Island Fever:

Videated Populism and Disputed Geography at Sea

Weixian Pan

The vernacular expression Hulianwang de haiyang in Chinese can be translated literally into ‘Internet (as) Ocean’. The term captures a correlation between the vastness and unpredictability of both the Internet and the Ocean, the difficulty to navigate them and the necessity to monitor and regulate them. At times, ‘Internet (as) Ocean’ prioritizes the image of the Internet as a smooth surface, capitalizing its economic potential for global communication. For instance, Chinese telecommunication companies refer to their roaming services as man you, which literally means ‘swimming in the world of communication at your free will’. Other times, the term emphasizes the sheer amount of information and data to legitimate various practices of Internet policing. The conflicting oceanic imaginaries embedded in popular Chinese Internet expressions bring forth unruly conceptual waters and direct my attention to one of the most disputed maritime territories – the South China Sea.

Rupert Wingfield-Hayes’s 2014 BBC report ‘China’s Island Factory’ was one of the earliest close coverages of artificial islands in the South China Sea, bringing the massive scale of land reclamation activities into public view. China is certainly not alone in the frenzied construction of islands on disputed reefs and rocks. By 2015, Taiwan had constructed a small fisherman settlement and Taiping Cultural Park on Itu Aba Island, the largest land feature in the Spratly Islands that has access to fresh water. Malaysia stepped into the reclamation race after 2015 and has mainly constructed vessel ports in the Southwest Clay Reef and Sin Cowe Islands. According to estimations from the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, China’s land reclamation projects spanned from Johnson South Reef and Fiery Cross Reef to the Mischief Reef and created about 3,000 acres of new land to date, making China the leading player in this island fever.

Emerging artificial islands in the South China Sea raise two connected issues for this article. First, under the current Law of the Sea, the artificial structures are perceived as para-legal or illegal entities and do not hold any substantial maritime rights and political power. This externality to international law and sovereignty at sea is repetitively captured as a matter of ecological categorization: ‘Are they islands, rocks, or reefs?’—a problematic framing that hinders our understanding of these new structures (AMTI, 2015). Second, the controversial race of island building has put the disputed archipelagos under constant surveillance and processes of mediation, including satellite imaging, military footage, news coverage, and Internet videos to data maps and simulations. Processes of mediation turn the heavily guarded territory into a terrain where ‘viewers only see and experience the dispute and the region through circulated media images and videos’ (Hochberg, 2015). Hence, while few of us are able to travel to the disputed sites, through these contested forms of mediation we nevertheless experience the South China Sea on a daily basis.

Yet in contrast to the media’s explicit presence in the region, there has been a limited amount of critical scholarship examining how mediation actually works in this highly unstable region. In recent popular and academic literature, the land reclamations in the South China Sea are understood mainly through political-economic approaches, but seldom as an issue of media or media space.[i] In China’s official documents, for example, the Twelfth Five-Year Plan for National Ocean Development (2013-18), communication media is never discussed as a strategic focus despite the fact that telecommunication (tongxin) is occasionally credited for sustaining regional surveillance and maritime safety (SOA, 2013).This is particularly problematic given the dual transformation happening in the region. Large-scale anthropogenic activities are drastically changing the ecological landscape, and these environmental transformations are highly mediated and distributed as part of the political reconfiguration currently underway.

In light of these concerns, this article starts with the premise that the region’s physical opacity determines the centrality of mediation in understanding its political and legal tensions. Following this premise, I bring together two presumably unruly and ungovernable territories—the Internet and the Ocean—to scrutinize the complex geopolitics in the artificial island controversies and the relationship with ‘media populism’. As a theoretical framework, the Internet/Ocean assemblage unfolds through various dimensions: popular discourses, material infrastructures, and forms of mediation. Internet/Ocean first invoke the vernacular cultural imaginary of ‘Internet (as) Ocean’ in the Chinese contexts that I elaborate in the opening paragraph, while materially signaling the recent infrastructural expansion of mobile telephony and Internet networks in the South China Sea.[ii] But in this article I mainly focus on the overlapping legal discourses and contested mediation revolving around the proliferation of artificial islands in the South China Sea. Putting the two entangled forms of (il)legibility together—artificial islands and Internet videos, my goal is to challenge certain notions of ‘legitimacy’ set by the existing legal and political framing and start to speculate on the heterogeneous mediascape of a disputed region. Furthermore, compared to more politically registered forms of mediation, such as satellite images, videos are less recognized, lacking a robust understanding of their political purchases. In this sense, thinking about the Ocean and the Internet as co-constitutive realms, this article argues that videos occupy a central rather than a marginal role in this emerging digital-political geography at sea, and that they afford and constitute engagements with the changing oceanic territories and hyper-building of islands (Ong, 2011).

My use of ‘populism’ deserves some clarification, especially given the difficulty of pinpointing the term’s definition and its relation to media. Following Ernesto Laclau (2005), I perceive populism not as defined by its various historical articulations but through its ability to intervene in the political sphere and to allow ‘the people’ to emerge as a political category. This alignment with Laclau’s redefinition serves several purposes throughout this article. First, it distances itself from a presumed notion of populism in contemporary China, whereby the state actively uses populist and nationalist movements as a tool ‘to consolidate authoritarian rules’ and ‘to avoid domestic turmoil and enhance the one-party system in China’ (Li, 2017). Instead, this article investigates the ways populist logic intervenes into politically undetermined territories, in this case through video practices and Internet culture at large, where populism’s correlation with the state is more ambivalent and contingent than straightforward. Furthermore, by distinguishing ‘media populism’ from ‘populist media’, this article echoes the larger effort of this special issue to rearticulate the connections between populism and media. Media populism, therefore, accentuates ‘another form of infiltration of populism in the media, this time not as rhetorical and sentimental attitude [at the level of content] but as a part of the structuring logic [of contemporary media networks and practices]’ (Fidotta & Serpe, 2018). Digital videos offer a productive site to engage with these theoretical debates because of the medium’s plasticity and accessibility.

