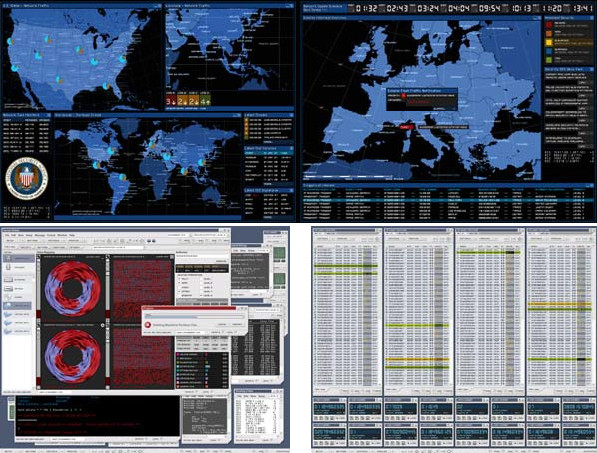

Drone conflict is carried out by combatants facing a bank of screens and operating an array of controls in a place that is separate from the heat of battle. The place from which drones are controlled, the control room, has a history that pre-dates drones. The spatial arrangement of screens, controls and humans that we are familiar with from images such as Fig.1 has been taking shape over the course of more than a century of mechanization and automation. The airmens’ uniforms attest that this is a military environment, but the lines of development that have led to the contemporary control room are not exclusively military. What we see today has become possible due to a general adoption of technological tendencies – virtualization, remote control, simulation, real-time processing, networked computing, graphical user interfaces – across many fields of activity. The transformation of the theatre of war into the virtual, audiovisual, theatrical experience of the drone control room is part of a broader, deeper transformation of modern experience itself, including politics, under the sway of technoscientific media. The history of the control room that I present here draws on seemingly separate sources that are in fact interwoven: a sampling of the Hollywood control room since 1971 and developments in engineering and technology, with an emphasis on military contexts. As a key site for the management of modernity in all its complexity, the control room is an instance of the ‘organization complex’, Reinhold Martin’s term (2005: 3-4) for the techno-aesthetic wing of the military-industrial complex.

It would be simplistic to enumerate control rooms as they appear in screen fictions and to set them side by side with what ‘really’ goes on in power stations, surveillance networks, space mission controls and, in the drone context, the Ground Control Stations from which missions over Iraq, Afghanistan, Ukraine and Gaza are controlled. To speak merely of ‘representations’ is to miss the co-constitutive, shared materiality and history of drones, control rooms and the legal-political contexts that they create and are created by. Further, addressing the shared materiality of these media and other technologies puts a proper emphasis on specific instantiations of technology and power and thereby avoids what Benjamin Noys in this journal issue calls ‘drone metaphysics’.

The challenge is to describe how these things are co-constitutive. To do this, I am adopting a media archaeological approach as the best way of accounting for the imbrication of the material bases of law, of technology and of media that are in play in the control room. Media archaeology is a relatively new term and not strictly defined, although Erkki Huhtamo and Jussi Parikka capture several important features when they say that it ‘rummages textual, visual, and auditory archives as well as collections of artifacts, emphasizing both the discursive and the material manifestations of culture’ (2011: 3). In the following, I will connect the history of the control room in film with concomitant evolutions in computing, warfare, information theory, law, geopolitics and consumer products. When it becomes clear how the discursive and material worlds are fully enmeshed with one another, it also becomes clear that it is not possible to describe the political without understanding its aesthetics, nor to understand the legal without understanding its materiality. So, when I examine these and suggest, to borrow a phrase from Roberto Esposito (2011: 3), that their ‘phenomenology is structurally analogous’, it is not to say that they are all the same or meaningfully different. Rather, it is to say that to study one of them is also to study them all. For all these reasons, the three periods in the history of the control room that I suggest do not open or close with landmark events; rather, they are attempts to group associated tendencies in a coherent manner: 1939-1971 witnessed the gradual normalization of the control room as part of the spread of the cybernetic Weltanschauung throughout advanced military and industrial-scale projects; in the period 1971-1992, computers and control-room scenarios gradually shift towards miniaturization and domestication; while the years since 1992 present a trajectory whereby the control room itself is apparently dematerializing and the capacities of computing become more and more seductively emphasized.

The ‘archaeology’ of media archeology will of course bring to mind Foucault’s method of identifying the traces of discourse where it effaces itself as discourse. As Matthew Fuller describes it, ‘Foucault did not simply work on documents and their dynamics of composition and arrangement, but also what they refer to and invoke … and the “apparatuses,” “instrumentalities,” “techniques,” “mechanisms,” “machineries,” and so on by which they are wrought and made available’ (2005: 61). In particular, it is Foucault’s concept of apparatus, or dispositif, that best captures the configuration of architecture, information and power that is the control room: ‘a thoroughly heterogeneous ensemble consisting of discourses, institutions, architectural forms, regulatory decisions, laws, administrative measures, scientific statements, philosophical, moral and philanthropic propositions’ (1980: 194). Indeed, there are clear parallels between the cybernetically conceived control room and the prison of self-regulating inmates proposed by Jeremy Bentham, which Foucault famously analyzes (1979: 200-18).

