Big Bad Social Media:

Distributed Affects and Popular Politics

Bishnupriya Ghosh

One can hardly keep up with the latest emotive explosion on social media that generates a political crisis. There are those large-scale social movements of our time, vibrant, dissipating, renewing: think Arab Spring, the Iranian Green Movement, Black Lives Matter, the Hong Kong protests, the anti-CAA-NRC struggles in India, to name just a few. For the more recent popular mobilizations, the dust has not settled for the repose of retrospection even as speculation on the Twitter and teargas admixtures in them continues unabated.[i] (I note this article was written a year before the global uprisings around the George Floyd murders that have changed us all). Then there are those proverbial viral events that amplify evidence, analysis, or polemic to such a degree that their circulation contributes to substantial shifts in public opinion, sometimes with political repercussions. Consider the audio record of Jamal Khasoggi’s murder that turned a new prince into an international pariah or the cellphone footage of police beating up students at Jamia Millia Islamia University that gave rise to global condemnation of saffron fascist crackdowns on dissent. Although the jury is out on how to assess and evaluate the interface between social media platforms and street protests, it is clear that Web 2.0 social media is indispensable to political life in the 21st century. This article addresses the distributed affective politics of social media evident in unprecedented “viral intensities” (the accumulation of social media actions around particular content), especially when the impact of those intensities on systemic change is hazy at best and insignificant at worst.

More often than not, such affective politics invite suspicion of social media as an unfettered political beast. There is good reason for this. The role social media affordances play in breeding anti-sociality seems a constant: Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp foment divisive violence, as we have seen in anti-Muslim Facebook posts in Myanmar and Sri Lanka, and in the WhatsApp-related lynchings in Brazil and India. As the tip of the iceberg, they have prompted Facebook to tweak algorithms intended to realize more “local,” “trustworthy,” and “informative” news. Too often in the hotbed of ethno-nationalist and racist populisms, nothing good seems to happen on social media. And when it does, social media actions often appear too politically superficial, too thin; sometimes too trashy or tacky; at others, too deluded and clearly anxiety provoking. Whatever the diagnoses, it is unclear whether or not there is any “social” on social media. These debates over the role of social media in popular politics raise a number of questions that prompt this inquiry. When do peaking intensities on social media count as media populism?[ii] If a basic premise of populism is the articulation of a collective “we,” can we interpret unprecedented viral spreads as indicative of political participation? I start with the hypothesis that Web 2.0 operates as the affective-technological basis of media populisms—the “sensible infrastructure,” as I characterize it—because it enables a distributed affective politics. This is not to say that there aren’t extensive deliberations or debates on social media. Quite the contrary; many of us encounter a curated social media newsfeed framed with commentaries and opinions on political matters that are sidelined or even suppressed in corporate media. But I focus on a sensible politics[iii] because its operative affective-performative mode is inimical to populist styles. The unruliness of sensible politics on the street and online elicits suspicion, fear, even condemnation, as have crowds have historically. At center stage are volatile political subjectivities, unreasonable and overly emotional, acting together in viral spreads on social media.

There has been robust scholarship in recent years on networked subjectivities that explore the politics of social media habits. In Updating to Remain the Same: Habitual New Media (2016), Wendy Chun, for one, defines the networked form of subjectivity on web 2.0 as the singular-plural YOU, isolated and anonymous, but capable of enacting a monstrous chimera of YOUs, while in Never Alone, Except for Now: Art, Networks, Populations (2017), Kris Cohen describes the YOU as acting “alone together” to inhabit a group form that hovers between a population (YOUs engineered via market data aggregation) and a public (YOUs articulated together via impersonal ties). I will return substantially to their arguments later in the article; but here, my starting point is the actions of the YOUs that create, break, weaken, or strengthen the ties constitutive of the network. Both critics initiate a look into the systems, biological and technological, within which social media users operate so as to investigate not only the technological affordances and constraints of this distributed agency, but also the life forces that energize, organize, and sustain them. Infrastructure and distribution studies provide rich scholarship on the former;[iv] and there is growing interest in the latter from theorists of the cognitive sciences.[v] Against this backdrop, social media actions are articulations of self-organizing organisms within technological environments. The distributed cognition of social media users integrated into technological environments suggest that tweets, likes, and shares are biotechnical habits. But the creating, weakening, breaking or strengthening of ties are also intrinsically biosocial because these actions operate in relation to the network: that is, in anticipation of a multiplicity of YOUs. It follows that both biotechnical and biosocial articulations of carbon-based life-forms are constitutive of social media actions. To think this way is now common to media studies: mediation is an epistemological event (in the sense of reflection, representation, or even figuration) and ontological process through which humans and non-humans co-emerge. One must therefore understand the technological as those processes that interpenetrate biological, geological, or atmospheric ones, so as to transform them. Before landing on politics, one section of this essay addresses the technological and biological conditions of possibility for the “sensible infrastructure” of Web 2.0.

The conjunction of affect and technology pushes toward thinking about how social media actions “structure the field of possibility for the actions of others,” as Michel Foucault once noted of politics.[vi] In the last section of the article, I consider the degree to which unanticipated viral spreads count as popular or populist collective participation. One may argue that posing the question reads political will into part-conscious media habit. Ironical signage in recent protests “It’s so bad that I left facebook for the street!”—register doubts about making too much of political commitments from social media actions. And theorists underline the point. Even as social media users entertain illusions of personal agency or empowerment, Chun and Cohen draw our attention to the impersonal nature of social media actions. Any analysis of the privatized internet has repeatedly shown the “personal” to be algorithmically routed, a monetized commodity. Or, as we shall see, even when they are personal, viral spreads remain within virtual gated communities. The participatory paradigm, the elusive promise of the internet, the dream of unfettered reciprocities and of democratic playing fields is of the past, well before Cambridge Analytica became a catchphrase for this demise. What, then, can be made of political subjectivities that anticipate connectivity, but not necessarily reciprocity, with other YOUs? Is the desire to participate in political life—to participate, in the large and small decisions that govern our lives—entirely circumscribed? I argue that in unanticipated viral spreads we catch a glimpse of attempts to inhabit a group form other than an algorithmically-governed population: a monstrous chimera of YOUs that we might provisionally call “affective publics.” The weak collective “we” emergent in habitual micro-actions such as tweeting, sharing, or liking is a dissenting public of public cultures or zones of contestation—not the self-conscious, autotelic publics of the classical public sphere.[vii] Affective publics are not invested in political deliberations alone; in fact, they often feel excluded from the normative civil associational forms. As unruly media publics, they partake in politics whether or not they are invited to the table.