Based on these theoretical groundings, my approach differs from Andrew Chubb’s (2016a) notable effort to articulate how media shapes the discourse of the South China Sea. He argues that both state-run traditional media and online media in China are crucial to the emergence of popular nationalism, which increasingly operates as a ‘foreign policy weapon’ for maritime disputes.[iii] While I agree with Chubb’s effort to articulate the crucial role of media in maritime disputes, his argument mainly concentrates on media’s impact in shaping citizen’s political opinion, but in doing so, he simultaneously flattens both traditional media (e.g., newspapers and TV programs) and Internet-based media as ‘containers’ of political information and popular sentiment. For him, what differentiates Internet media from ‘traditional’ ones (despite this being a highly problematic categorization) is simply degrees of control and the kinds of political attitudes they produce (Denemark & Chubb, 2016: 59), rather than tracing the intricate relationship between state apparatus and a problematic construction of ‘the people’ in media production and consumption.

With this larger framing in mind, in what follows I focus on the production and aesthetics of two video mediations, which allow me to articulate the above dynamics. The first revolves around the video South China Sea Arbitration, Who Cares (Nanhai Zongcai, Who Cares) that has been circulated by the Chinese Youth League on Weibo as a populist response to the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s 2016 ruling over China’s maritime rights in the South China Sea. The second refers to videos from both Western journalists and Vietnamese marine crews. Through a close analysis of their respective aesthetics and production contexts, I argue that both videos demonstrate how ‘the people’ is constructed discursively as one yet mobilized to sustain different claims of political authority. The videated populism is inevitably tied to the disputed political geography of the South China Sea.

‘The Land Dominates the Sea’: Ecological-legal Framing of Ocean Sovereignty

The South China Sea is a semi-enclosed sea area of 1.4 million square miles, connecting the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean whereas south to the Chinese mainland. Geologically, it is a difficult terrain to navigate due to the thousands of rocks, reefs, and islands scattered and hidden across the massive ocean space. Historically, trading activities of fishermen as well as exploration by various imperial powers all left their marks on the maritime space (Hayton 2014). Closer to contemporary times, however, the South China Sea is perceived as one of the most disputed oceanic territories because of the competing territorial claims made by the neighboring nation-states: the People’s Republic of China, Taiwan, the Philippines, Indonesia, Brunei, Malaysia, and Vietnam.

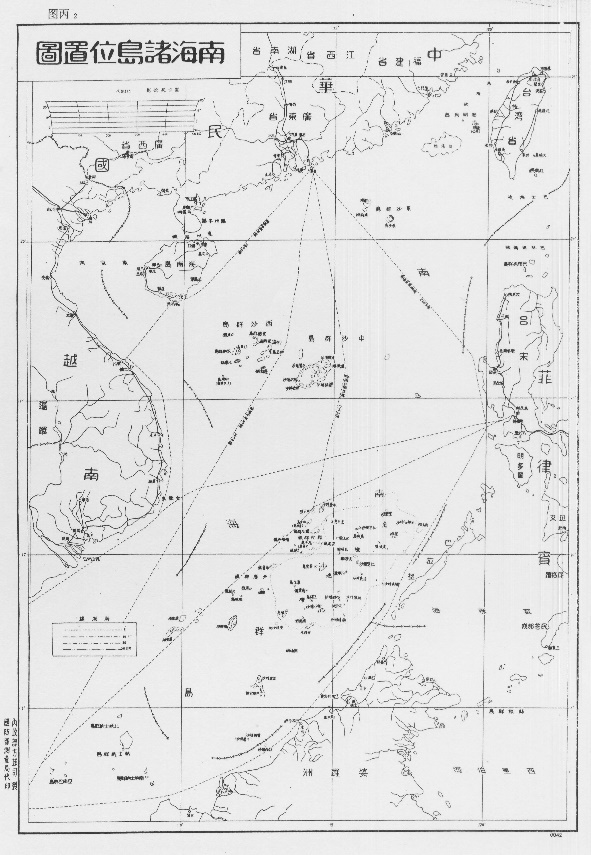

Central to this oceanic dispute are two competing logics of legitimacy, especially regarding issues of maritime delimitation. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) agreed upon certain legal categories, which allowed coastal states to claim a part of territorial water, and the right to explore its fishing and energy resources. China, however, insisted on its historic rights and claimed sovereignty over the greater part of the South China Sea. This claim was often known as the ‘nine-dash line’ drawn in the 1940s by the Prime Minister Zhou En’lai. Since then, historical documents and maps were published and updated to legitimize China’s presence and authority in the region (Heydarian 2018). What this results in is an imagined oceanic geography based on border lines that crisscross on the map (Figure 1). Because of these unresolved tensions, competing states have used a range of strategies to reinforce their claims and activities in the territorial waters: physical occupation of uninhabited land mass (putting up national flags), strengthening military presence (patrol ships, outposts), publishing historical maps and documents on early trading activities, and building temporary human settlements in distant islands.

Legal scholars and political scientists have pinpointed that international laws around legal rights over the ocean gravitate around the grounding principle of ‘the land dominates the sea’. On the one hand, this principle is a result of the postcolonial negotiation of global oceanic sovereignty. Global territorialization of maritime space can be traced back to the formative years of the United Nations’ Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which ultimately achieved to ‘subject nearly 50 percent of the world’s oceans to land-based claims of state jurisdiction’ in the 1982 meeting at Montego Bay (Chubb, 2016b). As a latecomer to the imperial game of island grabbing, China quickly followed UNCLOS’s land-centric strategies and ‘grounded’ its maritime sovereign claims into policy or legal documents, such as the 1996 China’s Maritime Agenda for the 21st Century (Zhongguo Haiyang 21 Shiji Yicheng) and the 1998 Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Exclusive Economic Zone and the Continental Shelf. Political processes of territorialization, or what Oxman called ‘the expansion of land-based territorial claims seaward’ (2006), not only have been institutionalized in international and national laws but have also manifested materially as both land-based Internet infrastructures in the region and the man-made islands that I focus on here.