Foucault makes it possible to think about political power in the era of governmentality in terms of techno-aesthetic form. The cinematic techno-thriller, particularly when it is concerned with counterterrorism and its enemies, displays the permanent political crisis of the state not simply narratively, but as a crisis of techno-aesthetic form. The control room is the key manifestation of this crisis. The striking preponderance of screens embedded within screens in the control rooms of these narratives is a techno-aesthetic manifestation of the spatial and logical paradoxes of emergency jurisprudence and, more broadly, of the strange location of political subjectivity in the matrix of technoculture. As we shall see, the fully dispassionate, anti-metaphysical understanding of how power works that we find in the political philosophy of, among others, Carl Schmitt and Giorgio Agamben helps us to recognize the shared materiality of law, politics and form.

1939-1971: The Birth of Remote Control

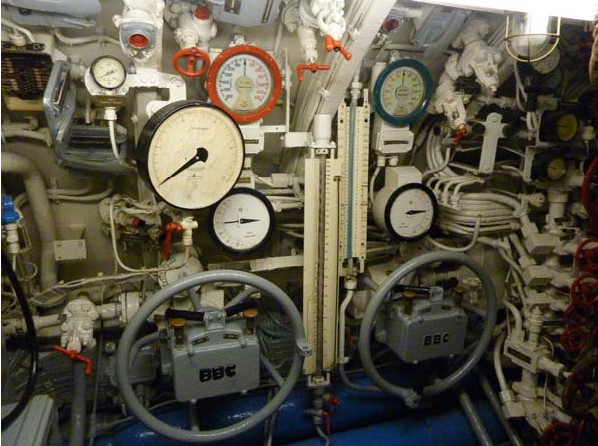

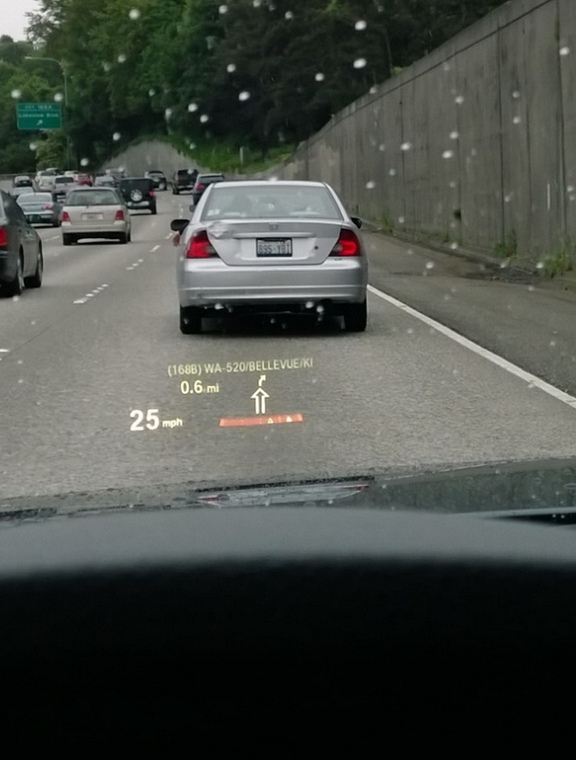

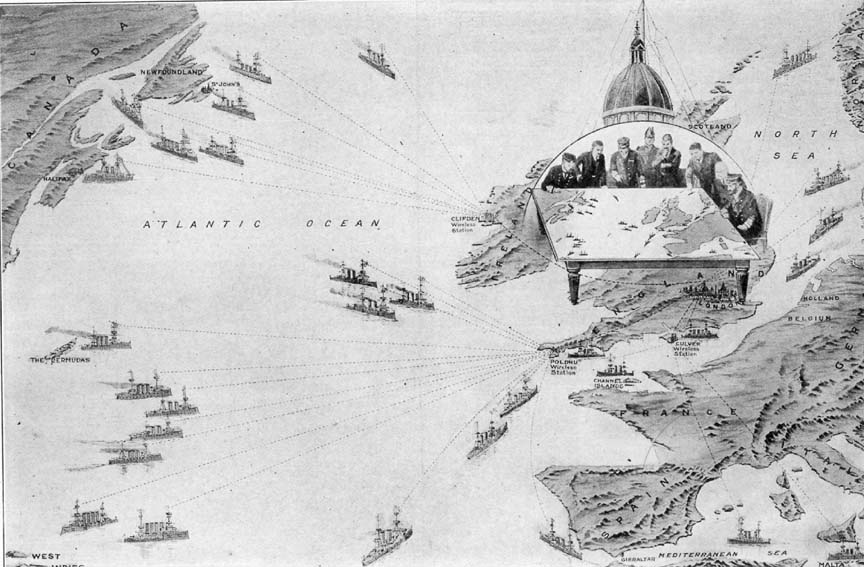

The process by which command and control took its place at the heart of modernity is as long and complex as the process by which conflict and society in general became mechanized in the course of the 20th century, and can barely be sketched here. But if we look for the first instances of what by the 1960s were known as ‘interfaces’ between humans and machines, we find them in submarines and aircraft just before World War I, and they appear in screen narratives soon after (as in Fig.2). These mark a kind of precursor to the control room in the sense that they made it possible for conflict to be fought to some degree remotely, and through the medium of a panel of instruments and indicators. The rendering of a battle space as a set of mathematical coordinates is not wholly new in this period – artillery has a long history, after all – but the coming of submarine warfare and airpower, especially from 1939, accelerates the process of what Bernard Stiegler (2014: 54-56) calls ‘grammatization’.

