription to its print sister India Today, or at video libraries across the country. The production, post-production and the overall setup involved the use of their own video cameras, ENG equipment and editing machines. They also rented special effects equipment.11 Newstrack had a tie-up with a courier company so that copies reached subscribers sooner based on their ‘news value’. Although piracy affected the sales of the magazine, it did well financially, as advertisements never released on state-run Doordarshan found their way to the Newstrack tape.12 This distribution model differentiated Newstrack from the broadcast model. Moreover, the material infrastructure of Newstrack helped it craft a visual grammar that was distinct from state television.

Newstrack was immediately perceived as an alternative to Doordarshan and what was dubbed as its ‘dreary current affairs programming’.13 Perusing through the media coverage this seemed to be the dominant sentiment with the print media dubbing the magazine ‘Video as Doordarshan’ and ‘Newstrack: alternative to Doordarshan’.14 TV critic Amita Mallik stated, ‘DD being what it is it certainly needs competition in the field of news and current affairs. In that sense, I think Newstrack is a very good idea because it can give us what DD leaves out’.15TV and Video World commented on Newstrack’s coverage:

One can’t really complain that people who are not really newsmakers are shunned. The pavement dwellers of Bombay, the child labor bondage in the carpet weaving belt of Mirzapur, Benares, Badol, etc. point towards Newstrack’s almost conscious inclusion of this class that so badly needs exposure but is always almost neglected by the news media.16

‘There was a felt need for news magazines because television was state controlled and objective news on visual media was non-existent’, stated Vivek Sengupta of India View produced by Independent Television.17 Anil Dharkar, then editor of the daily Mid-Day stated that:

…with Newstrack you have a real alternative to DD, in the sense that you get a news based programme which shows you things as they really are, rather than the way the government wants you to see them. I foresee more and more of these things coming up.18

Dubbed the ‘newsmagazine to watch’19 and aimed at the English-speaking audience, the video magazine was indeed political in nature and contained features unheard of in Indian electronic media. In her work on the political documentary, particularly the one made on the Narmada Bachao Andolan, Bishnupriya Ghosh (2009) analyses how testimonies from heterogeneous constituencies combined with moving camera shots create a sense of an immersive cinema. This idea of testimonies seems to be present in the political video news magazine as well. Many press outlets noticed that the subjects covered by the magazine were almost always neglected by news media; in this manner, it opened the eyes of the viewers to a wide range of subjects and issues. The general expectation was to make Doordarshan news wilt under pressure. However, its editor-in-chief, Madhu Trehan, asserted that Newstrack was not an alternative to Doordarshan:

No. I don’t see ourselves as an alternative. We are not really competing with DD in any way. We don’t come on the same time as they do. If we did on another channel, then we would be competitors.20

Whereas the infrastructure of Newstrack indicates the material pre-conditions of a model of news that circulated on video to emerge in counter-response to the state broadcast news, Sundaram’s observation suggests to me that Newstrack emerged through analog video as a force of disruption which calls for the conceptual category of the video event, so as to pay attention to longer media histories that help to understand the shifting contestations around state, politics, media and populist tendencies. For these contestations to manifest, sufficient attention must be paid to the material and aesthetic infrastructure of Newstrack.

News of Newstrack’s launch made rounds in the press in early 1988. Covering the first issue, Playback and FastForward ran the headline, “Video as Doordarshan: Will the absence of good coverage on TV ensure the success of news cassettes?”21 In a piece entitled, ‘Video Magazines: The Medium is the Message’,22 the journal Playback and FastForward stated that:

In the video field the Indian Market has shown far more dynamism than the rest of the world… In software, too, no other country has exploited the magazine concept as India… It would not be too surprising if the effort of India Today is a frontrunner worldwide in using the video medium as a journalistic tool… The effect of the video medium will be felt thereafter by DD, promising some improvement in TV.23

In his discussion of video art, Sean Cubitt notes that video has a tendency to ‘do broadcast things without broadcasting, filmic things without film, to do documentary, to be confessional, to tell stories, to play with illusion’ (2006: 44). It was as if the machinery of video seemed ‘too simple, too direct, to be capable of lying or lying badly’. Former Newstrackers assert that Newstrack was not about breaking news but about making sense of news. By this, they meant that formally every news story was given 30-45 mins of space on the video cassette, it was an investigation of news, where one would go through a story in greater detail. Prashant Sareen elaborates on this:

People were used to government style news reels, stories of the government media whereas in our stories there was the handheld camera and NG (not good) takes, there was this whole sense of immediacy in the way it was being shot unlike DD where the camera was stationery. Our cuts were faster, our shots were graphic.24

In the case of the video news magazine, the close-up transformed into jerky, hand-held movements that provided a sense of dynamism and immediacy to the news events captured and watched by audiences on the television screen at home. Through these aesthetic devices, the video format sought to make sense of events and not just present it. It is in this making sense of news via Newstrack’s use of visual grammar where the potentiality of populism resides, and it is Newstrack’s visual grammar that I conceptualise as the video event.