The land-centric principle further sustains hegemonic ecological and legal categories that continue to shape the political geography in the South China Sea.[iv] According to the Law of the Sea, legal entitlement to territorial water is determined by ecological features, which are subjected to both quantitative measurements (e.g., tide cycles and land sizes) and qualitative evaluation (what it means to be ‘capable of sustaining human life’). While the state can exercise sovereignty over its entire land territory, it holds ‘graduations of jurisdiction’ depending on the ocean’s relation to the state’s land territories (Butcher & Elson, 2017: xxi).[v] The coast thus serves as a legal site and a metaphorical ‘baseline’ to think about issues of territory, legality, and sovereignty.[vi]As such, international laws such as the Law of the Sea normalize and institutionalize an ecological-legal construction of maritime rights that is now commonly accepted by the majority of nation states.

Part of the current uneasiness and inability to make sense of the proliferating artificial structures (including man-made islands, oil drilling platforms, and human settlements) comes from this ecological-legal framing, and the fact that it is enforced as a universal understanding of legality. As the legal scholar Davor Vidas asserts, even though the proliferation of artificial structures is essentially a result of the development of the Law of the Sea, the legal framework simultaneously denies them any legal status and thus (the islands) do not ‘affect the delimitation of the maritime zones such as the territorial sea, the exclusive economic zones or the continental shelf’ (2016). Even though they are described as an extension of the original land mass, these artificial structures cannot be recognized under the three ecological categories (only in its natural conditions) and thus remain external to the existing international legal framework.

What is at stakes here, as Truong and Knio argue, is precisely that various mechanisms of power—nation states, international laws, telecommunication companies— ‘have transformed the ocean from a “common” into what holds the characteristics of a “territory” with multiple claims to sovereignty’ (2016: 27). These historical processes of negotiating national maritime rights and international laws were eventually consolidated into China’s concept of ‘blue territory’ (lanse guotu), which literally means ‘the blue national land’. This shift from legal languages to a cultural concept, as I now turn to argue, is of crucial importance because it allows a legal discourse to enter into popular discourse and everyday media production.

Videated Populism: South China Sea Arbitration, Who Cares?

The 2016 South China Sea Arbitration encapsulates the complex legal dynamic outlined above and offers a glimpse into the entangled relationship between popular videos and political discourses at sea. In 2013, the Philippines initiated an arbitral process under the Law of the Sea. They requested to reassess certain maritime features and their legal entitlements, the claims by historical rights, and the lawfulness of recent Chinese land reclamation activities. The Philippines emphasized that their intention was not to seek ‘a delimitation of maritime boundaries’ (Kotani, 2016).[vii] Instead, this motion requested a ruling over the legal status of certain maritime features and human activities that have been at the forefront of the Philippine-China tension over the South China Sea. After multiple hearings, and despite China’s refusal to participate in the process, the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) published the South China Sea Arbitration in 2016.

One of the major pressure points in this arbitration is to re-emphasize the ecological-legal formation as the main rationale for settling maritime disputes. The arbitration concluded that the land features claimed by China, in their natural conditions, can only be categorized as low-tide elevations or rocks and thus are incapable of generating an exclusive economic zone. At the same time, the arbitration denounced any legal authority to historical rights. The PCA arbitration stated that the Law of the Sea and national historical rights are not only incompatible, but they extinguish each other’s legitimacy and ownership over the sea.[viii] Much of the subsequent discussion revolves around the ‘lawfulness’ of the ruling and its future effect on regional dynamics. While these are certainly important debates, this arbitration demonstrates an institutional refusal to engage with the ecological transformations and political contingencies brought forth by these artificial islands and other man-made structures in particular.

Shortly after the release of the 2016 SCS arbitration, the Chinese government issued an official statement that they would not recognize or accept the arbitration. The Internet then quickly became the first point of encounter between the nation-state, the disputed maritime rights, and Chinese citizens. The controversial arbitration quickly unfolded into a series of online debates. It was within such public and nationalist sentiments across the Internet that the video South China Sea Arbitration, Who Cares? (Nanhai Arbitration, Who Cares; or, ‘Nanhai video’) was published by the Communist Youth League’s official Weibo account on July 12, 2016 (Figure 2). Since then, it has been widely circulated across Chinese social media sites and picked up by a handful of Western media outlets as populist responses from Chinese citizens (Williams 2016).

In some ways, the Nanhai video echoes the rise of popular nationalism and right-wing discourses on the Chinese Internet (e.g., the ‘Wumao dang’ or ‘Xiaofenhong’ phenomenon). However, I am more interested in the aesthetic specificity of this popular video, through which to demonstrate what happens when a legal subject (territorial debates) enters everyday Internet video production. I suggest that such an outlook is helpful to rethink the problematic relationship between media populism and state power in contemporary China. Writing in the context of intellectual property, legal scholar Lawrence Liang argues that when intellectual property is transformed from a legal subject to a topic in daily conversation, this transformation indexes ‘an aggressive expansion of property claims into every domain of knowledge and cultural practices’ (Liang, 2009: 6). In a similar vein, just as territorial sovereignty is transformed from a legal dispute into an everyday topic, a certain notion of ‘rights’ and ‘territories’ bleeds into popular knowledge and media production. China’s political claims in the South China Sea—historical rights, sovereignty, resource entitlements—aggressively expand into the domain of Internet space through producing particular discursive and aesthetic forms of ‘the people’, often without a clear sense of the population involved. In this sense, while we can pinpoint a connection to the state apparatus in the video’s original release, how the logic of populism infiltrates both everyday media production and militarism becomes crucial to understand the role of ‘the people’ in territorial disputes. This tendency, I argue, manifests through the video’s aesthetics, and firstly in the deliberate usage of selfie-style recordings.