Grammatization is the process by which language, gestures and bodies become rendered informationally by mechanical and industrial processes. A key example for Stiegler is the capture of animal movement in prehistoric cave paintings, which is a kind of arche-cinema. The modern era, then, is when the organs of perception become, through the process of grammatization, part of a technical-social-psychic dispositif. The epitome of this dispositif is the interaction between humans and screens, in other words, the experience of cinema as well as of the control room.

There are, however, degrees of remoteness, and there is some difference between conflict as experienced by a drone operator and a fighter pilot or submariner. For the pilot, feedback comes not only as grammatized information through dials, gauges and panels, but also as weather, G-force, fire, shrapnel, injury and death. This period sees a gradual shift towards remote control, starting with the fundamental transformation of inserting an instrument panel between the human and the object being operated, and gradually replacing mechanical parts with servomechanisms. The transformation between the technology of Fig.3 and Fig.4 is described by Maurizio Morgantini in the following terms:

Who can forget the classic submarine hero of naval battles in American movies? With his T-shirt spotted with grease and his skin shining with sweat and at the order of ‘rapid immersion’, he would turn the fly-wheels, which were directly connected to the valves regulating the intake of the water: he would carry out a direct mechanical relationship with the objects. Today that very same sailor would be dealing with small levers or buttons requiring the lightest touch: between the action and the effect, various interfaces, which have become stratified, are used to amplify signals, activate servomotors, initiate autodiagnostic processes, and link an event with other surrounding events. (1984: 22)

The birth of such remote control has obvious practical consequences for social life, producing greater centralization, economies of scale, and the inculcation of values such as efficiency and profit-maximization at the expense of, say, handicraft, tradition, the commons, and egalitarian conceptions of the public good (Winner, 1986: 19-48; Heidegger, 2003; Gillespie & Alder, 1998). However, there is something deeper at stake in the ushering in of fly-by-wire technology and remote control, which changes the nature of sovereignty itself. As Giorgio Agamben shows in The Kingdom and the Glory (2011), a tension that is inherited from theology exists in the concept of sovereignty (see Väliaho, 2014 for more on the visual economy of this concept). On the one hand the sovereign is too exalted to get involved in the business of governing human affairs, and on the other, the sovereign is the one who runs the government. Arguing that our modern political categories are secularized theological categories, Agamben suggests that these poles correlate with the difference between the unchanging, eternal God who is permanently aloof, and the God who runs the government (the oikonomia in the Greek tradition and, tellingly, the dispositio in the Latin) (2011: 1-5, 40). But the tension between these poles keeps them bound together as much as it separates them. The arrival of command and control into political life, military and civilian, threatens to rupture this system.

The Nazi jurist Carl Schmitt (2004) decried the transformation of politics into technology, arguing that what we would today call affect is essential for a vital political system, and that the moral compromises of liberal democracy and its technocratic thinking are dangerously disaffecting (see also McCormick 1997). Remote control threatens to isolate the sovereign and the system of government from one another; in this light, it becomes clear why the control room screen narrative is so concerned with how executive power is undermined by the complex machines that are supposed to do its bidding.

By the 1960s, the control room had become an increasingly familiar staple in the portrayal of great technological enterprises, such as satellite television (Telstar in 1962), the space race (the moon landing of 1969, see also Fig.9) and large-scale military enterprises (the massive SAGE air-defence computer, which became operational in 1963). During the same period, the control room was a familiar site of conflict in screen narratives in several genres, for example Fail-Safe (1964, Fig.6), Dr Strangelove (1964), You Only Live Twice (1967), Billion Dollar Brain (1967), Hot Millions (1968), Colossus: the Forbin Project (1970), and the television series Star Trek (1966-69). These cinematic control rooms fit the perception that the greatest threat to security is from a nuclear-armed monolith such as the USSR, or from a space race rival such as China or SPECTRE.

In The Closed World, Paul N. Edwards describes how the post-1945 period in the US saw a combination of cybernetics, management theory and military strategy that produced a new material and metaphorical sense of closure. The typical control centre of the SAGE air defence system of the 1950s for instance, was ‘an archetypal closed-world space: enclosed and insulated, containing a world represented abstractly on a screen, rendered manageable, coherent, and rational through digital calculation and control’ (1996: 104). Edwards concludes,

Everything in the closed world becomes a system, an organized unit composed of subsystems and integrated into supersystems. These nested systems … are constituted through metaphors, technologies, and practices. The metaphors are information, communication … the technologies are computation and control; and the practices are abstraction, simulation, engineering, and panoptic management. (340-1)

These changes are also expressed architecturally, as Reinhold Martin points out. Also writing about SAGE, he observes that it ‘exemplified in both its architecture and in the logistics of its design and production the dispersed, computerized spatiality of the organizational complex as it passed through the research laboratories of universities and corporations’ (Martin 2005: 190). The control room is part of a set of interconnected windowless and secluded spaces ‘in the “deep space” of air-conditioned office buildings’ (195).