What then is a video event? To conceptualize the video event, I draw upon the debates established around the media event. The video event is characterized by interruption, immediacy and present-ness. However, these qualities can be found in the media event as well. Theorists of the media event have noted ‘interruption’ as one of its major characteristics (Dayan and Katz, 1992; Wark, 2005). But media events are also inherently processes of mediation. Joanna Zylinska and Sarah Kember (2012) argue that mediation is ‘disclosed in media events’ and thus open up our awareness of being in the world. Thus, media events become performative in their effect. Newstrack functioned as an interruption not only in the events covered by the magazine but also as an interruption in the way news was broadcast in India. Newstrack therefore embodies a process of mediation, as it aesthetically crafted a new language for news broadcast in the Indian mediascape. The difference I want to specifically make between the video and the media event is the way spectacle is represented. In the media event the spectacle is associated with grand events, broadcast on television and composed of long shots and dynamic movement. The video event is characterized, by contrast, by its use of the close-up, shaky pans, the zoom lens and a sense of intimacy.25 The video event is located within the analog infrastructures created by Newstrack and participates in events that imbibe populist tendencies through its use of stylistic devices and mode of affective address. With this in mind, I now turn my attention towards the magazine’s coverage of the anti-Mandal protests.

The Mandal Tape and the Video Event

If Newstrack’s rise and significance lay in its coverage of the anti-Mandal protests, I now want to suggest that video constituted a crucial role in understanding this moment which critically delineated the tensions between the state, publics and media. Regarding the demolition of the Babri Masjid and succeeding events, Arvind Rajagopal (2005) argues that they were embedded within the logic of the televisual event, specifically the broadcast of the mythological epics Mahabharata and Ramayana on Doordarshan. However, these epics constituted only one part of the media landscape at the time. Video occupied its own position as oppositional media and covered these events which were not broadcasted on Doordarshan.

The anti-Mandal agitation was covered in the September and October 1990 editions of the Newstrack magazine. The September edition showed the beginnings of the protest, with groups of students, doctors, lawyers and educationists taking to the streets. The camera used long shots to give a sense of the numbers agitating against the implementation of the commission’s report. Zoom in. Cut. Close-up of a hand covered in red. Cut. Protestors huddled and screaming on top of a bus. Fade to transition. Interviews of stakeholders, including politicians and journalists, on the issue. The framing is a mid-shot. Cut to protest. Scenes of tear gas being deployed and flash pans of students running away with the police cracking down on them.

While not usually regarded as ‘populist’, the anti-Mandal protests do exhibit certain populist tendencies. Here, I use the phrase ‘populist tendencies’, because it is the elites who feel betrayed and hurt by those in power rather than the marginalized.26 In particular, populist tendencies preyed upon a notion that upper caste, Hindu interests were being subverted by the government in favour of those belonging to the lower caste or being Muslim. Such a sentiment prompted Hindu groups to agitate in order to take back their primacy and power, and was exploited by the right-wing Hindutva Bhartiya Janta Party that supported the Babri Masjid demolition.

Newstrack covered the anti-Mandal protests with an obvious anti-Mandal bias. Madhu Trehan, the anchor, proclaimed on the cassette, “V.P. Singh has the blood of the students on his hands.”27 This is further amplified in the October 1990 edition of Newstrack where the anti-Mandal protests appeared more violent. The tape begins with the anchors declaring in a sombre tone that this tape ‘is dedicated to all young men and children who lost their lives’. The tape depicts an ‘unimaginable backlash of violence’ with the highlight reel showing vignettes of a student immolating himself, the pelting of stones and use of tear gas and bullets, framing it as ‘turbulent times’. The story begins with a freeze frame of a young man Devendra who was shot by the police and subsequently died in the hospital. The scene shifts to INA Market in Delhi where there are sounds of bullets reverberating. The camera jerks to capture the source of this noise. Cut. Close-up of bullets lying on the street. The camera pans furiously to capture the battle between the student protestors and the police. Cut to a man bleeding. The cameras jerkily follow the police as they pick up the protestor who was bleeding profusely and then carry him to the car. The camera closes in on his upper body from where blood is oozing out. Cut to protestors holding up the bullets and displaying them for the camera. Cut to women protesting and charging at the police battalion. Fade to transition. The camera pans to show the police stationed everywhere across the city. The scene shifts to Aurobindo place market in South Delhi, where a stone-pelting battle is going on. The camera showcases the funeral procession of the student with a close-up of the corpse. Cut to scenes of immolation. Cut to an interview with Rajeev Goswami. The camera then cuts to close-ups of the burns inflicted on the bodies of all those who lost their lives during this agitation.