The Nanhai video opens with an uplifting electronic beat, which runs throughout the full 1 minute and 39 seconds video. In the first shot, a military-looking guy with a dark green tank top and a crew cut stands in front of the administrative map of China and is talking to a cell phone camera. Viewers can clearly hear his voice saying, ‘Nanhai Zhongcai, Who Cares?’ But the brief moment of silent mouth movement before the audio cuts in suggests that this dialogue is cut from its original context—a longer monologue that is unknown to viewers. Right after this opening shot, the video continues with multiple short footage from different individuals, each repeating the same out-of-context slogan. The wide black-stripes on both sides of the footage indicate that they are very likely to be captured by laptop or cell phone cameras individually, then re-assembled together afterwards. In this 24-second sequence of self-recordings, the featured individuals include young university students and middle-aged, white-collar workers and are a mix of man and women. The use of everyday settings, including sports fields, school dormitories, family living rooms, and offices, further enforce their status as ordinary citizens, and therefore speaking the voice of the people. Here, the construction of a political voice of the people, albeit problematic, is achieved through producing an aesthetics of intimacy – not only does the visual framing of the selfie create a particular affinity between the video and the viewer but it also narrows the emotional and perceptual distances between a legal issue and an everyday performance, between territorial sovereignty and media production/consumption, given that not many people have physically engaged with the disputed region.

This blurred boundary between legal dispute and everyday performance, between physical access and media consumption presented so far are quickly interrupted in the next sequence, in which the current landscape of the South China Sea is constructed through a casual juxtaposition of ambivalent aerial and television footage. The video now drops us directly into the heart of the ocean, cutting across unidentified aerial shots of the islands. One might speculate that these island imageries were originally shot through Chinese military aircrafts, which have direct access to the strictly controlled aerial space. At other times, the partial logos that appear on the top left corner imply that the footage might be recorded directly from Chinese television news. But in both cases, the production and distribution contexts for these images are deliberately erased in the process of being remediated into a video. What immediately follows then is a fast montage of various military equipment—aircraft, vessels, bases—as well as moments of military drills and operations—ocean patrolling, preparing aircraft launch, and pilots in the jets. Video viewers are once again left in the dark about the sources and specificity of the images. The visual ambivalence and uncertainty, I argue, are by no means accidental. The inability to pinpoint the layering of mediation and its political and institutional actors make these images more palpable for manipulation, and serve in part to enforce ‘we don’t care about the arbitration’ as a political message. In fact, the context-less footage delivers a rather clear message: maritime rights, even vaguely defined and identified (as in these aerial images), are enforced by an absolute authority through military power, which is a notion supported by the Chinese people.

This is certainly not a new strategy to create a united front through social media in China-related territories (Schneider 2018). What is worth noting is how this particular video reconfigures maritime authority through militarized and highly masculine visual fields, and simultaneously asserts such an authority as part of the people’s voice as highlighted in the previous selfie sequence. To some extent, the last montage sequence attests to this confluence: the politicization of everyday media engagement and the militarization of maritime authority in regional disputes. As the screenshots illustrate, the video now cuts between two kinds of shots: One features headshots of cute young girls with animated filters who are repeating ‘Nanhai Arbitration, Who Cares?’ The other captures moments of military attack or weapon testing—missiles launching from vessels, aircraft bombings (Figure 3). The voice of ‘the people’ is now feminized whereas the political statement continues to carry a sense of ultra-masculine militarism.

In this sense, this hyper attention to the video itself highlights how populism as ‘a structuring logic’ manifests through practices of ambivalent remediation, constructions of ‘the people’ through visual aesthetics, and a discursive formation of state authority through performing femininity/masculinity. Furthermore, this logic should not be understood as a persistent force against the state, and in the case of Chinese Internet, it emerges more as problematic ruptures of populist practices often work in tandem with state-led narratives. We may then think across media practices from meme-making, forum debates, to voluntary campaigns on e-commerce platforms to boycott products from the Philippines as various manifestations of the corrupted political potential of populism.

Video as Anti-Satellite

In the remainder of this paper, I will closely examine one of the central tensions in the Chinese digital-maritime environment—between the normalization and institutionalization of satellite imaging and what I call ‘speculative mediation’ which is offered through less legitimate media forms such as videos. My approach here speaks to two particular provocations of ‘speculation’, giving the concept more analytical traction. On the one hand, Ned Rossiter and Soenke Zehle propose that in a time when ‘uncertainty is circumscribed by risk analysis, prediction has been accorded the status of a core cultural technique. […] speculation offers a utopian gesture’ (2017), which allows us to remain attentive to conditions of distribution and mediation. As such, understanding the South China Sea as a speculative digital space puts pressure on the distinctive way digital infrastructures—telecommunication, satellite networks, and Internet services—are distributed. Meanwhile, it probes how theses infrastructures influence the conditions of mediation around the regional sovereign disputes, particularly regarding the artificial islands. On the other hand, I am also greatly influenced by anthropologist Aihwa Ong’s notion of ‘speculation’ as an anticipatory logic of economic, political, and aesthetic gains deeply embedded in sovereign power and global capitalism. Drawing from experiences of Asian urban experiments, Ong argues that the rule of political exception allows the continuous rezoning of urban spaces, and the sovereign rule helps to produce spectacular architectures that ‘attract speculative capital and offers itself as alleged proof of political power’ (2011: 207). It is in this sense that I borrow her notion of speculation in order to make sense of the geopolitical ramifications of the hyper-building of artificial islands in the South China Sea.