Toward the close of the article, I turn to Jacques Rancière’s Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics (2015) to better understand the improper politics of partakers as a mode of democratic dissensus. Political improprieties are, after all, endemic to the unruliness of popular movements and to populism: to consider social media actions in this light moves toward a better grasp of present media populisms. I distinguish populism as one mode of distributed affective politics within a range of popular mobilizations; some of these actually organize against populist authoritarianism. Spontaneous, often leaderless, such popular uprisings rely on social media to organize protests (traffic direction, warnings, sharing tactics, gathering resources) and to amplify words and images. Yet invocations of the popular often raise hackles. All popular styles are dismissed for their potential danger, for their unthinking progress toward a populism that ends in fascism. Such dismissals evacuate the productive role of a sensible politics that is evident everywhere. To gather around the figure of George Floyd is a sensible politics of grief and anger, maturing into concrete demands for systemic change; it is a popular politics that quilts heterogeneous social demands through a single symbol. We are constantly confronted with the “new commonsense”[viii] of crowd occupations, sometimes with long-term agendas, and at other times without. Hence it is critical to parse what appears as the unruly politics of Twitter and WhatsApp, of the street and the square.

My pursuit stems from a sustained engagement with “uncivil” demands placed against the ruling elites and/or the state in political theory. I draw on theories in the wake of postcolonial studies that account for political mobilizations beyond civil associational forms to think about improper political affect.[ix] These conversations have roundly questioned the liberal fiction of the people that seeks embodiment in the nation-state. To be sure “the people” continue to amass in parks and squares to censure the state. But in times when conspicuous oligarchies have made a mockery of that embodiment; and when increasing authoritarianism has hijacked modes of democratic representation; the people reconstitute themselves sometimes in peaceful protest and sometimes in riot against global elites (such as the ubiquitous 1%). The political force of social media actions in these uprisings is undeniable. The best evidence for this is suspending or shutting down the internet in the face of unabated protests: think of Chinese and Indian crackdowns in Hong Kong or Kashmir as instances in the past year. The call for more algorithmic control recognizes the social force of YOUs arriving uninvited to the table, attempting to structure the actions of others. This is what drives my attempt to think beyond the algorithmic capture of YOUs as populational aggregates. Such a capture has never quite stemmed political opposition. Colonial demography perfected the biopolitical compositions of the people as life-forms incapable of governing themselves; and yet it is clear from decades of postcolonial historiography that insurgencies, appearing violent and unruly to the ruling elites, continued to arise. And they still do, despite the reach of state surveillance into every aspect of life. If under colonial rule, popular movements always relied on technologies of communication that flew under the radar of colonial surveillance, perhaps because of their artisanal, low-tech in nature, this also the case today.[x] State surveillance, controls on digital freedoms, as well as network disruptions continually spawn tactical innovations that protesters share: they travel to pick up signals, they use virtual private or TOR networks, they turn to Bridgefy (an app that uses bluetooth to enable chats or tweets, using SMS to bypass bans).[xi] Such stories recognize the political force of social media actions, of tweets and chats, of likes and shares. Why else would dissenters bother with ensuring the mediatic capacity to tweet?

I analyze questions concerning the distributed affective politics of Web 2.0 through a particular viral event. The “event” inheres in the actions that proliferated around a single photograph—of a two-year old Syrian boy, Aylan Kurdi (henceforth Alan Kurdi[xii]) dead upon the beach of a fancy resort in Turkey (henceforth, the Kurdi image)—and in the immediate impact of the viral spread on citizen-led efforts to mitigate the plight of refugees into Europe. As Lin Probitz (2015) notes, the Facebook group #RTWN (#refugeeswelcometonorway) that led efforts to collect provisions for refugees in Oslo grew from 200 to 90,000 immediately after this viral spread; the U.K. Charities Aid Foundation reported a similar spike, as 1 in 3 Britons made donations for refugees. One could multiply these instances. I focus on the Twitter storm ensuing from passing on the photograph—retweeting, liking, and sharing it—which further ricocheted between media platforms. This media explosion preceded deliberations on what the image meant or what was to be done. The performative amplification of the image enabled a discursive shift in perceptions of the Syrian refugee crisis. Within a day, the image with the hashtag #refugeeswelcome changed the sense of a “migrant crisis” to a “refugee crisis.” What could have been just another migrant death in this protracted crisis was suddenly a refugee’s death, which, I argue, inevitably raised questions of social responsibility. Such a viral event affords an opportunity to consider Twitter as the sensible infrastructure of a distributed affective politics. That analysis is possible because of extant research on this event: as it unfolded, the University of Sheffield’s Visual Social Media Lab conducted a rapid response search to collate news items, forums and blogs, twitter feeds and Google searches on the Pulsar platform associated with the viral spread of this image. Their findings are presented in a series of data visualizations that map peaking intensities around the publication of the photograph. The essays in the Visual Social Media Lab’s dossier (henceforth “VSML dossier”) unpack what the panoptic aestheticized form of data visualizations might conceal, adding historical and interpretive granularity to quantitative finds.

For those looking for hard evidence on what this discursive shift meant on the ground, it is a failed political moment. More than one observer notes that, in some cases, legislation around asylum tightened.[xiii] Since that Twitter storm, more than one European nation has closed borders, erected fences, deployed coastal regulations. More importantly, the invocation of the injured refugee worthy of special dispensations became muddier still within a very short span of time. In November 2015, the Paris attacks, the deadliest in Europe since the Madrid bombings of 2004, turned the refugee into potential threat (even though subsequent investigations established the attackers as French and Belgian citizens who had not entered Europe as refugees). This debacle was closely followed by the New Year’s Eve attacks in Cologne in which the attackers were identified as men of Arab or North African descent.[xiv] In this context, the Kurdi image had a short lifespan as the lightning rod for affective intensities around the unadulterated figure of the refugee child. And it is precisely this brief temporality that makes it a choice instance of a surging affective-performative politics that seems to go nowhere and whose causal relation to systemic change remains obscure.

