It is Sunday morning in Cali, the sunny Colombian city that is known as both the world’s capital of salsa dance and the former headquarters of a powerful drug cartel. Outside a tiny church that was built two centuries ago, a dressed up crowd stares at the entrance, as if waiting for a groom and bride to step out to be showered with uncooked rice. Nearby, some kids play and seem suddenly amused at the sight of something above flying towards the crowd. People from the crowd also turn their heads up and see it. The elderly seem to wonder while the younger ones seem to guess. Various options are considered, from a bird to an aero modelling plane, including a vampire and even a weapon. In fact, it is a drone hired as a gift for the occasion. You know that in order to immortalise such an important day, nowadays we need both the aerial vision and the high definition (HD) that only drones can provide.

Anthropologist Michael Taussig (2009) sees in gold and cocaine the two commodities that have most fascinated Colombia, first as a colony and then as a republic. Risking a rather heterodox interpretation of Taussig’s thesis, I would position HD alongside gold and cocaine as the quintessential fetish that currently marks Colombia’s history and political economy. Hito Steyerl wrote that ‘a high resolution image looks more brilliant and impressive, more mimetic and magic, more scary and seductive than a poor one. It is more rich [sic], so to speak’ (2009: nonpag.). At the same time, Colombian fascination with HD is comparable to that of other countries with a taste for leading technology. After all, ‘Colombia is a normal country, with problems any normal country could have’, as certified by Rudolph Giuliani in 2014 while he was visiting Bogotá for a consultancy on homeland security. During his three-day stay Giuliani recommended that Colombian president Juan Manuel Santos deploy drones equipped with artificial vision technology and HD cameras as part of a security strategy for the new ‘post-conflict’ chapter of Colombian history. In this context, the drone is not just a fascinating technology but also an emblem of the possibilities for change, a way to bring the desired future to the present. Colombia is not quite there yet, but the drones will help it to arrive safely.

Only a few months after Giuliani went to Bogotá, the Colombian football team took part in the World Cup hosted by Brazil. The players found themselves being recorded by drones up until the day when they had to leave the competition. Knowing this, they made quite a spectacle in order to communicate to their fans – not just the Colombians – that they had a real chance to win the Cup. Every time a goal was scored, every time a rival was beaten, the players danced enthusiastically to a tune that became, temporarily, a sort of unofficial national anthem. Ras tas tas, performed by a band from Cali, is an urban variation of a salsa tune called Salsa Choke. The only expression from the lyrics that would be intelligible for the non-Spanish speaker, and that is repeated constantly throughout the tune is ‘full HD’. Ras tas tas has popularized the use of ‘full HD’ as an adjective that can be applied to anything brilliant, excellent or ‘top’, anything from clothes to even a person. Being ‘full HD’ in Colombia is an object of desire that exceeds the realms of the visual. It is a status, a social capital to acquire that permeates various layers and conditions of society and that can be expressed in a number of ways, from purchasing the best, latest, and biggest HD television set to having your wedding recorded by a drone.

Wait a minute: did someone in the wedding crowd really say ‘vampire’? The relationship between Cali’s tropical environment and those creatures from the Carpathians may not be as arbitrary as it seems. Not only because in fact Cali has a climate that is ideal for bats, nor because we could use vampires as a metaphor of Cali’s bloodsucking mosquitoes. More deeply, the social and cultural history of Cali is closely connected to vampires, and this connection had been recorded long before the drones arrived. Locals and foreigners have extensively recorded Cali for fiction and non-fiction films since the beginning of cinema in Colombia. In its long filmic tradition this area has had the privilege of generating the first images ever shot in Colombia, the first silent movie, the first pictures in colour and the first films with sound. In the eighties, Cali-based filmmakers Carlos Mayolo and Luis Ospina recorded a series of films that recovered local myths and legends that belonged to rural cosmogony as parables of power to explain the social and political situation that people were living in the area. This experiment was later known as ‘Tropical Goth’ (Flórez, 2015), and it showcases Cali’s longstanding fascination with vampires, demons and other evil forces.