The images described above conveyed energy and dynamism with jerky, handheld movements and fast, rapid cuts. This was in sharp contrast to Doordarshan, that always tended to use static frames and smooth camera movements enabled by the tripod. Moreover, the calm, grim tone of the commentary was at odds with the frenetic imagery onscreen.

In this stylistic rendering of two oppositional viewpoints, was Newstrack perhaps not just a witness but also a harbinger of the sensationalistic imagery we see on television news channels today? Or was this imagery produced by young practitioners discovering analog video technology and trying to craft an aesthetic form for the coverage of these events? Can this then lead us to suggest that the production of the Mandal agitation was a video event?

The production of the video event can be seen through a shifting notion of liveness. The liveness of the event compels news outlets to generate an already-known structure to the story. Zylisnka and Kember (2012) make a distinction between liveness and lifeness of media. Lifeness indicates the possibility of emergence of forms to generate unexpected and unprecedented events and connections. In this formulation, mediation is an all-encompassing process with social, economic, political, technical and psychological aspects that must be accounted for and cannot be disentangled from each other.Here, I find Jane Gaines (1999) idea of the mimesis of the political documentary a useful way to think about the ‘lifeness’ of Newstrack. Gaines refers to the presence of bodies in two locations: on the screen and in the audience. It thus addresses what the political documentary wants one to do, namely, it wants the audience to do something ‘because of the conditions in the world of the audience’, which is shown in the documentary. She argues further that to say, ‘machine’s produces the body is to say that machine discourse is powerful enough to bring entities into being’ (pp 90). The Mandal tape of Newstrack illustrates many of these creative qualities of the political documentary and its lifeness; the footage is shot in real time, capturing the immediacy of the event – the tense atmosphere between the students and the police, the pelting of stones, the retaliation with firing and the immediacy in ensuring medical attention for the gunshot victim. The operation of these events in time, simultaneously recorded through the video camera, gave the coverage a quality of unpredictability, existing outside the broadcast studio and announced and advertised in advance. The video magazine made use of video technology where the cameras, lighter than those of film, allowed their operators to capture the immediacy through zooms and flash pans, thereby anticipating an aesthetics of ‘liveness’. But the ‘lifeness’ of this event can be seen by its aesthetic affect in its production and reception.

A report in the September 1992 edition of Times of India noted that the Mandal agitation marked the success of this new medium. While students were immolating themselves in front of Newstrack cameras in August 1990, the video news magazine was cashing in on this exclusive footage. The number of cassettes it duplicated reached an all-time high of 10,000. Its success spurred the likes of Eyewitness, Observer Channel, Business Plus and India View to join the bandwagon.28 However, the Mandal edition of Newstrack attracted a fair bit of media attention with academics, journalists and ordinary citizens criticizing the magazine for its very obvious anti-Mandal bias. Madhu Kishwar criticised it for its openly propagandist role. She wrote a review based on the narrative structure of the coverage. Her critique was based on the blatantly partisan note adopted by the aggressive editorial and the barrage of emotionally charged comments. Referencing the Rajeev Goswami self-immolation and the spate of suicides that followed in its wake and its coverage in print media at that time, Kishwar wrote:

The anti-reservation movement gathered a panic momentum when Rajiv Goswami took the horrendous lead in an attempt to immolate himself. Between the 19th and 20th September 18 suicide attempts by young people followed in various parts of the country (pp 56).” She argues that “this deserved cautious coverage and that Newstrack, caught up in its righteousness, does not heed such considerations; instead, every rule of professional ethics is flouted and they do everything possible to incite young people to still greater frenzy (ibid).” She concludes that “Newstrack has been given legitimacy due to the lack of credibility given to Doordarshan that completely ignored the agitation. This led to what she terms a kind of pamphleteering journalism [that] masquerades under the self-righteous name of crusading journalism and is fast becoming the norm rather than rarity as came out clearly during the days of anti-reservation agitation. (1990: 60).