I. Visualizing the Creative Event

The image is unforgettable: the two-year old Alan Kurdi in a red shirt and blue jeans face down upon the beach in Bodrum, an upscale resort in Turkey. One of the twelve refugees trying to reach the Greek island of Kos, Alan drowned alongside his mother and brother. For reasons banal and profound, Alan Kurdi made major headlines within a day of Nilüfer Demir’s photographic capture for Turkish news agency, the Doğan Haber Ajansi. At 5:30 a.m. on September 2, 2015, Demir snapped the now-iconic photograph, originally one among fifty pictures. Within 12 hours, 30,000 tweets later, 20 million had shared the photograph. It had become the recursive graphic that we understand as an iconic image. Like iconic images, it endures as one of the 100 most shared images in contemporary Europe—a powerful figural trace of a protracted refugee crisis in which 4 million (in 2015) among the 11 million Syrians displaced by war sought asylum.

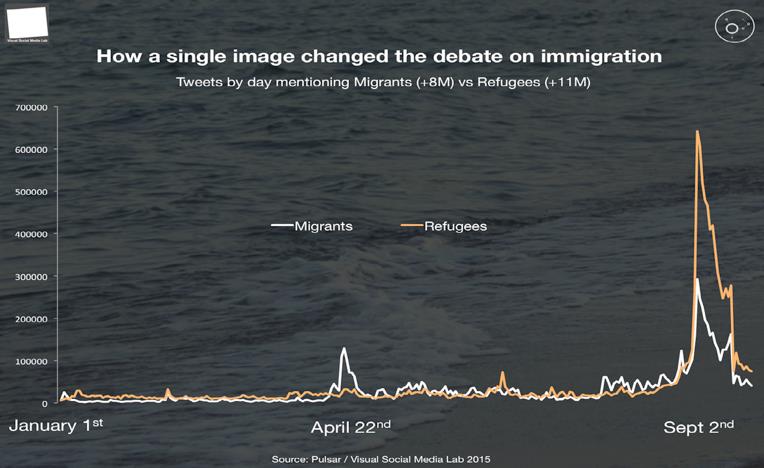

I am less concerned with the signifying power of the trace than I am with its circulation across social media, and specifically on Twitter. In the frenetic circulation of the photograph on Twitter, we see the first signs of shifting perceptions about the crisis at hand. The findings of the Visual Social Media Lab characterize the shift as a change in perceptions from a “migrant crisis” to a “refugee crisis” in a matter of days. The lab conducted a rapid response search for the 12-day period between September 2 to September 14, 2015. If for the previous nine months in 2015, the terms “migrant” and “refugee” as qualifiers to crisis were pretty much head to head—5.2 to 5.3 million tweets in the same volume of conversations—after September 2, “refugee” spiked at 6.5 million to “migrant” at 2.9 million [Fig.1].

The data visualizations document the speed and scale of signal amplification. Read together, they make legible something like a seismic shock. Qualitatively, to invoke the “refugee” meant a confrontation with social vulnerability and historical responsibility. As we shall see, key activists, journalists, and leaders had a hand in shaping such perceptions. In many instances, they rode the wave, grabbed an opportunity. But they could ride the wave because there was a new baseline for the crisis: something new had become sensible, something infectious; something that was perhaps not entirely legible.

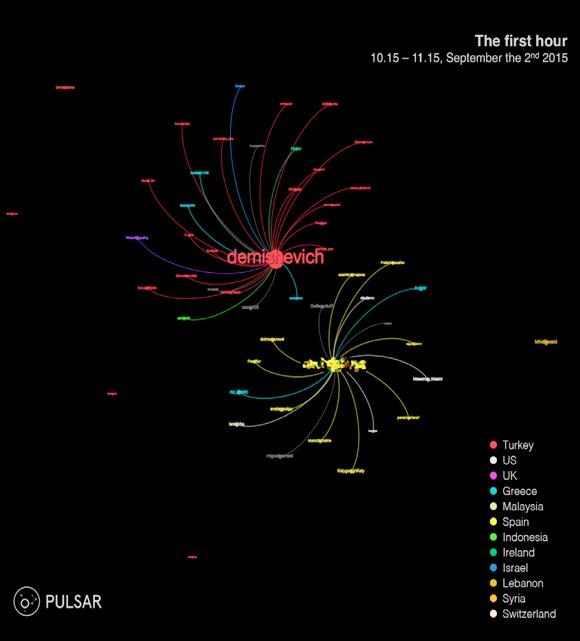

Francesco D’Orazio tracks the Twitter storm that followed the first tweet at 10:23 a.m. In that first hour, 33 retweets were mostly in Turkish; but in the next two, Turkish journalist and activist, Michelle Demisherich’s retweet with the hashtag #refugeeswelcome went viral through Lebanon, Gaza, and Syria [Fig.2a]. The Free Syria Hub quickly got in on the action, spearheading the Twitter wildfire in the Middle East. The tweets intensified when Peter Bouckaert, the Emergency Director at Human Rights Watch in Geneva urged the European community to develop a plan for refugee admission and rehabilitation. His call promoted 664 retweets [Fig.2b]. When at 12:49 p.m., Liz Sly of The Washington Post based in Beruit tweeted the photograph her tweet was shared 7,421 times in 30 minutes.By 1:10 p.m., The Daily Mail carried first story with the title: “Terrible fate of a tiny boy who symbolizes the desperation of thousands.” At the end of the day, 500 articles on Aylan Kurdi’s journey had entered the Twitterverse [Fig.3]. In this essay, I’ll focus on the Twitter storm—sudden, brief, intense—that passed on the image before the image entered the news and entertainment ecosystems.[xvi]

There is much to say about why this image caught fire. But I’ll be brief in these explanations, since my focus lies less with what it represents than what its amplification might mean. Certainly, it was chosen with care. In the VSML dossier, Claire Wardle notes that, just a couple of days before Alan Kurdi’s death, a photograph of dead babies on a Libyan Beach had surfaced, but it was quickly reported and removed from Facebook. Drawing on her experience as senior Social Media Officer at the UNHCR, Wardle’s point is that platform protocols often regulate what can circulate; they constrain the amplification of counter-speech and restrain the agency of social media users.[xviii] To these soft controls, one might add the aesthetic histories that shape viewing photographs of dead or injured children.[xix] News agencies routinely regulate tragic photographs of injured children; in this sense, these media are akin to fine art, with its historical norms and conventions. A few news platforms such as Vox and Slate initially refused to carry “gruesome images” of “dead children,” but those refusals receded after the Doğan News Agency’s tailored image went viral. In part, the photograph had high institutional credentials: it was well “brokered” before Demir’s first tweet, in all the ways that Zeynep Gursel tracks in her ethnography of news photos.[xx] Then, it was filtered through distributive chokepoints. Social media users put their trust in reputable reporters such as Michelle Demisherich and in media hubs such as Free Syria and Human Rights Watch.