1971-1992 –The Control Room Centralized and Distributed

1971 may be chosen as a threshold year in the history of the control room, as it is when we find three striking instances that epitomize both the centralizing logic of cybernetic thinking and its tendency to form distributed networks. The two instances in film are THX 1138 and The Andromeda Strain, which I will come to shortly. The other is the Cybersyn project, an attempt to apply the principles of cybernetics to the Chilean economy under the new government of Salvador Allende. The aim of Cybersyn was to coordinate, in real time, the resources of the entire Chilean economy in a centralized way by feeding data, via an early version of the Internet, to seven economists and managers who would issue commands in response to changing situations regarding transport, weather, strikes, electricity supply and other variables – all from a control room. Pinochet’s coup d’état of 1973 marked the end of the Cybersyn project before it became fully operational, but not before its control room had been designed. Cybersyn presents us with evidence of the expansion of the imaginary of the control room from a place for conducting large-scale projects, such as the NASA Apollo Control Room in Houston, Texas, to a place from which an entire state and its economy could be run.

The displays on the walls of the Cybersyn control room are an example of the schematizing, centralized, reductive Weltanschauung of the management theory that prevailed at the time and of which Cybersyn’s guru-designer, Stafford Beer, was a noted proponent. In the secret underground biothreat facility of The Andromeda Strain, the built-in, furniture-like screens and consoles of the control room offer a similar vision of solidity and long-term planning, while the blinking array of levers, dials, display panels and buttons convey a sense that a hard-wired piece of engineering hardware is under control. The film presents a vision of technology triumphant under siege, offering a reassurance that this technology can control threats.

Of course, offering reassurance about a threat also involves substantiating it (see Massumi, 2010), and The Andromeda Strain (Fig.9) does exactly this by enacting how control can shift from human hands to technological control. In Speed and Politics, Paul Virilio describes the same problem: the technology of nuclear arsenals made traditional geostrategic conflict obsolete while making it possible to think of highly mediated conflict as entirely virtual. The ever-increasing speed of weapons and their control systems meant that the reaction times of each side in a scenario of nuclear conflict were constantly reduced; what was at stake in the Cuban Missile Crisis, according to Virilio (1986: 133-35), was the potential reduction of Washington’s reaction time to a Soviet missile attack from 15 minutes to 30 seconds. From Fail-Safe and Colossus to WALL·E (2008) to the television series 24 (2001-2014), the nightmare scenario is one in which the technology of the control room has itself taken control and reduced the human protagonists to mere spectators.

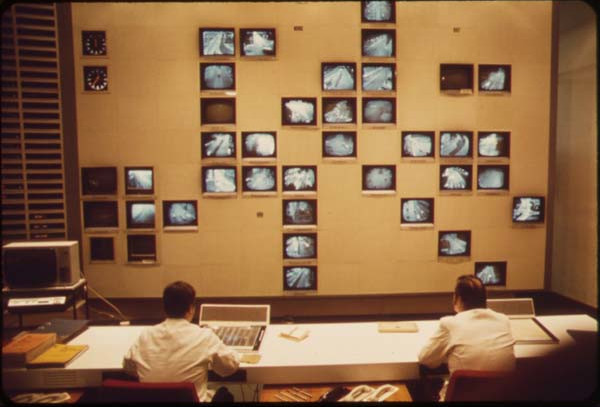

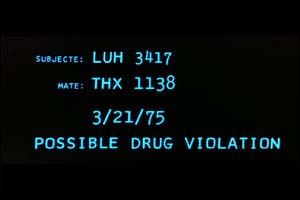

1971 is also the release year of George Lucas’ film THX-1138, which in retrospect can be regarded as a precursor not only to Lucasfilm’s Star Wars franchise, but to a whole swathe of seminal Hollywood visual effects across several genres up to the present that have been produced by the company that Lucas founded in 1975, Industrial Light & Magic. The control room screens of THX-1138 are used to monitor every aspect of those who labour in the high-tech laboratory-factories. The screens feature either the live feeds from surveillance cameras or simple text/graphical displays (fig.10). Each display screen is simply a cathode ray-tube embedded in a desk-console, and the computer-generated data are unmoving. An innovative feature in 1971 was the soundtrack’s flow of almost undifferentiated voices clouded with static interference, communicating what is frequently unintelligible data and instructions to one another in jargon-laden technospeak.