In a panel discussion at the Chameli Devi Jain awards function, held in 1993, TV journalist Shashi Kumar argued that the coverage of anti-Mandal agitations by Newstrack was partisan and oversimplified. 29 Similarly, a reader’s letter to the editor in the September 1993 edition of the Times of India made the claim that:

Ms. Madhu Trehan‘s October 1990 issue of Newstrack has earned the dubious distinction of having made the single greatest contribution to set passions aflame. The reader further observes that by, trying to wriggle out of a situation created by unfavorable criticism, Ms. Trehan today, speaks in terms of editorial stand and journalistic exercise. She forgets that she has unwittingly betrayed her feelings by referring to our children who must sacrifice their lives of Mr. V.P. Singh’s vote bank and thereby had instinctively identified herself what a senior editor has described as the bold and beautiful set. Her silence today amply illustrates the ethics of journalists who question politicians on moral lapses.30

Responding to criticism over its Mandal coverage, Madhu Trehan stated that:

Our October 1990 issue was not on the Mandal Report or issue – it was a report on the anti-Mandal agitation that gripped the country.” She further adds, “Our editorial stand was that the government had been totally unresponsive and irresponsible towards the students – if the agitation and the same footage was of pro-Mandal students, our editorial stand would have been just the same. Yes, I would have said the same thing. V.P. Singh has the blood of these students on his hands.31

The above-mentioned critique of the Mandal tape highlights a shift in the representational politics associated with images of events in the media. This is particularly apparent in Madhu Kishwar‘s analysis, which contrasts the presentation by Newstrack with the lack of coverage by Doordarshan. However, Kishwar’s focus (like that of others who followed in critiquing this particular issue of the magazine) is based entirely on the composition of the shots and the structure of the narrative. Unlike Kishwar, I recognize the camera’s significant role in generating charged emotions. This can be seen through the structure of the story, its liveness and camera movements.

My interest here is to examine the role of the machine aka the camera and how it represented these events and the effect it has on the bodies of those being filmed and those watching at home. Drawing on Gaines’s arguments, I focus on how the camera operated in the news magazine’s approach to narrative and the act of witnessing. It is the camera that produces the partisan effect. The deployment of flash pans, zoom, and jerky hand-held movements gave the anti-Mandal protests a sense of urgency. But in its coverage of the pro-Mandal positions, the camera deployed mid-shots. The excessive focus on moments of suffering undergone by the body and those watching amplified the images, thereby transforming them into events. Former Newstracker Prashant Sareen asserts that watching this moment politicised him and made him enter journalism.32 Can we extend Gaine’s point and think of Newstrack as a creator of images that evoked a visceral reaction with each story packaged as an event?

Perhaps we can find clues to the packaging of the event through the way Newstrack advertised itself at the end of each edition of the magazine. Accompanied by relevant images, the text of the advertisement stated:

If you didn’t see it at Newstrack you wouldn’t see it at all, Meham, Mandal, Ayodhaya, the first live shootout, the first time one saw militants in action, the first news channel to go to Pakistan occupied Kashmir, the first interview with Harshad Mehta after the scam, the first live TV debates on crucial debates, Newstrack blending news with entertainment, India’s top TV organisation-around the globe and India. Because first is still the best.

In the Indian context, it is crucial to understand the model of structuring events provided by video as a predecessor to the televisual event. Newstrack, with its accelerated camera movements and cuts, broke away from the model followed by Doordarshan. As evidenced through the discussion above, it elicited debate in other media spheres, such as the newspaper, and became a repository of moving image events outside of state institutions like Doordarshan. As such, Newstrack became the video sensorium of political events in India from 1980-90s and a predecessor to contemporary news on Indian television in use of its sensationalist imagery, the notion of immediacy, liveness, and its lifeness and the tensions that exist between state and privately controlled media.