No doubt the sentimental portraiture of a fully clad, middle-class boy individuated against the universal eschatological space between life and death had much to do with it becoming instantly iconic. Indeed, the Human Rights watch director Peter Bouckaert pitched his own response through his own experience as a father as did Sam Gregory of WITNESS (a video testimony platform). These are clear class-based affinities that made the image so powerful. Yet the individuated isolation of social media users makes it difficult to claim there was but one reason for the photograph’s infectious proliferation. For it is also the case that many remained unsympathetic to the image of the dead child. Mike Thelwell notes in the VSML dossier that one strain of censure saw Alan Kurdi’s death as just dessert for the boy’s father, who was reputedly a smuggler. Still others protested the indignity of circulating an image a dead child; Alan Kurdi’s aunt, for one, offered pictures of Alan, lively against a blue slide in a playground, in order to combat the tragic image. Several others saw the circulation of the image as pornographic consumption, an unethical sharing of violence that re-victimizes. The undecidability challenges attempts to extract a political position from the social media event.

Despite all brokerage, at first glance, there does not appear to be any agreement on the refugee crisis. Nor was it intelligible as carrying the burden of responsibility. The hashtag “#refugeeswelcome” was the most popular in the UK, US, Canada, Australia, India, Germany, Turkey, France, Spain, Netherlands, Austria, and Switzerland, but not in others (where the hashtag was just #refugeecrisis). In many countries, Google search terms in the week following the photograph’s publication were “What happened to Alan Kurdi?” or “Why do Syrians leave Turkey?” In Germany, a dominant query was “How to volunteer to help migrants?”; in Hungary, “How should Christians respond to the migrant crisis?”; in Italy, “How to adopt a Syrian orphan child?” And so on. The heterogeneous Google searches indicate that in fact there was no consensus over what was at stake or what was to be done. And yet, the photograph circulated, making the image of the coming refugee sensible.

II. Affect Machines

Social media platforms are affect-machines. They amplify political affects. The habits of social media users, Chun maintains, have everything to do with this amplification. But what exactly is the relation between the habitual and the affective? In the last two decades, volumes in affect studies have produced varied architectures of preconscious habit and the embodied mind. In one account, as a relationship between the body at “medium depth” (the interface between the skin and other surfaces and the greater neurological system) and the objects that it encounters, affect is a pre-personal force operative before the settling into subject-object relations.[xxi] Brian Massumi (2002) foregrounds the biotechnical dimensions of affect, an observation that is increasingly salient to the intensifying integration of biological systems with personal devices. As a student reminded me lately, Massumi’s examples of affect stitches sensation to preconscious cognition: walking down the street at night, one’s lungs throw a spasm when a shadow looms in the alley. This visceral response is not just neurological excitement but a buried memory that partly perceives threat or disturbance. So, too, with the spasm upon a screech of brakes behind you. In other words, physical stimuli—a shadow, a sound—trigger something one already knows but not consciously; not properly composed in orientations of subject (victim) and object (attacker), it elicits a conditioned response. On the other end of the spectrum, theorists such as Judith Butler underscore the biosocial inscriptions that generate affects. Over time, what was once cultural knowledge can become so deeply inscribed that it becomes a part of implicit memory and therein invokes involuntary responses. If we think these models together, internally, affects flow along “pathways” connecting sensory and neurological systems to the brain; externally, affects are responses to impersonal objects and their movements. Apropos social media platforms, integrated biological and technological systems underlie distributed cognition of media signals. That integrated system is the “subject,” argues Katherine Hayles in Unthought: The Power of the Cognitive Non-Conscious (2017), one in which the human-machine boundary has all but disappeared. Affect is what flows, what energizes the system; in this regard, affects drive habits.

Focusing on the affective terrain of Web 2.0, Joshua Neves (2020) underscores anxiety as a major problem at this human-machinic interface—so major that it is now recognized as a syndrome (Social Media Anxiety Disorder or SMAD). Re-reading Freud, Neves argues anxiety as protection from fright attaches to social media as mundane and chronic because everyday crises—disasters and catastrophes, warnings and predictions, bullying and constant exposure—keep arriving on one’s feed. This anxiety is one indicator of the anti-sociality of social media, where people and social practices (the Internet of People) become technological. Our primary intimacies are with machines: put differently, inhabiting social media is an affective-technological condition. Neves builds on Chun’s conception of habitual new media in which a singular subject, the YOU in social media, confronts constant crises.[xxii] As more than one critic has noted, crises are everyday occurrences in neoliberal times;[xxiii] on social media, the demand for real-time responsibility can prove exhausting. Turning points or thresholds, crises send the YOUs running for cover. Like all living organisms responding to change, argues Chun, they attempt to reinforce the pattern that they recognize as the “self.” This is simply protection against change, against coming uncertainties. Habit is the conditioned response that maintains the self-organizing system (the singular YOU). Turning to present neurobiological distinctions, Chun situates the habitual in sensory and motor systems that are now recognized as parts of the embodied mind. In this reading, part-conscious and conditioned, media habits can therefore seem to be de-sensitized responses to noxious signals: the rote clicking of the anger emoticon for a post of everyday mass shootings in the U.S. or on the sad icon for the most recent fires and floods. One might say that social media users who liked or shared the Kurdi image were de-sensitized to the everyday tragedies of Mediterranean crossings, and at a loss, consciously or otherwise, with regard to what is to be done. And yet, as embodied responses to change, habits, Chun reminds us, are always creative, life-giving, regenerative. Habits are repetitive actions with a difference: one constantly updates the self-organizing structure in confronting crisis. Her memorable formula, Habit + Crisis = Update, reminds us that the update “deprives habit of its ability to habituate” (85). Here, agency returns as embodied response.

This sense of habit as embodied knowledge resonates with how we respond to iconic images. The media capacities of Web 2.0 enable some images to become instantly iconic as they circulate widely and are repeated so often that a minimal graphic trace jogs cultural memory. Think of the many memorable photographs of contemporary protests, often transcribed within hours into artistic inscriptions (a woman standing tall against riot police, a bleeding face, a kneeling form). Iconic images rapidly become implicit knowledge; as cultural mnemonics, they are also always collectively owned. In Chun’s terms, the iconic image passes into implicit memory as embodied cultural knowledge. Distinguishing implicit from explicit memory, Chun follows Eric R. Kandel’s In Search of Memory: The Emergence of a New Science of the Mind (2007) in her elaboration of habit. Explicit memory is long-term memory housed in the brain. By contrast, habits arise from implicit memory: they are a form of knowing without knowing. We are not conscious of inherent conditioning through habituation; there aren’t any memories stored that can be retrieved. Rather, habituation reconfigures and reinforces past goals/selves/experiences in acts of constant care that look not to the past (what must be preserved) but to the future (what enables survival). As artifactual graphic signs naturalized through habituation, iconic images reside in implicit memory: hence, these culturally known signs elicit habitual responses, sometimes with great affective force.