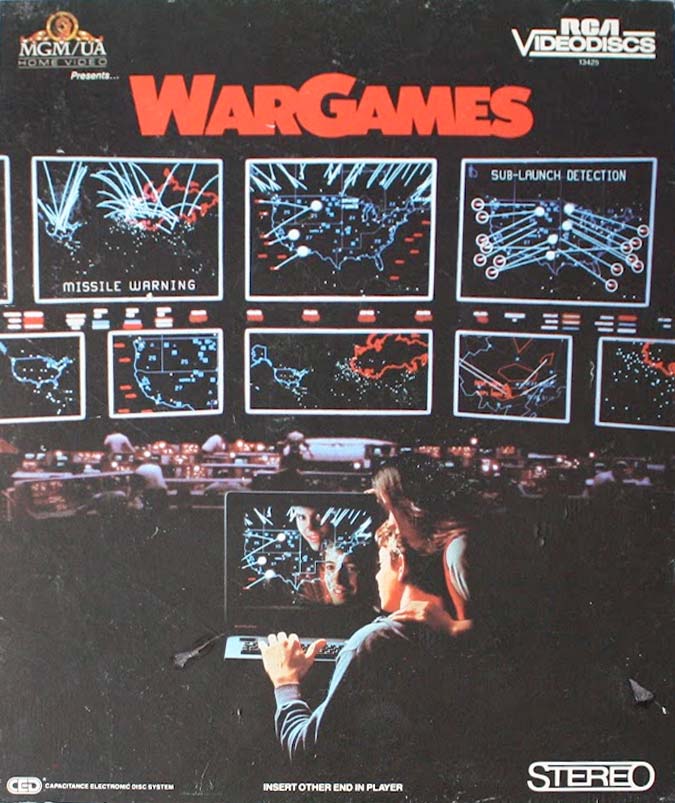

The arrival of the home computer for hobbyists in the late 1970s brought a gradual but steady decline to industrial-scale mainframes in the control room. The personal computer brought new narrative possibilities, making a film such as WarGames (1983, see Fig.11) suddenly possible, where the hub of the action is a teenage hacker (a recent concept – the OED’s first mention of this usage dates to 1976) with a computer hooked up to a telephone in his bedroom. In keeping with the times, the interface in WarGames is similar to the text-adventure type of game popular among the early hobbyists – a graphics-free, question-and-answer text interface on monochrome monitors. WarGames’ government control room, located under a remote mountain, offers a nightmarish vision of a mainframe computer with excessive autonomy, which almost annihilates the world when it confuses a simulation for a real-war scenario, or rather when its operators fail to detect its confusion. The difference is moot, but telling. The capacities of this machine had evolved since the 1970s: the graphical simulations of missile strikes on the array of world maps are in motion, and a new soundscape of computational activity – electronic bleeps and chirrups – is ushered in. The billboard-sized screens that we see in this film will also become a staple in later narratives as will the corresponding sight of computer operators facing not just their own immediate screen or screens, but also one or more large-scale screens mounted against the wall of the control room.

Cybersyn, along with The Andromeda Strain, THX-1138, and the control rooms and user interfaces they feature, present a threshold between the linear, hierarchical, purely rational logic of the modernist dream on the one hand, and the cybernetic future and its complex, non-linear, feedback logic on the other. This shift towards the complexity paradigm begins to take place in this era, and reflects the changing nature of conflict in general. In organization studies literature of the final decades of the 20th century, we repeatedly see traces of a transition from ‘design principles derived from the classical scientific (Newtonian-Cartesian) paradigm [to] the complexity science paradigm’, (McMillan, 2002: 123-36) with the result that ‘behaviour patterns that are highly conditioned by boundaries between levels, functions, and other constructs [are] replaced by patterns of free movement across those same boundaries’ (Mabey, 2011: 164; see also Corbett et al., 2002; and Wilson, 1997). In line with these changes, the literature of sociotechnical systems and of human-computer interfaces describe the transitions that very large organizations underwent during the same period, and up to the present, from slow-moving, centralized, hierarchical monoliths to dynamic, change-oriented, horizontal networks. Changes in organizational management are manifested in control room design in the form of autonomous yet networked computers, advances in real-time technology, and audio-visual hardware capable of faster processing and improved sounds and displays.

1992–present: From Control Room to Control Node

Between 1983 and 1992, the nine-year gap between WarGames and Patriot Games, the number of personal computers per capita increased fourfold in Britain and Japan, and fivefold in the United States (source: World Development Indicators Database Nationmaster). Although most control room scenes of the 1990s still featured mainframe computers as opposed to desktop devices, and although the Internet had not yet become established among non-specialists (the World Wide Web became operational in December 1990), the control room imaginary in this period starts to shift from an architectonic to a purely computational logic.

A pivotal moment in this era is the well-known scene in the 1992 film Patriot Games, where an attack is launched by special forces on a ‘terrorist’ camp in the Sahara. The film’s hero Jack Ryan and his colleagues witness the attack via satellite in a restricted room deep inside the CIA building. Jack is brought there with no explanation of what he is about to see, other than that he is going ‘into battle’. As it slowly dawns on him that he is witnessing a real-time, live attack, Jack turns to look at his two superiors as if to ask, ‘Is this really what I think it is?’ His questioning look arises from the shock of immediacy that the technology creates. The technology on display here is highly reminiscent of short blurry videos of ‘precision bombing’ released one year before by the US during the first Gulf War, and of aftermath images such as Fig.12. Until now, Jack Ryan had been viewing these desert scenes at a distance, in the sterile environment of the CIA’s still photography lab, and he is shocked to discover the existence of manipulable spy satellites, remotely located ‘pilots’, high-speed data streams and high resolution live-action cameras.

What was new in the 1990s was a growing tendency to view the world, and narratives about the world, in line with what in military discourse is called ‘Command and Control.’ Often abbreviated to C2, the term refers to the application of cybernetic thinking to military affairs, whereby decisions are made on the basis of feedback loops of information that are made available by communications technology (Alberts and Hayes, 2006). With the passage of time, the concept has expanded to C3I (Command, Control, Communications and Intelligence), then to C4I (with the addition of ‘Computing’) and to an unwieldy plethora of emendations, such as C4IFTW (Harris and White, 1987; Department of Defense, 2010: A20-21). Patriot Games and other early 1990s films such as Eve of Destruction (1991), Sneakers (1992) and Universal Soldier (1992) come at the midway point of the cultural change that James Der Derian identifies between the late 1970s and the 2000s, a period of:

digitally enhanced virtual immersion, in which instant scandals, catastrophic accidents, impending weather disasters, ‘wag-the-dog’ foreign policy, constructive simulations, live-feed wars, and quick-in, quick-out interventions into stillborn or moribund states are all available, not just primetime, real time, but 24/7, on the TV, PC, and PDA. … Facing new hyper-realms of economic penetration, technological acceleration, and new media, the spatialist, materialist, positivist perspective that informs realism and other traditional approaches could not begin to fully comprehend the temporal, representational, deterritorial, and potentially dangerous powers of virtualism. (2001: 209, emphasis in original)

