Vol 23 Publishing After Progress

Open Peer Review of

Committing to decolonial feminist practices of reuse

Priya Rajasekar

University of Cambridge

The article ‘Committing to decolonial feminist practices of reuse’ is an effective critique of contemporary principles and practice of open access calling into question the overemphasis on governance of knowledge objects while preserving the notion of the individual author as natural owner vested with ultimate authority to determine rules of access and engagement. Highlighting the limitations of licencing mechanisms that continue to operate in liberal humanist ways, the authors revisit open access methodologies through the lens of feminist and decolonial thinking as a way to expand the possibilities for a more ‘relational, intersectional and decolonial’ engagement.

Reviewing diverse and innovative OA licencing approaches, including those that seek to embed decolonial and indigenous methodologies, the authors contend that licencing through continued exclusion and discrimination in various ways continues to fall short of its implicit promise to deliver freedom of access to knowledge objects. The article concludes with a discussion on the authors’ ongoing experimentation with Collective Conditions for Reuse that steers away from the limitations of licencing practices gesturing instead towards a prompt or invitation that nurtures more responsible encounters. Drawing from Miriam Aouragh’s notion of ‘radical kinship’ the authors propose that such a feminist and decolonial engagement could pave way for a more thoughtful, situated and relational encounter with knowledge production practices that remain attentive to embedded power relations and considerate to the consequences of such engagement.

As a situated encounter, the refreshing promise of moving past ‘licencing’ of knowledge was an invitation to engage more freely with the article. The persistent guilt of trespassing that accompanies any use of licenced material was replaced with a responsibility to contribute purposefully drawing on my situatedness so potentially improved conditions for reuse may emerge through further reflection and deconstruction.

The article’s positioning of feminist and decolonial methodologies (even if the former seeks to learn from the latter) left me wondering if the separation implied that some non-western feminisms were excluded from the feminist methodologies adopted by the authors. It also made me wonder if the article has missed the opportunity to further critique how western feminisms through their continued preoccupation with the white human figure are at risk of reproducing the same exclusions in their approach to knowledge principles and practice.

To elaborate, the collective conditions for reuse that the authors propose may risk being indifferent to the category of the non-white woman as Lugones, Mohanty and others have argued, and therefore overlook other emergencies and urgencies that remain the preoccupation of the marginalised subjectivities that CC4R seeks to foreground. So, even while the door remains open and inviting for engagement, the situatedness of these marginalised subjectivities may render it impossible for them to have the luxury and freedom to accept the invitation or respond to the prompts. I also wonder if it is possible for the constituents of the collective to remain unaffected through these entanglements and how under conditions of egalitarianism and attentiveness to power asymmetries, western feminist encounters with indigenous cultures may shape the relationship – with ‘people, issues, concerns, stories and histories’ and also presents and futures.

As a gentle provocation and invitation for conversation, I ask if the collective conditions for reuse which has emerged as a way to address embedded power dynamics and the preoccupation with human authorship and ownership of knowledge objects, has also the responsibility to deepen the consequences of this entanglement with decolonial and indigenous methodologies. Further, in doing so, should it be more thoughtful and considerate to think not just about freeing up the site of knowledge creation for meaningful encounters but to ask if the invitees truly have the freedom to engage. As indigenous communities around the world grapple with the existential crisis of climate change and its impact on lives, cultures and spiritual practices, should the collective ‘conditions’ for reuse also be an examination of the ‘conditions’ that continue to keep marginalised groups preoccupied with life and death. Are there more urgent and immediate needs that need attention and should the space of reuse be rearranged to accommodate this urgency? In other words, one could question whether ‘conditions’ refer to the collectively-agreed norms and responsibilities or do they refer to the ‘states’ that open up access so these invitations and prompts could be accepted. In effect, what I am saying is that for as long as the engagement with indigenous knowledges remains confined to the theoretical and methodological while excluding the ontological, the opportunity to work in disappropriative ways remains underexplored.

This nagging question centring my attention like a pebble in my shoe imbues other encounters in the space. For instance, the sustained engagement of the authors of CC4R with Open Licence practices that tend to ignore historical contexts and power asymmetries for their potential to inform positive reuse practices is encouraging. The reluctance with which authorship is acknowledged further gestures towards an intent to break free of individual appropriation of the collective endeavour of knowledge production.