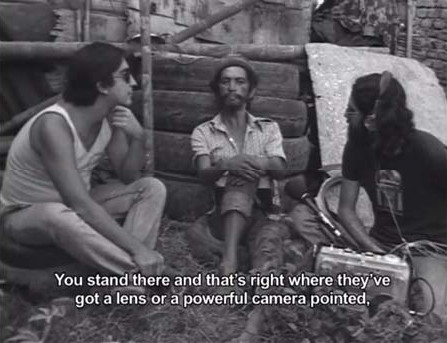

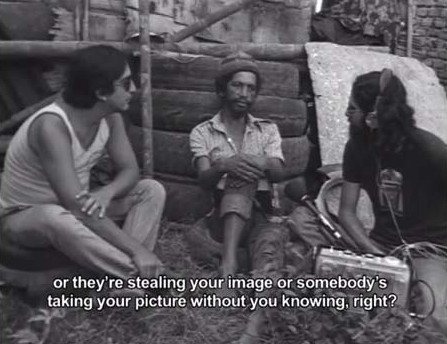

Luis Ospina’s Pura sangre (1982) retrieves an urban legend about a feudal landlord armed with hypodermic needles who sucked the blood of Cali’s teenagers in a sugarcane plantation. Agarrando pueblo (1977) (translated as Vampires of Poverty) is a fake documentary depicting two filmmakers that follow people on the streets, in order to set up scenes that resemble poverty. The film is a satire of a very specific situation, one in which Colombia was being exploited by being broadcasted. Such an exploitation fed the world not with the blood of Colombians but with images of their misery. If, at this point, the relation between vampires and drones has not yet surfaced before the reader, let us draw upon one last resource: the media. Regional newspapers are currently announcing that Cali will deploy drones (as part of a pilot program starting June 2015) in order to carry blood samples between hospitals and to remote areas. The unmanned aerial vehicles will fly over the sky of the city equipped with high definition cameras and loaded with the blood of the valley’s inhabitants. Jokes about vampires have spread quickly in the streets.

In one particular shot of Godard’s La Chinoise (1967), one can read ‘vague ideas with clear images’ on the wall of a set. One can also see that the text continues off-screen. That partial take is the one I borrow for this story about drones and vampires. The images in this story are ‘clear’ both because of HD and because the sun in Cali is perennial. The ideas are vague because drones, like vampires, play subtle tricks upon human understanding. The same cutting-edge device that promises ‘development’ and progress, wealth and ‘post-conflict’ security, resuscitates awareness about the vampires in Colombian history, a phenomenon that has been powerfully addressed by the longstanding tradition of Cali’s cinema.

References

Eljaiek, G. A. (2012) ‘Transilvania-Cali-Bogotá: Tropicalización’ in Tres películas de horror colombianas. Aproximaciones al cine de terror en Latinoamérica y el Caribe. San Juan: Isla Negra Editores.

Flórez, E. (2015) ‘I put a spell on space: Torrid-Zone Myths and Economy’, Terremoto (March 23).

Martín, A. (2010) ‘Cali, ciudad de cine: entrevista a Luis Ospina’, Karpa 3.1. Available at: http://web.calstatela.edu/misc/karpa/Karpa3.1/Site%20Folder/luisospina.html

Taussig, M. (2009) My Cocaine Museum. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Steyerl, H. (2009) ‘In Defense of the Poor Image’, E-Flux Journal 10 (December). Available at: http://www.e-flux.com/journal/in-defense-of-the-poor-image

El Tiempo Cali (2015) ‘Drones serán usados en Cali para trasladar muestras médicas’. Available at: http://www.eltiempo.com/colombia/cali/drones-usados-para-trasladar-muestras-medicas-en-cali/15634995

Minuto 30 (2014) ‘Giuliani recomienda a Colombia drones y nuevas tecnologías contra el crimen’. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b5N6f3w_V1I/

VariosVideos (2014) ‘Colombian Football Team Dancing Ras Tas Tas in 2014’. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=52OwuCccEws/