Der Derian’s description may have a touch of hyperbole, but when we jump ten years on from Patriot Games, Steven Spielberg’s Minority Report (2002) makes Der Derian’s analysis seem positively subdued. The hero of Minority Report is a detective in a futuristic police force that can detect crimes before they happen. To do this, he operates a data screen, mixing information from real and virtual sources by moving his networked gloves but without touching anything. The screen enables him to combine police databases with visions of future crimes that are drawn from super-sensory humans who are kept in a state of suspended animation as their brains are scanned for information about the future. Not only have we entered the era of the haptic interface and seamlessly interconnected databases by 2002, but we have also witnessed an ontological shift insofar as the control room and its interfaces have become portals to virtual places that are remote geographically and temporally, both from the protagonist and the viewer.

A more extreme instance of this virtuality appears in the control room of the 2006 science fiction/terrorism thriller Déjà Vu, where a secret government research unit of physicists has built a jumble of screens, cables and computers that makes it possible to view past events that have not explicitly been recorded, and to transform its screens into future-seeing ‘time windows’. When the hero shines a laser beam through the latter, it is seen by a character in the future, who acts upon seeing it and thereby creates an alternative future. The paradoxical cybernetic logic on display here, where recursivity produces emergent properties that were not present when the system was initiated, is achieved to a large degree by the look and feel of a key emblem of this era: the Fantasy User Interface (FUI, pronounced ‘phooey’).

Mark Coleran, the visual effects designer of Déjà Vu, is also responsible for the FUIs (Figs. 15-19) in control room scenes in The World is Not Enough (1999), The Bourne Identity (2002), AVP: Alien vs Predator (2004), The Island (2005), Mr and Mrs Smith (2005), Children of Men (2006), Mission Impossible III (2006) and The Bourne Ultimatum (2007). The FUIs on display in these films enable a scientific, or scientific-seeming, gaze that visualizes features of an environment that are otherwise invisible (infra-red, nano-scale, informational, unrecorded, behind corners, etc.). The FUI often renders bodies, objects and buildings transparent, producing schematic images of them that can be rotated on several axes.

In some cases (see Figs.17-19), reams of numbers will appear in the FUI to indicate vast data sets, referring to concepts such as geographical location and vital life signs, as well as moving, pulsating grids and other indicators of measurement and coordinates. The FUI is so extravagant, the computations that take place in it are so complex, so all-seeing and so transparentizing that it can do the work that the control room used to do. They are the fulfillment of what Scott Bukatman identified as long ago as 1993 as a ‘terminal identity’, whereby the boundaries of the human being become indistinct as data become embedded in our vision of ourselves and of the world. The FUI interface is not simply a fictional display screen. As part of a cybernetic system that includes humans and machines, it is the aestheticization of emergence, the process in which a system takes on properties (such as future-vision) in an autonomous fashion that it did not previously have.

Iron Man (2008) brings together many strands of change in cinematic control rooms of the previous decade. The technological exoskeleton of the Iron Man suit also features the soft, flexible qualities usually associated with software, such as the part-solid/part-virtual screen interface (also in Minority Report and The Matrix Reloaded), the dynamic solid-yet-digital 3D pin-display of X-Men (2000), the holographic display-interface of Star Wars: Revenge of the Sith (2005) and Prometheus (2012), and the semi-organic hardware of Source Code (2011), which had been anticipated in eXistenZ (1999), Pi (1998), Cronos (1993), The Lawnmower Man (1992) and Videodrome (1983). In Iron Man, the control room of the US military is a hard-wired anachronism from which it is impossible to keep up with Stark’s technology, while the hero Stark’s own control centre consists of a much more fluid, panoptic 360-degree set of screens. What is more, Stark’s technology includes a tabletop that produces holographic projections that he can then manipulate manually. An even more fully immersive environment is presented inside the Iron Man suit itself, where all of the visual and tactical aids that a control room normally provides are projected in front of the user’s eyes in the form of a head-mounted-display (HMD).

Here we can see the influence of computer-game mise-en-scène, which often provides data to the player alongside the action on screen in what is called a heads-up-display (HUD). In a conventional control room, the FUI is seen either in a point-of-view or over-the-shoulder shot. But fully transparent and semi-transparent screens onto which are projected images and data that are increasingly prevalent both in the fictional universe (cf. the control room of Avatar (2009), the display surfaces of Oblivion (2013), The Island and Quantum of Solace (2008)) and in consumer items (cf. Google’s Project Glass HMD, the Samsung AMOLED transparent flexible display, and the Microsoft PixelSense/Samsung Surface SUR40 combination, and the windscreen HUD in BMW vehicles – see Fig.20), which place the viewer in what Norah Campbell (2007: 7-8) calls an ‘impossible’ subject position on one side of a veil of technologized data, and make cyborgs of us all. Indeed, when ‘material objects are interpenetrated by information patterns,’ what Katherine Hayles calls a ‘condition of virtuality’ is attained (1999: 14, 20), precisely along the lines of the ‘neural interface systems’ envisioned in current military neuroscience research (Royal Society, 39-40).