The Question of ‘Liveness’

The transition from video to television was necessitated by the impact of the coverage of the Gulf war by CNN on media infrastructures. The ensuing popularity of CNN spelt the first signs of doom for the video magazine enterprise, and cable TV took over the home video market. Concurrent with the popularity of CNN was the mushrooming of private channels and cable operators in the country. Times of India noted that the launch of Star TV in 1991 was the beginning of a slow death of video news magazines.33 Reacting to this change, Madhu Trehan said, ‘we will definitely respond to the demands of the market… we are waiting for the dust to settle down before announcing our plan of action’.34 The response came in the form of Newstrack migrating from a video magazine to a programme that was broadcast on Doordarshan. The tensions between state and private controlled media are captured by Newstrack’s transition from video magazine in opposition to the state to an hour news programme on state controlled television in 1992, and its coverage of the aftermath of the demolition, which led to riots and bomb blasts in Bombay. Commenting on this change Prashant Sareen said:

We later went to DD, it was like India’s version of 60 minutes. These would be compelling and graphic stories in long form. But there was an immediacy as it became a weekly affair. It died on DD in 1997. Also, cable TV had arrived along with the dish antennae. The Gulf War changed everything’.35

This change in Newstrack can be witnessed by its interview of Yakub Memon. Yakub Memon, was a key suspect in the Bombay riots and blasts that took place post the Babri Masjid demolition.36 This particular episode created a legal brouhaha with allegations of judicial indiscipline and contempt of court levelled against the programme, as well as complaints that the media had moulded public opinion when the matter was subjudice. However, I want to focus on two things here: the staging of the interview and the question of liveness. The interview was a standard two-piece conversation. However, what had changed was the notion of liveness. According to Abhijit Roy, liveness consists of ‘a network of audiences embedded in the temporal framework of simultaneity’ (2014: 13). Liveness fundamentally provides direct access to the ‘now’ and is composed of live footage, soundtrack, text, scrolls and still images. In Newstrack’s migration from a video magazine to a broadcast programme, there is also a shift in the immediacy of the content – from a magazine that came out in 3 weeks after a major news break, the format had now shifted to breaking stories within the span of a week. Although I have not been able to access these episodes of Newstrack, my interviews have made it clear that the programmes involved fewer long-story investigative pieces, moving instead to short, crisp stories that dealt with news events immediately.

The changing nature of liveness also signals the changing nature of the video event. Earlier in the essay, I had referenced Zylinska and Kember’s (2012) distinction between liveness and lifeness, and how this distinction underlines the vitality of media. The shifting nature of Newstrack on various mediums attests to this vitality. In its video avatar, Newstrack represented issues that resonated with the masses and was generally oppositional in nature to state controlled television. It changed from an oppositional force to becoming an instrument of the state when shifting from video to television. Newstrack thus illustrates the tricky terrain of the relationship that exists amongst the coverage of political events, media and its ownership. This change was also induced by changes in technology, in the case of Newstrack, it being the transition from video to satellite television. I signal to this change and this particular broadcast, as it firstly, encapsulates Newstrack’s journey as a repository of video events to one co-opted by the state in its television avatar over the course of three years while covering the events of Mandal-Mandir moment. Secondly, the coverage of the events of Mandal-Mandir, highlights the rise of majoritarian tendencies becoming mainstream in Indian political discourse.

While South Asian media and film scholars of this period focus on Doordarshan as a tool of state propaganda or discuss the pirate form of video, scant attention has been paid to the way video energised new aesthetic forms and addressed both everyday life and political unrest. The magazine itself became an event not only in the way it addressed news stories but also in its clamour to get the latest issue out in the form of footage not found on television. It is important to note that Newstrack was the precursor of one of India’s largest and most successful Hindi 24/7 news channels, Aaj Tak, which increasingly oriented itself to audiences during Newstrack’s broadcast avatar using the slogan ‘the news you need to know’. Currently, its legacy has been reinvigorated again as it is again being broadcasted as a daily 1 hour programme on Aaj Tak’s sister English language channel, India Today. The media theoretical analysis of Newstrack offers a framework to think about 24/7 and digital video news forms and its relationship to polity.