The Kurdi image triggered responses internal to social media users because of a collective habituation to images of injured children. Historically, distress, alarm, and horror at photographs of injured children as the exemplary victims of wars, famines, and genocides have provoked controversy. Injured children, then, are embodied cultural knowledge—so embedded that it does not appear as knowledge at all. Within icon studies, such habitual response underscores the specific materiality of iconic images: these are signs which have abductive agency, capturing an immediate sense-perception of the referent.[xxiv] So one explanation for a strong affects accumulating around the Kurdi image would suggest social media users were culturally cued to respond to this image in this way. Images of injured or dead children often function so, and this was the case even before the circulation of the Kurdi image on social media. We remember Nick Ut’s “Napalm girl” running arms outstretched or Kevin Carter’s vulture approaching a skeletal baby—these are images by which we remember wars and famines. A more universalizing explanation might return to the makeup of biological systems. Visceral responses to an injured child recall past experiences—“scars” and “remnants,” as Chun names them (Chun, 2016: 95)—that serve as points of reference for coming harm to self-organizing biological systems. Hence, the images of injured children arouse protective drives, from deep anxiety to horror. Whichever direction one pursues, it is clear that complex affects such as fear, anxiety, or sadness drive habitual responses to the mediatic traces of hurt or dead children. Instant shares and likes make images of injured children iconic indicating highly sensitized responses to noxious signals. As the iconic inscriptions circulate and are recomposed, they become expressive as reasoned cultural sentiment in public cultures. In blogs and forums, the deliberative adult subject assumes an ethical and/or parental relation to the iconic injured child. A deep sense of collective culpability begins to haunt the iconic image, whether or not that culpability is repressed or acknowledged.

These explanations, however, do not fully explain the virality of the Kurdi image. After all, as Wardle (2015) notes, there were several other photographs of child refugees that had circulated before the Kurdi image; but it was the Kurdi image that caught fire. It was the viral spread that was widely considered a “wakeup call,” “a lightbulb moment,” and an image that “shook the world”.[xxv] In part, this was an engineered viral spread amplified through specific distributive chokepoints such as the Free Syria Hub or Human Rights Watch, institutions banking on particular forms of liberal subjectivity. This presupposition of liberal YOUs (as Chun puts it) marks the kind of controlled enclosure that make social media’s sense of user empowerment mythic. Within a range of theorists preoccupied with the freedom of the internet,[xxvi] scholars of platform studies underscore the business of social media. For one, Cohen reminds us, there is money to made in the YOUs value of viral campaigns; there are companies in the business of designing viral memes. Operating within the logic of populational aggregates, social media users inhabit a contorted form of group life, argues Cohen, partly as population and partly as affective publics (Cohen, 2017: 80). The YOUs entertain illusions of freedom within controlled market enclosures. They inhabit the singular drive to inhabit a plural YOU or the lonely drive to be never alone. Following these insights, the Free Syria Hub and Human Rights Watch banked on populational aggregates, a liberal YOUs value that yielded dividends. A stark picture emerges: if the YOUs in aggregated form show up in each other’s feed, does this not imply that social media is deeply segregated? Doesn’t social media proliferate “poorly gated virtual communities”? The YOUs friend, like, follow, recommend, and share with others like them. Chun(2017) names these social enclosures a prevalent homophily, a concept arising from urban segregation in the 1950s. In short, this is a group form that harvests the strengthening of already existing ties.[xxvii] Neves (2020) reads Chun’s elaboration of homophilic sociality as inhabiting the social risk of segregation: in the burgeoning hate/love groups, indeed social media platforms are rife with such gated communities. Engineered viral spreads emerge from the anticipation and management of homophilic responses. These are all the reasons why, contra empowerment, social media is widely regarded as politically defunct: anti-social, socially risky, and manipulative.

And yet, engineered spreads do not account for unanticipated viral events, for the peaking intensities of the Kurdi image. If images of injured children of the European refugee crisis had been circulating already; if institutions such as Emergency Watch had been calling for action for months, then why did this image go viral? It would be difficult to point to a single reason—that this photograph was more poetically expressive than others, or that those distributive chokepoints were particularly well coordinated. One can make a reasoned argument, though, that the viral spread was the upshot of accumulating affects around the migrant influx. Since affects are not emotions—we cannot find them in recognizable cultural forms—but energetic forces, we can only retroactively read their presence back into outbursts and peaks as accumulated intensities. Affects are also unmannerly; their eddies and flows are impossible to track in linear causalities. In this case, the migrant crisis had been unfolding for nine months. Speculations on the impact of the migrant influx on neighborhoods and cities, jobs and resources, had been ongoing across Europe. No doubt these concerns had produced unsettling affects. Reading this viral event as a tipping point for accumulating affects suggests that unconnected YOUs were already aware, affectively if not consciously, of the refugee wave. They had felt the numbers pouring into Europe. Now the task was to count those who sought refuge as Europe.

In the Twitter storm, the YOUs entered the fray as uninvited partakers banking on the connectivity of Web 2.0. Of course, the YOUs banked on established social networks and their attendant reciprocities. But they also bet on the originary multiplicity of the internet where there is little certainty of reciprocity. Chun characterizes this mode of making of ties, of entertaining non-reciprocal relations, as heterophily from which arises the monstrous chimera YOUs (Chun, 2017). To inhabit this chimera risks exposure to network vulnerabilities; moreover, the outcomes are often undecidable, without sureties. The undecidability raises allegations of the “thin politics” of social media. The collective “we” is too transient, too wavering; it tends towards an inoperative collectivity. There are no strong compositions of a political collectivity of the kind we ascribe to populism, no attempt to represent a totality of social interests. This is an affective public without common features, sometimes without shared agendas; but it is equally a group form that embraces publicness. In unanticipated viral events, such affective publics enact an “improper politics” that dissents from business as usual.