What does this portability promote, permit and promise in terms of changes to the legal-political imaginary? On the evidence of films and shows such as Die Hard 4.0 and 24 (we could add Enemy of the State (1998), the Mission Impossible series (1996-) and the Bourne trilogy (2002-07)), the control room is paralleled, and perhaps even superseded, by a shifting, networked control node whose advanced computational capacity is expressed by a dazzling FUI. The hero can act independently with a piece of portable technology that can plug into a network and is not centrally controlled or even monitored.

The sociotechnical literature on military strategy describes exactly this change, most succinctly in the doctrine of Network Enabled Capability (NEC) (Walker et al., 2008), which envisions

self-synchronizing forces that can work together to adapt to a changing environment, and to develop a shared view of how best to employ force and effect to defeat the enemy. This vision removes traditional command hierarchies and empowers individual units to interpret the broad command intent and evolve a flexible execution strategy with their peers. (Ferbrache, 2003: 104)

On the one hand, this is simply a description of a C4I environment where, for instance, a targeting system may involve communication from a satellite to a drone that analyses data onboard without the need for mediation by a control room on the ground. On the other hand, it represents a totally different understanding of the nature of contemporary conflict. An NEC-type apparatus pertains to real-world conflict, but as we have seen, an apparatus such as a control room contains multiple discursive as well as material components. The discursive fictions that are attached to such an apparatus are therefore inseparable from it. In this view, agents such as Jack Bauer of 24 or John McClane of the Die Hard films are archetypes of the new type of conflict that usually posits ‘terrorism’ of some description as its strategic enemy.

In the literature on ‘terrorism’, both from hawkish policy-focused think tanks and dovish cultural critics, the common perception, particularly in the post-2001 era, is of a polymorphous or amorphous enemy (Zanini et al., 2001; Knorr Cetina, 2005; Urry, 2002; Dillon, 2002; and Galloway and Thacker, 2007). Such thinking sees the conflict facing the west as an escalating spiral of technological specialization, where each side increasingly prioritizes network-theory values, such as mobility, adaptability, spontaneity and connectedness, at the expense of traditional military capabilities, such as battlefield tactics, firepower or physical speed. As Eyal Weizman (2007: 185-220) makes clear in his critique of the adaptation by the Israeli Defence Forces of their tactics under the influence of Deleuzo-Guattarian deterritorialization and other non-linear concepts (nomadic space, fractal manoeuvre, lines of flight, etc.), postmodernism’s buzzwords and concepts are not intrinsically liberatory. Indeed, at times quite the opposite is true. High-technology systems and the patterns of thinking that go with them, where one finds a ‘new sovereignty of networks, control, and the fetish of information’ (Galloway and Thacker, 2005: 2) lead Alexander Galloway to ponder whether network-thinking has been absorbed by the very systems it once seemed to undermine:

Networks, rhizomes, ‘grass roots’ movements — these were all effective diagrams for political control under modernity. But after the powers-that-be have migrated into the distributed network, thereby co-opting the very tools of the former Left, new models for political action are required. A new exploit is necessary, one that is as asymmetrical in relationship to distributed networks as the distributed network was to the power centres of modernity. (Galloway, 2006: 320)

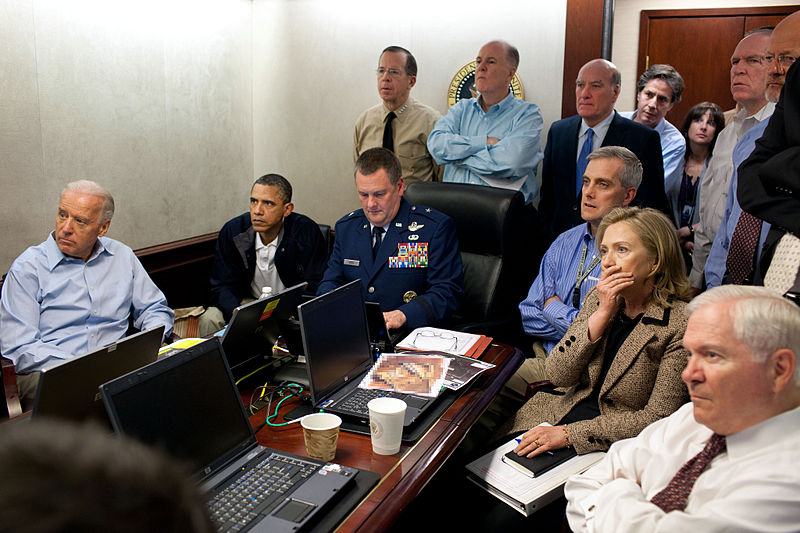

Network-thinking seems to question the sovereignty of the powers-that-be by identifying discrete nodes as sovereign actors. This may be bad news for old hierarchies, but it brings with it a danger of a distributed, and ultimately unaccountable, type of sovereignty that is deemed necessary when there is a state of permanent conflict or permanent emergency. Good examples of this are Carrie Mathison of Homeland and Jack Bauer of 24 who are at their most effective when not obeying the chain of command. The sovereignty of the organs of state, and of course of the president, become distributed phenomena in the era of NEC because it does not channel decision-making upwards to a sovereign entity (as in Fig.22) but operates as a semi-autonomous node, such as a special forces unit or a drone bomber. In the era following 11 September 2001, we see an almost compulsive need to create drastic, far-reaching and at times exotic control room situations – for instance, 24, The Dark Knight (2008), and Source Code (2011) – where all possible resources are employed to stave off attack. The contemporary control room may in this light be characterized in post-Fordist terms; that is, decentred, ad hoc, networked, or, as being made up of components that are ‘fast, cheap and out of control’, to use Rodney Brooks and Anita Flynn’s description of robots designed for space exploration (Brooks and Flynn, 1989). In a state of perceived permanent emergency, such as the ‘war on terror’, it becomes a challenge to ‘identify the legal framework and sources of law applicable to the current conflicts in which drones are employed’ (Vogel, 2010: 102; see also Mayer, 2009; and Pugliese, 2011). So when Osama bin Laden was killed in a US special forces raid in May 2011, the argument about Pakistan’s breached sovereignty was a distraction from what the event said about power under NEC. Thus the photograph (Fig.21) released by the White House of Barack Obama and his senior officials watching the events unfold is in this light a portrayal of sovereignty ensconced in its operations room contemplating its own demise.