Post Script

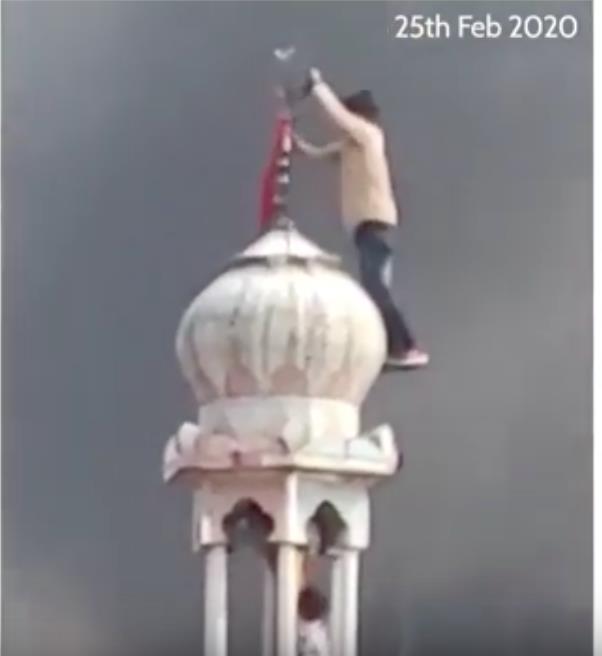

The conceptual category of the video event, arises via an infrastructural and aesthetic perspective, which in turns widens the notion of media of that represents, captures, or highlights events, but also plays a crucial role in producing and shaping social and technological process. In this essay, I carried out a media theoretical analysis of Newstrack and its coverage of the Mandal-Mandir events- events which were crucial to rise of Hindu nationalism in India. While, it’s difficult to make a direct causal link between the video event and manifestations of the Hindu right wing, the analysis of Newstrack indicates that the creation of video events, generates public debate and gives representational and socio political space for national populisms to flesh itself out. Thus, I end this essay by coming back to an image from the Ayodhya clip (figure 1.15) showing the mosque dome with men on top raising saffron flags. The image has now become iconic, and the footage is still used by news channels and digital news media outlets across the board as archival material. The photograph encapsulates the Mandal-Mandir moment in Indian politics and how the video event interrupts prevailing aesthetics through its visceral style and public affect. Currently, this image finds itself back in public conversation with the riots that took place in New Delhi in February 2020. The riots erupted in North East Delhi, when a local leader belonging to the BJP incited the mob to clear out a protest sit-in site comprised of and led by Muslim women against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA). Images, still and moving, real and fake, proliferated in real time on 24/7 news channels and social media platforms like Facebook, TikTok, Twitter, and Whatsapp.

One such image that stood out was a rioter placing a flag on top of a mosque that was attacked (Fig 1.16). This image has uncanny similarity to the demolition images of the Babri mosque in 1992, a fact noticed by those on social media, who circulated the two images side by side. Separated by nearly three decades, these images highlight populist tendencies, mainly majoritarian in nature, in the contemporary Indian polity. In particular, they bring into relief how the video event transforms itself technologically and aesthetically in capturing these tendencies. In the latter example, the video event is shot on mobile phone cameras, morphed for social media, and broadcasted immediately on 24/7 news channels and social media platforms. It is also circulated by protestors across the political spectrum to make their arguments. Through the image of the Delhi riots, we observe how public affect and populist tendencies have been merged and transformed by video practices, over time, and thus the centrality of the 1980-90s video cultures for understanding more recent media political irruptions. Newstrack fostered an aesthetic sensibility and infrastructure, which started in opposition to the state, but in the long run got co-opted by both the state and its opponents in order to mobilize crowds and open up modes of contestations.

The case study of Newstrack illustrates how analog video cultures can serve as one key vector to historicize and contextualize digital technologies and their relationship to contemporary politics. While I use the conceptual category of the video event in relationship to Newstrack in India in this essay, the video event can present itself as a generative concept to think through other political contexts and video populisms (before and beyond and dominant digital technologies).

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank Joshua Neves, Katherine Newman, Rachit Anand, and Anirban Gupta-Nigam for their comments and reflections that informed this essay.

Notes

1. According to Christopher Jaffrelot (2007), the Hindu nationalist movement started to monopolise the front pages of Indian newspapers in the 1990s when the political party that represented it in the political arena, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) rose to power. This ideology assumed that India’s national identity was by Hinduism since it represented around 70 percent of the population. Its motto, ‘Hindu, Hindi, Hindustan’, echoed other European nationalisms based on religious identity, a common language, or even racial feeling. Ayodhya, is the birthplace and capital of the god-king Lord Rama. The site was supposedly once occupied by a Rama temple until destroyed in the sixteenth century on the orders of Babur, the first Mughal emperor, and replaced by mosque, the ‘Babri Masjid’. Hindu fundamentalist groups called for this site to be returned to the Hindus in 1984.

2. Reservation in India is affirmative action for backward caste and tribe in government jobs and higher educational institutions. Schedules castes, schedules Tribes, other backward castes and economically backward are those who are included. According to Thomas Blom Hansen (1999) the ―Mandalisation of the political field in the late 1980s has often been interpreted as a watershed in Indian politics and the beginning of a new phase in which the poor and lower-caste majority began to assert their rights against centuries of tyranny by upper castes (Omvedt 1991). The entire issue of caste-based reservations seemed, however, neither to upset nor challenge the logics of the majoritarian democracy.