III. An Improper Politics

Following Rancière’s model of dissensus, we can read the peaking intensities around the Kurdi image retroactively as demotic projection in which a relation emerges between the collective “we” that confronts the coming “they” (encapsulated in the figure of Kurdi). The “they,” argues Rancière, is precisely the trace of the unenclosed totality that is the demos, which is never fully legible let alone quantifiable. But how do we understand the collective “we” at work in the viral spread? Essays in the VSML dossier tracking trajectory of peaking intensities offer some answers.[xxviii] They track the first tweets as emerging from Turkey, and shortly thereafter from West Asia, before entering European and North American Twitter feeds. The visualizations tell us there were European social media users for whom the highly mediatized crisis was on their shores and at their borders. Equally present were social media users at Europe’s edge, intimately connected with Europe’s migration policy because of intertwined regional histories. The intensities among Turkish social media users arose not only because of the incident’s location in Bodrum, but also as a response to the concerted European effort to make Turkey a triage center for the flow of Syrian refugees. These distinctions complicate the “we” that approached the “they” as refugees-migrants.[xxix] Beyond Europe, it is not a stretch to argue that the problem of a demos that exceeds the rights-bearing “people,” a demos that is invisible within and at the border, is now a global concern. In other words, the Syrian refugee crisis was about international negotiation of quotas and a strongly felt political dilemma resonant across national and regional contexts. Hence the European incitement to refugee incorporation hit a collective nerve. Rather than specific ideological locations, the visualizations reveal ricocheting affects—mostly apparent in hashtags—around a specific problem of an ever-expanding, always-coming demos.

The micro-actions constitutive of the Twitter storm seek to make sensible the once-invisible “part” of the demos. That uncounted surplus exceeding political representation is not as yet incorporated; it does not fit within proper political compositions. This is evident in the makeshift artisanal memes and hashtags that followed the likes and shares of the Twitter storm. Such artisanal compositions, argues Rancière, oppose quantitative transcriptions of refugees as populational aggregates. The police function of the state enacts such quantitative capture. It counts the rich, the poor, the women, the illegal immigrants. And yet, there is always a part not as yet legible, a part that keeps coming. Political activities antithetical to the police function reconfigure that which is partitioned away: “The essential work of politics is the configuration of its own space. It is to make the world of its subjects and its operations seen. The essence of politics is the manifestation of dissensus as the presence of two worlds in one” (Rancière, 2010: 37). The Kurdi image brings into the sensible “another world” of difficult and deadly crossings—the world of quotas and camps—a world that the police function of states struggles to regulate and contain. In this way, the circulating image dissents from policed partitions of the sensible. It exposes the gap: through it there is the demos, always coming, always virtual.

In this account of sensible politics, Rancière highlights the participation of “part-takers” who, as Davide Panagia argues in Rancière’s Sentiments (2015), undertake activities that might not belong to them, regardless about whether that activity is persuasive to others (Panagia, 2018: xi). They are less invested in reasoned political judgement; they just want to partake (partager or share). As I have suggested, such partaking is highly regulated through algorithmic controls of reciprocal ties on Web 2.0. But there are occasions when the partaking is excessive, leaking beyond established reciprocities. On these occasions, social media users retweet without a clear sense of how their sendings will be received. This is a drive to feel rather than count the number of likes and shares. The temporal intensity of unprecedented viral spreads suggests that the micro-actions that constitute the spread are not merely calculative.

I have argued that the sensible infrastructure of Web 2.0 makes possible the distributed affective politics of the popular. I have further suggested that, in the case of unanticipated viral events, we can read accumulated affects as traces of affective publics. If we re-embed the Twitter storm back into the public culture that consequently emerged around this iconic image, then it is clear that there was very little agreement on how the uncounted part fits the body politic—be that the nation-state or the European Union. The VSML dossier collates a spectrum of opinions on how to proceed with the matter after the Twitter storm. The spectrum unfolds an important difference between popular mobilization and populism. It is a distinction that eschews characterizing all popular mobilizations as necessarily virulent, self-aggrandizing enclosures of “us” against “them.” To think this way is a refusal to cede the ground of affective politics to populisms that espouse segregated homophily or likeness as the basis of sociality.

My way forward into this difference is to think with Edward Said’s (1983) distinction between filiation and affiliation. Filiation is affinity based on bloodlines and kinship, race and heritage, while affiliation is based on holding-in-common across difference. Filiative politics works through unifying symbols and naturalizes them into durable fetishes. What is important is that filiation does not trade in anonymity. Filiative action reveals origin, and often but not exclusively, racial origins. A fullness of identity—whether or not verifiable—is central to such populism, which dissents from the police function on the basis of historical injury. America was always white, so the filiative logic goes, or India, always Hindu. The uncounted demos is a part that once counted, that once occupied the seat of political power, but is now dethroned and runs the risk of illegibility. Such affective publics seek restoration as the true demos. In contrast, an affiliative politics trades in anonymity. There are names and titles and professions in petitions and blogs, of course. But anonymity—the impersonal experience that Rancière points to—lies in speaking with the part that is not counted: consider the Buddhists, Jains, Parsis, Sikhs, and Hindus standing against a piece of anti-Muslim legislation seeking to engineer a Hindu majority. It is a popular front mobilizing against authoritarian populism, spontaneous and leaderless. In other words, filiation relies on origin, placing, counting; and affiliation on the new, the uncounted, and the displaced. While both perform a politics of dissent, filiation remains enamored of the police function: all must be accounted for in this political space, everything surveyed and in its place. It is Europe against the refugee hordes, splintering into ever more cohesive wholes. No supplements, no entry. What crosses the partition of the sensible is precisely what must be kept at bay. Borders close; barbed wire will not be crossed.

Typically, media populism invokes a filiative politics of dissent. Habituated filiative political activities on social media foment violence against the other. The affects are so strong that no algorithmic controls seem adequate to the task of regulation. The drive for affective connectivity ensures continuing leakiness. It is against such populism that a space of affiliation arises: we glimpse a collective “we,” a loose horizontal formation of different, often heterogenous constituents. They come together around the part to which they might not necessarily belong. Those with access to digital media are often aware of their access as a privilege not available to all; the drive to quantify is a willed use of media capacities to highlight the part that does not have access. Because affiliation bonds with the surplus and recognizes it as such, recognizes it cannot be fully counted, the relationship is necessarily beyond the personal: the part of the part will always remain unknowable, anonymous. Whether or not social media users disclose their identity what they disclose about the part that they seek to make visible is that it is fundamentally different. We see such disclosures in solidarities and alliances, in happenings and rebellions, across the world, which often incite filiative backlash (from radical militias to goons employed by authoritarian masters).