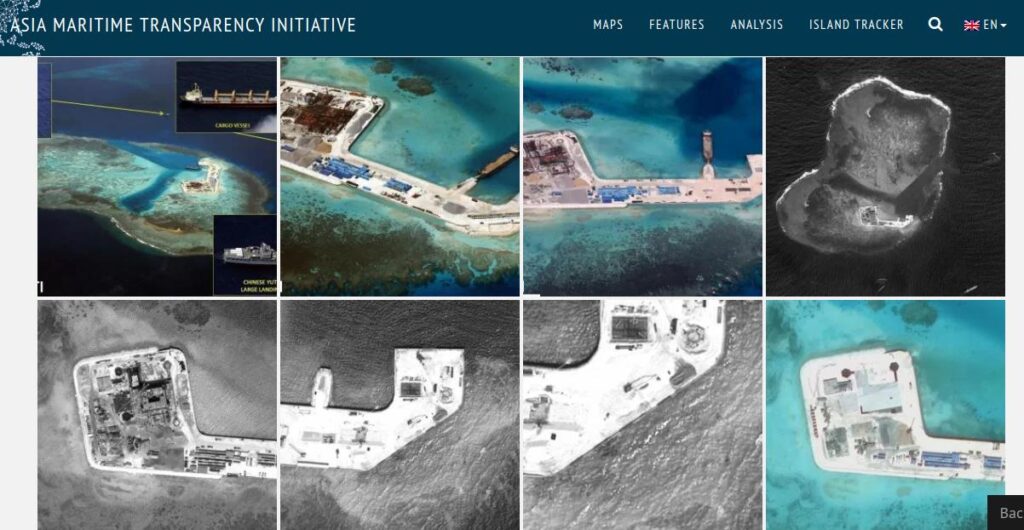

As Lisa Parks notes, when technological visions are practically intervening into every domain of life, the important task is to ‘demilitarize military perspectives, to open the satellite image to a range of critical practices and uses’ (2001: 589). Following Parks’s provocation, I question the authority and truthfulness granted to the technologized satellite visions, particularly through the island tracker project of the Asia Maritime Transparency Institution (AMTI). In doing so, I further propose that the videos’ particular technical and aesthetic intimacy to the sea should be seen as significant sites to make sense of the political contingencies in the South China Sea dispute.

Satellite data and Automatic Identification Systems (AIS) have become increasingly crucial in tracking the South China Sea disputes, especially after the controversial island building activities. AIS has long been used in monitoring maritime traffic and is required as part of the vessel requirement,[ix] but the terrestrial-based AIS has its technological limits because it is unable to keep up with the demands of surveillance and tracking the large scale island building activities that have occurred since 2013.[x] While the shift to satellite-based AIS might have initially started as a technical issue, satellite imaging quickly dominated the visual knowledge production of the South China Sea. This is partially the result of commercialized satellite services and data collection. Satellite imaging services, such as Digital Globe and Airbus Defense and Space, actively ‘track’ military and civilian activities in the South China Sea that are often restricted and only for national security use. These satellite images have been integrated into part of our everyday media practices through commercial Internet services such as Google Earth. Moreover, they are not only considered as open-source intelligence for regional disputes but also circulate as ‘evidence’ of China’s progress in land reclamation in global media coverage.

The establishment of the AMTI, a para-national research institution operating under the Washington DC-based nonprofit Center for Strategic and International Studies, signals a broader trend in pushing the gated South China Sea into public debates. Collaborating with corporate satellite imaging services, AMTI stands at the crossroads of governmental, corporate, and security efforts to transform militarized oceanic geographical knowledge to everyday media practices. Island Tracker is among the most important projects initiated by AMTI, and it aims to track the ecological transformation and progress of land reclamation across the Spratly Islands by China, Taiwan, Vietnam, and the Philippines (Figure 4). The tracker uses a series of satellite images and aerial photographs to present a linear transformation of certain coral reefs, from their natural condition to their current states as artificial islands, potentially holding civil and military infrastructures. These serial satellite images are juxtaposed and shuffle between overviews of the whole islands, close ups of unidentified island structures and vessels, and images marked with arrows and labels. The islands’ ecological transformation is most stunningly marked as a spatial disorientation through its shifting color scheme. For the undeveloped reefs, the multiple layers of green and blue shades immediately situate these islands in close relation to the water. The emerging yet unidentified artificial infrastructures, on the other hand, are marked by a monotonous white surface scattered with gray stripes and black dots. The artificial infrastructures in these images are usually disproportionate in scale and constructed as alien to the natural, oceanic environment. The ‘island tracker’ in this sense speaks to the larger military and civil efforts, eagerly identifying the political meaning of the black dots and gray stripes.

Furthermore, the particular ways these images are organized into ‘a series’ or ‘a track’ in fact erase the institutional and political conditions within which these images are produced, circulated, and why they are solicited and arranged in this way. The fact that satellite images of the South China Sea are presented in unspecified fragments produces more speculation than evidence. More often than not, these images are referenced out of their immediate contexts. Technologically, viewers are unaware of whether an image is produced by a commercial or military satellite, patrolling aircraft, or UAV. It is also extremely difficult to pinpoint precisely which island is captured in the image and when exactly it was produced. The ambiguity of how mediation happens not only conceals the process of filtering through various governmental, military, and commercial institutions but also gestures to the obscure political agenda through an orbital view of the disputed islands.

The screenshot (Figure 5) above presents part of the visual tracks for the Johnson South Reef (Chi Gua Jiao), offering an example of the attempt to construct a friction-free, linear temporality despite the disparity in the aesthetic, infrastructural, and political features embedded within these satellite images. Even though the website specifies the particular date when this image was taken, these eight serial images are clearly marked by different aesthetic and political traces. On the top left, the aerial overview of the island is marked-up in great detail—direction, specific types of vessels (cargo, construction), precise name and number of the Chinese landing ships, and institution logos ‘CSIS/AMTI’. Even without knowing who or when these markers were made, we can infer that this aerial image can be easily circulated within different media and political narratives by news coverage outlets. Other images in the series, however, display a more ambiguous relation to each other. The contrast from black-and-white to color is by no means an aesthetic choice, it indexes the different images sources—they are likely to be taken by satellites owned by different countries and institutions and some older models are not equipped with color cameras. The missing logo also indicates that some of these images come from external sources rather than produced and owned by the CSIS research institute. The forth image on the top, in particular, seems out of place in the ‘tracks’ given its aesthetics of abstraction, it does not resemble reality. As Lisa Parks argues, these ‘aesthetics of remoteness and abstraction make its status as a document of truth very uncertain and unstable and open it to a range of possible interpretations and political uses’ (2001: 589). Constructing a linear narrative of ecological transformation through abstract satellite images of artificial islands, transnational institutions such as AMTI actively produce, distribute, and normalize political authority and geopolitical power animated through technologized vision. To put it differently, the technological capacity of high-resolution mediation constitutes an integral part of regional authority in the South China Sea.