Nevertheless, it leads me to ask if CC4R remains conscious of not just the historical contexts of these asymmetries but the ongoing injustices that indigenous communities and cultures are being subject to. This question extends to the point that the authors make on the use of data for open science and the need to investigate the scope of what data means within indigenous worldviews. The authors raise pertinent questions on the risks of biopiracy and biocolonialism in FAIR principles governing use of indigenous data and favour the application of indigenous approaches to feminist politics of reuse as a way to reorient the interpretation of what data means towards indigenous understandings. Once again, the potential to not just consider indigenous understanding of data but empower the embedding of such understandings in institutional (academic and beyond – IPCC, WEF etc.) seats of power seems to me an opportunity that the CC4R could begin reflect on. Is it enough for CC4R to be interested in the constituent principles of the content that is being considered for reuse which no doubt has the capacity to expand the conversation so it dwells on the questions raised here but is it also necessary to reimagine the site of reuse as dispersed and evolving collective spaces within sites of power where the purpose of reuse of this data is determined.

In this vein, I use the invitation to engage as an opportunity to expand the potential of CC4R to respond to the urgency of the present through applying indigenous knowledge notions of deep and circular time as a way to reuse knowledge so the injustices of the past are not revisited in the present and future through these relational ways of engagement where the question in not just about the ‘how’ and the ‘why’ but also the ‘what’ and the ‘when’.

Response from the authors

Femke Snelting & Eva Weinmayr

Dear Priya,

We are writing to you from Revisit Reuse, a temporary space we set up in Brussels at the beginning of May to meet with a small group of participants to work on re-formulating CC4r. The plan was to address some questions and issues that were brought up by participants, ‘prompters’ and other interlocutors, including you. The participants to this session have just left, and we are here processing your gentle provocations and questions with the lingering presence of two intense days, and 19 prompts spatialised to inform our thinking process.

In other words, one could question whether ‘conditions’ refer to the collectively-agreed norms and responsibilities or do they refer to the ‘states’ that open up access so these invitations and prompts.

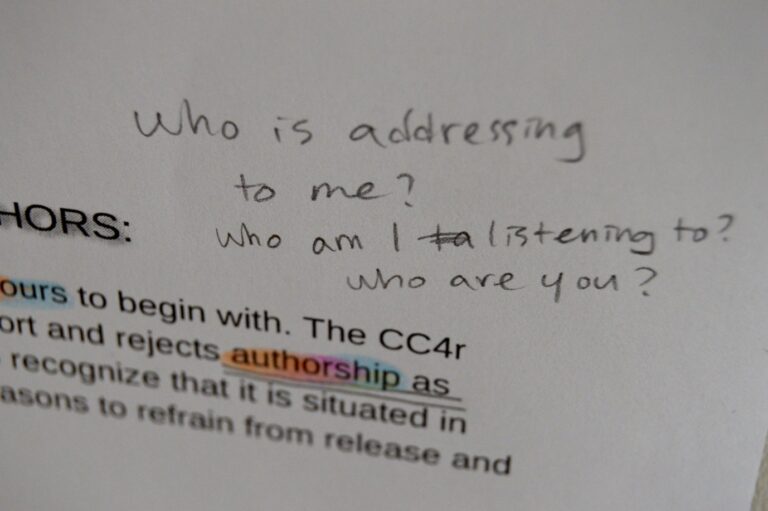

On the second morning of the two-day session, an interesting shift happened that we feel could be a beginning of a response to your question at what level CC4r can or cannot address conditions.

In an interview that Eva recorded with Femke and Elodie Mugrefyia a few years ago, Elodie explains how CC4r could signal problems and call for a change in practice. (This interview was conducted by Eva Weinmayr and Lucie Kolb in the context of ‘Teaching the Radical Catalogue – a Syllabus’, 2021) Following that intuition, we decided to rename the document from ‘Collective Conditions for Reuse’ into ‘Collective Commitment to Reuse’ because the framework of ‘conditions’ seemed to miss the point. We felt it stayed too much with a contractual understanding of what reuse can do, instead of a solidary commitment to shared decolonial knowledge practices that we are after.

This shift from conditions to commitment also meant that we could reformulate the function of CC4r into a process, rather than a legal tool, as ’a ground from where to commit to’ as Castillo, one of the participants in the work session, formulated it.

Are there more urgent and immediate needs that need attention and should the space of reuse be rearranged to accommodate this urgency?