And yet the springs and occupys keep coming. An improper politics, the inarticulate popular surfaces in the time-honored spaces of streets and parks and the newly durable spaces of social media. It may coalesce around avowedly local matters, but its claims as demos are universal. For better or for worse, it is the new common sense.

Notes

[i]. We are familiar today with hybrid social movements, where social media platforms are key interfaces to the street: theorists from Judith Butler (in “Bodies in Alliance and the Politics of the Street,” 2011, https://transversal.at/transversal/1011/butler/en) to Zeynep Tufecki have spoken to the affordances and constraints of this interface.

[ii]. The paper was written for the Media Populism workshop hosted by the Global Emergent Media Lab (GEM) at Concordia University, April 2018. The conveners made an important distinction between “populist media” as assimilation of tropes, sentiment, and forms to different media and “media populism” that refers to the role played by media in the creation, distribution, and promotion of the political style known as populism. The latter provocation is the starting point for this essay. I’m grateful to Joshua Neves, Giuseppe Fidotta, and Joaquin Serpe for their invitation to develop the paper for the special issue, as indeed to the workshop participants who provided initial feedback.

[iii]. See, for instance, the collection, Megan McLagan and Yates McKee eds., Sensible Politics: The Visual Culture of Non-Governmental Activism (MIT Press, 2012) as well as works like Deborah Gould’s Moving Politics: Emotion and ACT UP’s Fight Against AIDS (University of Chicago Press, 2009), among others, that theorize the affective turn in public culture.

[iv]. See, for instance, Marc Steinberg’s “The Genesis of the Platform Concept,” Asiascape: Digital Asia 4 (2017): 184-208; Tarleton Gillespie’s “The Politics of “Platforms, New Media & Society, 12.3 (2010); 347-364; and Jean-Christophe Plantin et al, “Infrastructure Studies Meet Platform Studies in the Age of Google and Facebook,” New Media & Society, 2016, 1-18.

[v]. See, Katherine Hayles, The Unthought: The Power of the Cognitive NonConscious (University of Chicago Press, 2017) and Tony D. Simpson, Virality: Contagion in the Age of Networks (University of Minnesota, 2012).

[vi]. Michel Foucault, “The Subject and Power,” Critical Inquiry 8.4 (Summer 1982): 221.

[vii]. See Michael Warner’s distinction of the 18th century male propertied public from the embodied counter-publics of the period for one notable elaboration of publics (Publics and Counterpublics, Zone Books, 2002). A complementary conception of publicness arises in the notion of “public culture” as a zone of contestation involving civil and uncivil action, a concept formative to the journal of the same title.

[viii]. David Graeber, Revolutions in Reverse: Essays on Politics, Violence, Art, and the Imagination (Minor Compositions, 2011).

[ix]. In Global Icons: Apertures to the Popular (Duke University Press, 2011), I have tracked Antonio Gramsci’s legacy in both Ernesto Laclau (On Populist Reason [Verso, 2005]) and Ranajit Guha’s (The Elementary Aspects of Peasant Insurgency [Oxford University Press, 1983]) notes on pre-political organization of the “people.” The literature on unruly mobs and crowds is too vast to cite here, but for this essay, two inspirations are Partha Chatterjee’s The Politics of the Governed: Reflections on Popular Politics in Most of the World (Columbia University Press, 2004) and Dilip Gaonkar’s “After the Fictions: Notes on the Phenomenology of the Multitude,” e-flux 58 (October 2014): https://www.e-flux.com/journal/58/61187/after-the-fictions-notes-towards-a-phenomenology-of-the-multitude/; see also, Gaonkar, “Demos Noir: Riot After Riot,” in Nights of the Dispossessed:Riots Unbound, ed. Natasha Ginwala, Gal Kirn, and Niloufar Tajeri (forthcoming Columbia University Press, 2020).

[x]. Ranajit Guha has notably traced these different media forms—drumbeats to the exchange of bread—as forms of transmission that communicate collective resistance against colonial government. His provocations inspired the postcolonial scholars to track technologies of communication beyond print media that transmit political affects.

[xi]. Bhaskar Chakravorti, “What can a government with a need to repress do in an era of equally irrepressible internet? Indian Express, Jan 11, 2020: https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/citizenship-amendment-act-caa-protests-internet-shutdown-digital-india-6210492/. Retrieved January 14, 2020.

[xii]. The name was corrected to “Alan Kurdi” later in the news cycle, so I use this version in my article. See, the Visual Social Media Lab, University of Sheffield’s dossier on the Kurdi Image (http://visualsocialmedialab.org/projects/the-iconic-image-on-social-media): Vis, F., & Goriunova, O, Eds., The Iconic Image on Social Media: A Rapid Research Response to the Death of Aylan Kurdi, (December 2015).

[xiii]. In the VSML dossier, Lucy Mayblin (“Politics, Publics, and Aylan Kurdi”) remarks that David Cameron, for one, offered to take 20,000 from camps in Syria but not Europe, a move that was soon undercut with a bill that restricted resources allocated for refugees (pitched by the then-Home Secretary, Theresa May). See also, essays by Anne Burns and Claire Wardle.

[xiv]. As two-thirds of the attackers turned out to be asylum-seekers, debates broke out over whether or not the category refugee included the asylum-seeker. When the German right-wing got in on the action and sold merchandise with the slogan “Rapefugees not Welcome,” the leader of a premiere group was accused of sedition.

[xv]. All data visualizations posted in VSML are licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND): see details for this license, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/.

[xvi]. The VSML dossier distinguishes the visualized Twitter storm from the counter-speech that followed the circulation of the images as two different moments in the life of the iconic image.

[xvii]. “Aylan Kurdi: drowned in a sea of pictures,” VPRO broadcast, 2016, see, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VcliHwsf8jI.

[xviii]. At other times, platforms have sold data to governments that have led to arrests and deportations: the infamous case is Yahoo selling data on the poet, Shi Tao, to the Chinese government that led to the activist’s 10-year imprisonment.

[xix]. Think of the controversies over Nick Ut’s photograph Phan Thi Kum Phuc in 1972 (better known as “the Napalm girl”) or Kevin Carter’s 1993 “Starving Child and Vulture” shot in famine-stricken South Sudan. Nick Ut took pains to explain that, after the photograph, he stopped his van to carry the burning children to the hospital; while Kevin Carter protested that he was not waiting for the vulture to descend on the child but had been instructed not to touch the children. In the fallout over the controversy, Carter committed suicide within a year of snapping the photograph.