3. Interview with Prashant and Rachna Tiwary, Delhi, July 3, 2016.

4. Interview with Madhu Trehan, Delhi, Nov 25, 2015.

5. The License Raj also known as Permit Raj was a system of regulations, licenses and accompanying red tape that were required to set up and run businesses in India between 1947-1990. It came from India’s decision to follow the planned economy model which meant that all aspects of the economy were controlled by the state and license were handed out to a select few. Private companies could produce if they were granted a license by the government and agreed to be regulated by the government.

6. In 1977, India Today uncovered the racket around Maruti Udyog Ltd. They labelled it as Sanjay Gandhi’s small car racket. Initially, Maruti was supposed to be a 100 percent Indian owned company to manufacture cars made in India for Indians. However, through India Today it came to light that that there was an intense race amongst international car companies to become the government’s partner in Maruti. The Shah commission was instituted on June 1, 1977 to look into the excesses committed during the Emergency. It was headed by a former justice of the Supreme Court, Justice J.C. Shah. On June 20, the commission made an announcement asking the Indian public to submit their claims by August 1 and they received an overwhelming response. The complaints were categorized and hearings began on September 29, 1977. The commission found that the emergency ordered by Indira Gandhi was not justified, and hence, special courts were setup to ensure speedy trials. These special courts were however soon disbanded as the ruling Janata Party which ordered it was voted out of power in 1980, and Indira Gandhi was voted back in power.

7. Editorial, ‘India Today looks back at its origins, evolution and the people behind its success’, India Today, Jan 28, 2014, Available at, <http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/india-today-looks-back-at-its-origins-evolution-and-the-people-behind-its-success/1/354812.html> Accessed on 24th October, 2017.

8. Brian Larkin (2013) defines infrastructure as a material form that facilitates the flow of goods, people and ideas, shapes the nature of a network and provides the architecture for circulation. Focusing on the aesthetic or what Larkin terms as Poetics will help to situate how the political is constituted through different means.

9. The Bofors corruption scandal implicated the then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and the ruling party he belonged to-the Indian National Congress. The scandal is to do with the US $1.4 Billion deal in the form of illegal kickbacks between the Swedish Arms Manufacturer Bofors and the Government of India for the sale of 410 Howitzer guns, and a supply contract almost twice that amount. The scandal motivated the government to use Doordarshan as means to keep a strict check on programming and to become its mouthpiece.The investigation of the scandal revealed flouting of rules and bypassing of institutions. It led to the defeat of the Indian National Congress in the Nov 1989 Indian General Elections.

10. Shirley Thomas, ‘Video News Magazines on the brink’, Times of India, Sept 15, 1992, pp 17.

11. Ibid, pp 18.

12. Kalpana Shah, ‘Tracking Success: The Newstrack Story’, TV and Video World, 01/11/1989, Vol 6, Issue 11, pp 17.

13. Anuradha Chopra, ‘Wheels within Wheels’, Times of India, Oct 23, 1988.

14. Video as Doordarshan’, Playback and Fast Forward, 01/10/1988, Vol 3, Issue 5, pp 78.

15. I.M. Rana, ‘Changing Trends’, TV and Video World, 01/08/1989, Vol 6, No 8, pp 35-43.

16. Ibid, pp 41.

17. Shirley Thomas, ‘Video News Magazines on the brink’, Times of India, Sept 15, 1992.

18. Rakesh Rajan, ‘The Video Decade’, TV and Video World, 01/11/1989, Vol 6, Issue 11, pp 34.

19. Video as Doordarshan’, Playback and Fast Forward, 01/10/1988, Vol 3 Issue 5, pp 78.

20. Kalpana Shah, ‘Tracking Success: The Newstrack Story’, TV and Video World, 01/11/1989, Vol 6, Issue 11, pp 18.

21. ‘Video Magazines: The Medium is the Message’, Playback and FastForward, 01/01/1988, Vol 2 Issue 8, pp 45-7.