However, I want to return to some of the early media speculations on what exactly China is building on those islands or, as the BBC journalist Rupert Wingfield-Hayes puts it, ‘we are on the hunt for the Spratly islands’ (2014). This ‘hunt’ for the artificial islands hinges on a discrepancy between what is shown on his GPS and what he sees through the camera. He describes the perceptual discrepancy in a poetic way, “As we get closer, to my right, I am sure I can now see something pale and sandy beside the platform. ‘That looks like land!’ I say. It can’t be. I look at my GPS. There is no land marked anywhere near here, only a submerged reef of the Spratly Island chain. But my eyes are not deceiving me. A few kilometers away I can now clearly see the outline of an island” (Wingfield-Hayes, 2014). His vivid descriptions were juxtaposed in a short sequence in which the camera cuts between close-up shots of multiple GPS interfaces on board, such as the GPS panels on the boat, GPS systems on his old Nokia cell phone, and medium-sized zoom-in shots of the alleged ‘island’ in the distance (Figure 6-7).

One the one hand, there are multiple GPS interfaces—a form of mediation through satellite signal transmission and geolocation data that offers a precise simulation of the geographical environment that might be taken as fact. On the other hand, there is the technologized human eye, through the video camera hesitantly zooming in and searching on the horizon for the island ‘that is not supposed to be there’. What is intriguing in Wingfield-Hayes’s narration and the video editing, however, is the level of certainty and authority given to intimate encounters—through human perception and video mediation over the highly technologized satellite view: ‘I am sure’, ‘my eyes are not deceiving me’. His affirmative tone creates a sharp contrast to the shaky video camera moving along with the waves, as if it is unsure what it is capturing.

This example in many ways gestures towards what I called speculative videation, contingent on both the technological and formal specificity of video. Joshua Neves proposes to use the term ‘videation’ to signal various forms of material and imaginary intimacy through video culture’s unique mediation (2017: 268). While for Neves, ‘videation’ as a concept foregrounds popular media practices excluded by hegemonic notions of digital modernity and globalization, my intention is to highlight video’s technological and formal linkages to speculation and to push against a broader political imagination often determined by commercialized datafication and high-res mediation of the ocean. As shown in Wingfield-Hayles’ videated encounter with the artificial islands, videos animate a formal resemblance between the turbulent water waves and the political uncertainty, but they also animate an increasing affinity between legal disputes and videated speculation on artificial structures in the ocean.

The Binh Minh 02 video filmed by Vietnamese civilians attests to this affinity through a particular confrontation between China Marine Patrol and a Vietnamese survey ship. During a press release in May 2011, PetroVietnam Deputy General Director Do Van Hau said that their seismic survey ship Binh Minh 02 was conducting surveys within the EEZ and continental shelf of Vietnam defined by the Law of the Sea. They encountered a Chinese marine surveillance ship, which was ‘cutting their exploration cables and violated Vietnam sovereignty’ (Voice of Vietnam, 2011). Quickly following this incident, the Vietnamese news outlet Petro Times released a video on the alleged incident and the video was soon dubbed unofficially and uploaded to YouTube. It is circulated to the public as an attestation to the claim that the Chinese vessel traversed Vietnam territorial waters and cut the oil exploration cable, prompted a wave of national angst towards Chinese presence in Vietnamese waters.

The above video recorded Binh Minh 02’s standoff with a Chinese maritime surveillance vessel from a distance. At the beginning of the video, the camera was set on board Binh Minh 02, presumably filmed by the captain or one of the crew members. Without much context, the camera quickly zoomed in and located a suspicious vessel in sight. The captain’s voice-over abruptly cut in a second later, announcing ‘OK, he [the vessel] is coming back’, as the unsteady camera tried to keep the vessel in focus. But the frame is staggered due to the turbulent movement of the ship, unable to visually pinpoint its identity. The captain then clearly identified the hostile vessel as ‘Zhongguo haijian #84’ (a Chinese marine surveillance vessel), but visually, the video struggles to zoom in further and adjust its focus. A few seconds later, we finally got a legible visual of the name on the body of the ship, confirming the captain’s previous commentary. He continued and sent a warning toward the Chinese vessel: ‘You are acting very stupidly and dangerously. Stay away from the cable. Stay away from the cable’. The repetitive call to ‘secure the cable’ created a visual expectation of seeing the act of cable destruction, but instead, the camera continues to zoom in and lingers on the ship’s logo ‘Zhongguo haijian #84’ (Figure 8-9).

The camera then followed the captain’s question, ‘do they have anything behind?’ and slowly panned right, attempting to capture an answer at the back of the ship. But the turbulent movement of the ship hindered a stable visual through the camera, as we saw the camera aimlessly moves back and forth along the hostile vessel, searching for any material traces of the cable cutting or hostile action. The search ended in vain as the viewers were left with fragmented parts of the vessel and accidental shots of the moving ocean, and the voice-over (very likely from the person filming) agreed with the camera and says, ‘uhm…cannot see’. However, we can argue that the video camera here in fact did ‘see’ more than the voice-over—it captures a speculative visual field that is open for interpretations rather than putting an enclosure.