[xx]. Zeynep Deyrim Gursel, Image Brokers: Visualizing World News in the Age of Digital Circulation (University of California Press, 2016). Gursel traces the multiple agencies “broker” a news photo before it makes the news.

[xxi]. Brian Massumi, Parables of the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation (Duke University Press, 2002).

[xxii]. Updating to Remain the Same: Habitual New Media (2016) is the last in Chun’s trilogy that includes Control and Freedom: Power and Paranoia in the Age of Fiber Optics (2006) on how a technology of control was managed and sold as freedom and Programmed Visions: Software and Memory (2011) on computers as the tools for negotiating an increasingly complex world.

[xxiii]. See, for instance, Lauren Berlant’s Cruel Optimism (Duke 2011) and Elizabeth Povinelli’s Economies of Abandonment: Social Belonging and Endurance in Late Liberalism (2011).

[xxiv]. This is Charles Pierce’s reading of the icon, a sign which is based on qualitative likeness to its reference. To encounter the icon, we do not use inductive or deductive reasoning. Rather, the icon triggers a sense perception of the real, an embodied response—it abducts reason. See further elaboration in Global Icons (2011).

[xxv]. Anne Burns, “Discussion and Action: Political and Personal Responses to the Aylan Kurdi Images” (VSML 2015).

[xxvi]. Most notably Tiziana Terranova, Network Culture. Politics for the Information Age (Pluto Press, 2004) and Alexander Galloway, The Exploit (University of Minnesota, 2007).

[xxvii]. See, Wendy Chun, “Virtual Segregation Narrows Our Real-Life Relationships,” Wired (April 13, 2017): https://www.wired.co.uk/article/virtual-segregation-narrows-our-real-life-relationships.

[xxviii]. 48% of the hundred most shared images were located in Europe (25% in Northern Europe, 24% in the U.K., 15% in Western and 5% in Eastern Europe) and 28% in North America. Both language capacities and the number of Twitter users in particular regions (4 million in Germany, for instance, as opposed to 15 million in the U.K.) had much to do with assessing the contours of the spread.

[xxix]. I would add that, in the global event, there were social media users that engaged the “refugee crisis” as a distinctly “European problem,” and not directly relevant to their lives; but, even here, one may think of proximate remoteness of different kinds. For instance, Californians or Texans living in the borderlands may have had greater investments in the politics of incorporating migrants into the body politic.

References

Anand, N., Gupta, A., and Appel, H. (eds.) (2018). The Promise of Infrastructure. Durham: Duke University Press.

Burns, A. (2015). “Discussion and Action: Political and Personal Responses to the Aylan Kurdi Images,” The Iconic Image in Social Media, 38-39.

Butler, J. (2011). “Bodies in Alliance and the Politics of the Street.” Transversal Texts. https://transversal.at/transversal/1011/butler/en

Chakravorti, B. (2020). “What can a government with a need to repress do in an era of equally irrepressible internet ” Indian Express (Jan 11). https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/citizenship-amendment-act-caa-protests-internet-shutdown-digital-india-6210492/

Chatterjee, P. (2004). The Politics of the Governed: Reflections on Popular Politics in Most of the World. New York: Columbia University Press.

Chun, W. (2016). Updating to Remain the Same: Habitual New Media. Cambridge: MIT Press.

—. (2017). “Virtual Segregation Narrows Our Real-Life Relationships,” Wired (April 13). https://www.wired.co.uk/article/virtual-segregation-narrows-our-real-life-relationships

Foucault, M. (1982). “The Subject and Power,” Critical Inquiry vol. 8, no. 4. (Summer): 221.

Galloway, A. & E. Thacker. (2007). The Exploit: A Theory of Networks. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Gaonkar, D. (2014). “After the Fictions: Notes on the Phenomenology1 of the Multitude,” e-flux no. 58 (October). https://www.e-flux.com/journal/58/61187/after-the-fictions-notes-towards-a-phenomenology-of-the-multitude/

Ghosh, B. (2011). Global Icons: Apertures to the Popular. Durham: Duke University Press.

Gillespie, T. (2010). “The Politics of Platforms,” New Media & Society vol. 12, no. 3: 347-364.

Graeber, D. (2011). Revolutions in Reverse: Essays on Politics, Violence, Art, and the Imagination. New York: Minor Compositions.

Gursel, Z.D. (2016). Image Brokers: Visualizing World News in the Age of Digital Circulation. California: University of California Press.

Hayles, K. (2017). The Unthought: The Power of the Cognitive Non-Conscious. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Massumi, B. (2002). Parables of the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation. Durham: Duke University Press.

Mayblin, L. (2015). “Politics, Publics, and Aylan Kurdi,” in The Iconic Image on Social Media: A Rapid Research Response to the Death of Aylan Kurdi. Vis, F. & Goriunova, O. (eds.). Visual Social MediaLab. 42-43.

McLagan, M. & McKee Y. (eds.) (2012). Sensible Politics: The Visual Culture of Non-Governmental Activism. Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Neves, J. (2019). “The (Social) Media Question: Speculations on Risk Media Society,” in The Routledge Companion to Media and Risk. Ghosh, B. and B. Sarkar. (eds.). Routledge. 347-361.

Panagia, D. (2018). Rancière’s Sentiments. Durham: Duke University Press.

Plantin, J. et al. (2016). “Infrastructure Studies Meet Platform Studies in the Age of Google and Facebook,” New Media & Society, vol. 20, no. 1: 293-310.

Probitz, Lin. (2015) “The Strength of Weak Commitment” in The Iconic Image on Social Media: A Rapid Research Response to the Death of Aylan Kurdi. Vis, F. & Goriunova, O. (eds.). Visual Social MediaLab. 40-42.

Rancière, J. (2010). Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics. London: Bloomsbury.

Said, E. (1983). The World, the Text, the Critic. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Simpson, Tony D. (2012). Virality: Contagion in the Age of Networks. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota.

Steinberg, M. (2017). “The Genesis of the Platform Concept,” Asiascape: Digital Asia vol. 4: 184-208.

Terranova, T. (2004). Network Culture. Politics for the Information Age. London: Pluto Press.

Tufecki, Z. (2017). Twitter and Teargas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protests. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Vis, F. & Goriunova, O. (eds.) (2015). The Iconic Image on Social Media: A Rapid Research Response to the Death of Aylan Kurdi. Visual Social Media Lab. http://visualsocialmedialab.org/projects/the-iconic-image-on-social-media