22. Ibid.

23. Ibid.

24. Interview with Prashant Sareen, Delhi, Nov 25, 2015.

25. Elsewhere I have argued that the medium of analog video is characterized by the use of the close up and zoom lens and hence becomes a medium of intimacy as opposed to film which is a medium of spectacle. I arrive at this argument through interview of practitioners of this period. The practitioners observe that as opposed to film video has a lower latitude, was seen on the small screen i.e. television, could not be shot on low light since it generates noise and causes significant generation loss with every copy. For detailed discussion on this see Tiwary, Ishita, ‘Analog Memories: A Cultural History of Video in India’, unpublished PhD dissertation, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, 2018.

26. Here I draw upon Gaonkar’s definition of populism on the basis of three characteristics. First, the invocation of the doctrine of popular sovereignty: people are the sole source of political authority and legitimacy in a democracy. The rationale for the existence of any polity, especially one democratically elected, is to serve the people as a whole by promoting the common good and collective welfare. Second, the current government and the ruling elites have failed over an extended period of time to discharge their duty. Instead, they have subverted the democratic system itself, including the constitution, to promote their own class interests, at the expense of the general public interest. Third, it is time to take the government back from the conniving elites and to restore the primacy of the people. The power of the elites, to the extent it is not eliminable, should be severely curbed and carefully monitored.

27. Newstrack Tape, October 1990 edition.

28. Shirley Thomas Bajaj, ‘Video News Magazines on the Brink’, Times of India, September 15, 1992; Interview with Vineet Narrain and Rajnessh Kapoor, Delhi, 29th Jan, 2018.

29. Times News Service, ‘Mandal, Ayodhya coverage flayed’, Times of India, May 30, 1991.

30. Bulbul Ghosh, ‘Sound and Fury’, Times of India, October 13, 1993.

31. Sabina Sehgal, ‘All quiet on the anti-Mandal front, Times of India, September 22, 1993.

32. Interview with Prashant Sareen, Delhi, Nov 25, 2015.

33. Shirley Thomas Bajaj, ‘Video News Magazines on the Brink’, Times of India, September 15, 1992.

34. Ibid.

35. Interview with Prashant Sareen, Delhi, Nov 25, 2015.

36. Staff Reporter, ‘Explain Yakub Interview, judge tells CBI’, Times of India, Aug 11, 1994.

References

Batabyal, S. (2012) Making News in India: Star News and Star Ananda. New Delhi: Routledge.

Basu, T. & Sarkar, T eds. (1993) Khaki Shorts, Saffron Flags: Critique of the Hindu Right. Delhi: Sangam Books Ltd.

Blom Hansen, T. (1999) The Saffron Wave: Democracy and Hindu Nationalism in Modern India. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Cubitt, S. (2006) ‘Grayscale Video and the Shift to Color.’ Art Journal 65.03: 40-53.

Dayan, D. & Elihu Katz. (1999) Media Events: The Live Broadcasting of History. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Gaines, J. (1999) ‘Political Mimesis.’ in Gaines J & Renov, M. eds. Collecting Visible Evidence, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

Gaonkar, D. (2014) ‘After the Fictions: Notes towards a Phenomenology of the Multitude’ E-Flux 68.

Ghosh, B. (2009) ‘“We shall drown, but we shall not move”: the ecologics of testimony in NBAdocumentaries’ in Sarkar, B. & Walker, J. ed. Documentary testimonies: Global Archives of Suffering. New York and London: Routledge.

Jaffrelot, C. (2007) Hindu Nationalism: A Reader. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Kishwar, M. (1990) ‘Instigators of Hysteria: Role of Media during Anti-Reservation Agitation’, Manushi Number 63-64:

Larkin, B. (2013) ‘The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure.’ Annual Review of Anthropology 42.1: 327-343.

Rajagopal, A. (2001) Politics After Television: Hindu Nationalism and the Reshaping of the Public in India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001

Roy, A & Sen, B. eds. (2014) Channeling Cultures: Television Studies from India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Sinha, D. (2005) ‘Development (without) Communication: Viewing Doordarshan Methodologically.’ Journal of the Moving Image. Web. Accessed on 16th November, 2016.

Sundaram, R. (2010) Pirate Modernity: Delhi’s Media Urbanism. London and New York: Routledge.

Sundaram, R. (2015) ‘Post-Postcolonial Sensory Infrastructure’ E-Flux 64.

Wark, M. (2006) ‘The Weird Global Media Event and the Tactical Intellectual’ in Chun, W. & Keenan, T. eds. New Media, Old Media: A History and Theory Reader New York: Routledge. Zylinska, J. & Kember,S. (2012) Life after new media: Mediation as a Vital Process. Massachusetts :MIT Press.