While the viewers were never able to locate the cable or see the act of cable destruction (cutting, traversing, sinking) visually, the video continued to linger on the alleged sites of conflict, where speculative politics are at work. In the subsequent footage, the camera maintained a medium-shot with a blurry white object in the distant water, yet we were no longer certain whether we were still on board the Binh Minh 02 or looking at the same Chinese surveillance vessel we saw a second ago. As the camera panned horizontally over the Chinese surveillance vessels, the hasty camera movement back and force might be an attempt to animate the action of the hostile attempt to cut the cables (as indicated in the external video caption). What really grasped our attention here is the sound of strong winds at sea, the engine noise, and the moving waves that clearly stand between us and the speculated act of destruction. A few second later, an awkward slide-show transition brought us on board the Banh Minh 01 and Van Hoa 379, two vessels sent to inspect and maintain the damage. According to the video caption, the Chinese marine surveillance vessel managed to cut through the cable but when they returned to cut again the cable’s emergency system forced it to sink 40 meters deeper.

From the analysis above, a sense of the discrepancy is arguably established between the act of confrontation in a disputed ocean territory and its videation. On the one hand, the video’s zoom-ins generate a technical intimacy and speculative aesthetics both at the site of the incident and during the process of viewing it. Rather than demonstrating the physical actions in dispute, the video offers a speculative space through which political opinions can be enounced as populist, even though the political category of ‘the people’ remain unspecified. On the other hand, while the practice of videation does register an immediate political standpoint from the Vietnamese crew members and PetroVietnam, it is not until the video has been footnoted with political commentary, and re-circulated within historical sentiments of Sino-Vietnam relations that these media practices become a political intervention into a highly emotionally charged yet turbulent oceanic territory. In short, by going through this video at length, I mean to showcase the significant role of video in allowing populism to structure the media aesthetics of political confrontations at sea, and more importantly the ways it lends into speculative practices to produce an affinity among ‘the people,’ even though it might not be a strict political entity and such notions are conditioned by institutional agendas.

Conclusion

The dazzling speed and scale of the island building in the South China Sea generates an overwhelming amount of visual materials: satellite imaging, UAV aerial photographs, TV news footage, and citizen videos. However, these often-contested forms of mediation are distributed in the Internet without differentiation, pushing aside, among other things, the political hierarchy embedded in the process of knowledge production and media practices. Furthermore, artificial architectures on the artificial islands are perceived as material extensions of the nation-state’s territorial claims and military power, regardless of what kinds of infrastructures they actually are—technological (signal towers, solar panels, windmills), military (ports, airstrips), or civil (hospital, residences)—or how they are allowed to be seen. Therefore, within this conflict over oceanic territory, the production of media fields—what and who is allowed to be seen, and the conditions in which these fields of visions are produced and distributed—dictates hegemonic relations between human activity and ecological transformation, between national sovereignty and corporate interests at sea.

In many ways, this article only starts to outline the significance of mediation in contemporary geopolitical tensions and environmental transformations currently taking place. The long-term opacity of the South China Sea is drastically changed by the public and media attention given to large-scale island constructions. However, despite the increasing significance of video culture in the South China Sea dispute, they are yet to find a ‘legitimate’ place in both Asian media studies and the analysis of political discourses. Central to this emerging digital-oceanic environment, as the article demonstrates, is an ongoing negotiation of political legitimacy for artificial islands as well as popular videos – both are framed as either ‘illegal’ or ‘unauthoritative’. Up to this point, I have illustrated that popular media forms increasingly play a leading role in addressing, if not negotiating, legal indeterminacy over the South China Sea archipelagos. The Nanhai video in particular opens up a more complex mechanism at work when understanding how populism is mobilized in China. The carefully orchestrated visual fields—from intimate selfie, aerial photographs to television—arguably allow these illegal structures to be articulated and re-enter the broader legal and ecological debates, gaining political leverage in the region. On the other hand, the BBC journalistic video report and Binh Minh 02 video showcases how amateur-style, cellphone video recordings actively intervene into public debates of oceanic rights and territorial disputes. In short, this article situates video’s specific modes of mediation at the center of the ‘island fever’, through which speculations arise and public discourses circulate. And what lies at the center of this contested mediated geography at sea is precisely the logic of populism, as an incentive, a set of practices, and even an aspiration.

Notes

[i]. For instance, see Green (2016), Yu (2015), and Truong & Knio (2016).

[ii]. The expansion of cellular and mobile Internet network in the South China Sea is part of my larger research on Internet/Ocean, which attests to the land-centric logic not only in the legal discourses discussed later in this article, but also at the material level – the reliance upon land structures to facilitate ‘signals at sea.’ Due to the thematic focus of this issue, I will not further elaborate this point but do want to sign post it as a background for my larger argument.

[iii]. According to Chubb, there were three main mediated ways for the CCP to strategically channel popular sentiments into political opinion on the South China Sea controversy, including dependency on official information through state-run media such as CCTV channels and People’s Daily; the emergence of nationalist opinion leaders both in and outside of the military; and lastly, systematic media guidance and Internet censorship (2016a: 22-24).

[iv]. According to the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), there are three different ecological land features in territorial waters, each corresponding to legal entitlements and territorial rights, and they are:

1) low-tide elevations, a landmass that is not entitled to any special economic zones;

2) rocks, a permanent land mass above water but cannot hold human habitation, and it entitles a 12-nautical-mile territorial sea but no special economic zone;

3) islands, capable of sustaining human habitation and economic life, can generate an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of 200 nautical miles and a continental shelf.

[v]. For instance, the state holds the same sovereign power over ‘internal waters’ (e.g., rivers and bays) as its land territories because these waters are partially enclosed by land; for ‘territorial waters’, which extend up to 12 miles, the state has sovereignty yet yields the right of ‘innocent passage’.

[vi]. The concept of a ‘baseline’, from which ‘various maritime zones of sovereign rights and exclusive jurisdictions are determined’ (Vidas, 2016), precisely animated this imposed ecological differentiation so as to exercise legal authority. A ‘normal baseline’ is defined under the Law of the Sea as ‘the low-water line along the coast as marked on officially recognized, large-scale charts or the lowest charted datum’ (NOAA, 2017).