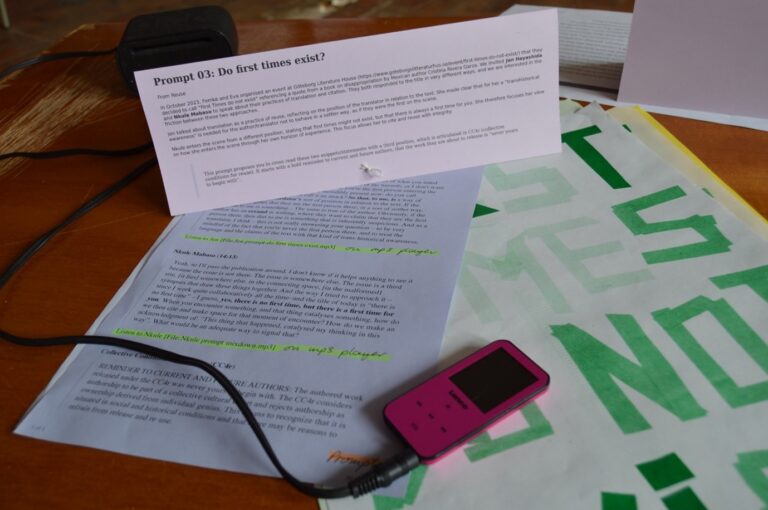

Of course, we are doing this work while our eyes are on the destruction of Rafah by the Israeli military and months into an unfolding genocide. And at times we wonder if these minute questions of authorship and ownership are worth paying attention to, they seem so futile in the face of this violence. But as we tried to articulate at the public opening evening of the work session in Brussels, the work is political in that it addresses the individualist, colonial modes that are engrained in modern copyright law. To remember that there are no first times. As Jen Hayashida explains in ‘Prompt 03: Do first times exist?’:

Obviously, if the author has an errand in writing, where they want to claim that they are the first person there, then that to me is something that is inherently suspicious. And as a translator, I think (…) to be very mindful of the fact that you’re never the first person there, and to treat the language and the claims of the text with that kind of trans-historical awareness.

The research is about how to integrate such trans-historical awareness into creative practice. How to develop other ways of making and sharing work that start from relationality rather than from the settler mentality of normalized modes of making and claiming work. And in that sense, it is speaking back directly to these urgencies.

Once again, the potential to not just consider indigenous understanding of data but empower the embedding of such understandings in institutional (academic and beyond – IPCC, WEF etc.) seats of power seems to me an opportunity that the CC4R could begin reflect on.

It’s been quite encouraging that since the release of CC4r in 2020, the commitment (formerly condition) has been applied to a range of publications from different fields of knowledge now circulating in academic, activist and artistic contexts. See the growing collection ‘CC4r in use’ which we started in collaboration with Constant in Brussels ranging from self-published pamphlets, a submitted PhD thesis, to an academic reader published by Bloomsbury.

So far CC4r is used within a community of practice that is loosely connected, its use and application show that there is an urgency or need to start addressing power asymmetries implicit in universalising licence practice. CC4r is of course far from being “the perfect tool” that merely needs to be applied. Rather, it asks the reuser to practice with it.

One publication in this collection, Futurology of Cooperation, for example, uses a Creative Commons licence (as a legal device) adding the CC4r including a narrative appeal that ‘open means different things in different contexts and that there might be reasons to refrain from reuse’. Also prompting the reuser to take the implications of reuse into account and to ‘be attentive to the way re-use of materials might support or oppress others, even if this will never be easy to gauge’.

This is a call to practice. While you are suggesting to enter or focus on policymaking, we made this step in order to NOT outsource responsibility to the law but to develop a practice which addresses power asymmetries on many levels.

We were deliberating a long time about CC4r not being police-able and our ongoing conversation with lawyer and legal scholar Séverine Dusollier helped to understand the agency of a non-enforceable ‘commitment’ that asks for negotiation, support and solidarity rather than giving permission from an entitled position of ‘ownership’. (Transcript of conversation with Séverine in November 2023).

I use the invitation to engage as an opportunity to expand the potential of CC4R to respond to the urgency of the present through applying indigenous knowledge notions of deep and circular time as a way to reuse knowledge so the injustices of the past are not revisited in the present and future through these relational ways of engagement where the question in not just about the ‘how’ and the ‘why’ but also the ‘what’ and the ‘when’.

One of the 19 prompts commissioned for the work session Revisit Reuse at the beginning of May was concerned with the ‘when’. As explained above, the prompts are coming from different angles, addressing potential gaps in the CC4r. One of the prompts, actually, was interested in the ‘when’.

Traditionally, in legal practice, a licence, mostly organises the use of the work once it is created. It is being attached to an object at the very end of a process. If we understand knowledge practice as process-based rather than result-based, we’d need negotiation at the beginning of the process of collaboration. This is what a protocol, agreement, or commitment does. It defines the modes of collaboration at the very beginning: you are in a dialogue. This is quite different from a licence which is more like a stamp attached at the end, when the objects start to wander off to the reader, the reuser.

As you bring up, it feels that the potential of CC4r as a commitment, would be a commitment to all aspects of knowledge practice (we are a bit blurry about what we mean by that by the way, for us creative practice is knowledge practice and vice versa), how, why, what, when and also the way these come together in trans-historical, spatio-temporal aspects of collective practice. Participants in Revisit Reuse called this the need ‘to enter sideways’ and proposed to include an exercise in CC4r that would allow us to ask questions in the beginning of a process, but maybe it is about asking questions all the time.