[vii]. In their press release, the PCA similarly accentuates that this arbitration does not ‘rule on any question of sovereignty over land territory and does not delimit any boundary between the Parties’, given its juridical limitation (PCA 2016: 1).

[viii]. As stated in clear terms: ‘[…] China had historic rights to the resources in the waters of the South China Sea, such rights were extinguished to the extent they were incompatible with the exclusive economic zones provided for in the [UNCLOS] Convention’ (PCA, 2016: 1).

[ix]. Ships of 300 tons or more in international voyages, cargo ships of 500 tons or more in local waters, and all passenger ships irrespective of size are mandated by the International Maritime Organization to carry Automatic Identification System (AIS) equipment.

[x]. The earth’s curvature ‘limits its horizontal range to about 74 km from shore. This means that AIS traffic information is available only around coastal zones or on a ship-to-ship basis’ (ESA 2016).

References

AMTI. (2015) ‘A Case of Rocks or Islands: Examining the South China Sea Arbitration’, Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (December 17). https://amti.csis.org/a-case-of-rocks-islands/

Butcher, J. G. & Elson, R. E. (2017) Sovereignty and the Sea: How Indonesia Became an Archipelagic State. Singapore: NUS Press.

Chubb, A. (2016a) ‘Chinese Popular Nationalism and PRC Policy in the South China Sea.’ PhD diss., University of Western Australia.

——. (2016b) ‘China’s “Blue Territory” and the Technosphere in Maritime East Asia’, Technosphere Magazine (April 15). https://technosphere-magazine.hkw.de/p/Chinas-Blue-Territory-and-the-Technosphere-in-Maritime-East-Asia-gihSRWtV8AmPTof2traWnA.

Denemark, D. & Chubb, A. (2016) ‘Citizen Attitudes towards China’s Maritime Territorial Disputes: Traditional Media and Internet Usage as Distinctive Conduits of Political Views in China’, Information, Communication & Society 19: 59-79.

ESA. (2016) ‘Satellite – Automatic Identification System’, European Space Agency (January 3). Accessed March 10, 2018. https://www.esa.int/Our_Activities/Telecommunications_Integrated_Applications/Satellite_-_Automatic_Identification_System_SAT-AIS

Fidotta, G., and Serpe, J. (2018) ‘Opening Remarks’, Seminar in Media and Political Theory: Populism. Montreal (April 13-14). Unpublished.

Green, D.J. (2016) The Third Option for the South China Sea: The Political Economy of Regional Conflict and Corporation. London: Palgrave.

Heller-Roazen, D. (2009) The Enemy of All: Piracy and the Law of Nations. New York: Zone Books.

Hochberg, G. Z. (2015) Visual Occupations: Violence and Visibility in a Conflict Zone. Durham: Duke University Press.

Kotani, T. (2016) ‘The South China Sea Arbitration: No, It’s not a PCA Ruling’, Maritime Issues (November 17).

Laclau, E. (2005) On Populist Reason. London: Verso.

Li, Z. (2017) ‘Chinese Nationalism and Populism, Political Movements and Conflicts’, Medium (June 10) https://medium.com/@ZLi/chinese-nationalism-and-populism-political-movements-and-conflicts-bc37a5084dc5

Liang, L. (2009) ‘Piracy, Creativity and Infrastructure: Rethinking Access to Culture’, SSRN Journal (July 20).

Neves, J. (2017) ‘Videation: Technological Intimacy and the Politics of Global Connection’, in Asian Video Cultures (eds), B. Sarkar & J. Neves. Durham: Duke University Press.

NOAA. (2017) ‘What Is the Law of the Sea’, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/lawofsea.html

Ong, A. (2011) ‘Hyper-Building: Spectacle, Speculation, and the Hyperspace of Sovereignty’, in Worlding Cities: Asian Experiments and the Art of Being Global (eds) A. Roy & A. Ong. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell.

Oxman, B. (2006) ‘The Territorial Temptation: A Siren Song at Sea’, American Journal of International Law 100: 830-51.

Parks, L. (2001) ‘Satellite Views of Srebrenica: Tele-visuality and the Politics of Witnessing’, Social Identities 7: 585-611.

PCA. (2016) ‘Press Release: The South China Sea Arbitration (The Republic of the Philippines v. The People’s Republic of China’, Permanent Court of Arbitration (July 12).

Rossiter, N. & Zehle, S. (2017) ‘The Experience of Digital Objects – Toward a Speculative Entropology’, Spheres Journal (October).

Schneider F.A. (2018) China’s Digital Nationalism. New York: Oxford University Press.

SOA. (2013) ‘Guojia haiyang shiye fazhan ‘shi’er wu’ guihua’ (The Twelfth Five Year Plan for National Oceanic Developments), State Oceanic Administration, People’s Republic of China (April 11). http://www.soa.gov.cn/zwgk/fwjgwywj/shxzfg/201304/t20130411_24765.html

Truong, T.-D. & Knio, K. (2016) The South China Sea and Asian Regionalism: A Critical Realist Perspective. Baden-Württemburg: Springer.

UNCLOS. United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea’, United Nations. http://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf

Vidas, D. (2017) ‘When the Sea Begins to Dominate the Land’, Technosphere Magazine (April 15).

Williams, S. (2016) “’South China Sea arbitration? Who cares?’ Chinese youngsters fight back with patriotic music video after UN tribunal ruled on controversial waters’, Dailymail (July 13). http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3688175/South-China-Sea-arbitration-cares-Chinese-youngsters-fight-patriotic-music-video-tribunal-ruled-controversial-waters.html

Wingfield-Hayes, R. (2014) ‘China’s Island Factory’, BBC (September 9). http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt-1446c419-fc55-4a07-9527-a6199f5dc0e2

Yu, P. (2016) Ocean Governance, Regimes, and the South China Sea Issues: A One-Dot Theory Interpretation. New York: Springer.