In a sense, there is little new about the problematic legality of the use of drones and of the Obama Administration’s Disposition Matrix, the name given to the constantly evolving CIA database of terrorist suspects and of the resources available for capturing or killing them (see Miller, 2012). The drone is simply the current apotheosis of a century of military technological inventions – submarines, chemical weapons, airpower in general, nuclear weapons – that have repeatedly disrupted the possibility of establishing legal boundaries in conflict. In the post-World War II era, conflict readiness is always switched on. So even if war is not actually engaged, it is permanently virtually engaged, and as a result the legal-political exception becomes the norm. The control room, in its civilian and its military applications (Figs. 23 and 24), is the material manifestation of this same process of mediatization by which the difference between actual and virtual contact with reality becomes difficult to discern.

Conclusion

The crisis in international law initiated by submarine warfare, airpower and chemical weapons has never been resolved, and is only exacerbated by drone power. In the current era, ‘the “viewing screen” now occupies a central place and has become indispensable for those who wage remote war’ (Gregory, 2011). Yet, it was clear as early as the Hague Conferences of 1899 and 1907 that what Carl Schmitt calls ‘Eurocentric international law’ (2003: 49) needed radical updating to keep up with these new technologies, which ignored (among other things) long established land and sea boundaries, rules of booty, and the difference between combatants and non-combatants. What Schmitt identified, both during his Nazi years and after World War II, was that the affordances of new war technologies are always fully exploited in times of crisis – this explains unrestricted submarine warfare, strategic bombing of urban populations, and the use of the atomic bomb in Japan. What is more, the meaning of ‘crisis’ itself becomes altered by a range of technologies, such as drones, that can be maintained in constant battle readiness.

It comes as no surprise that Schmitt, the legal theorist who is so keenly aware of the degradation of politics when it is rendered as a technocratic problem, is also so perceptive when it comes to seeing how a decision-making sovereign is necessary to ‘rescue’ us from liberal democracy. If we translate the exceptionalistic logic of Schmittian sovereignty, whereby the sovereign becomes sovereign by deciding when a state of emergency exists, into spatial terms, we recognize a ‘phenomenology that is structurally analogous’ in the dizzying mise en abyme of screens and their embedded windows. Sovereignty is simultaneously seized and established by the entity that steps outside the existing paradigm and establishes a new reality. As long as the state of exception is perpetual, as is the case in the ‘war on terror’, the field is permanently open for any decisionistic actant (room, node, president, hero, network, etc.) to step outside the law and to define the contours of a new legal regime.

Perhaps the greatest change that took effect as a result of the attacks on the US of 11 September 2001 is the way that it made explicit the permanence of the ‘war on terror’. To be sure, the concept of ‘terrorism’ had been given enormous intellectual, institutional and political sustenance since the 1970s (Stampnitzky, 2013), so it was ready for action, so to speak, when it was needed (Jackson, 2012). A political atmosphere such as this causes critical thinkers to reach for the Schmittian dual insight that power is, effectively, always up for grabs, and that it comes with the capacity literally to legitimize itself. The error to avoid is to posit a legal situation that ought to be:

There is no more a free-floating jurisprudence than there is a free-floating intelligentsia. Legal and jurisprudential thinking occurs only in connection with a total and concrete historical order. Also, there cannot be free-floating rules or free-floating decisions. (Schmitt, cited in Ulmen, 2006: 20)

In this light, the intellectual structure that he provides, particularly when treated in the Foucauldian spirit of biopolitical critique, is ideal for media archaeological investigations. This conjuncture is also where Agamben positions himself in his multi-volume Homo Sacer project, and indeed there is a striking passage cited at length by Agamben in The Kingdom and the Glory where a metaphorical-cum-architectonic description of the ‘imposing administrative apparatus of the king of the Persians’ (2011: 71) reads very much like an analogue for sovereignty in the era of command and control.

If ‘control room’ signifies a particular combination of architecture and hardware, it also, in a single phrase, signifies a meshing of jurisprudence, communications, media technology, networks, sovereignty and space. As a result, it becomes possible to speak about the confluences that occur in what Der Derian (2001) calls the Military-Industrial-Media-Entertainment Network (MIME-NET) while avoiding de-politicizing anecdote and hyper-politicizing conspiracy theory. The development of closed-circuit television, for instance, can be properly inserted into the engineering history of remote control, as it was invented for observing V2 rockets in Germany in 1942 (High et al. 2014: 62) and significantly developed in 1943 as a visual aid for crane operators handling dangerous materials in the facility that produced nuclear materials for the Manhattan Project (Sanger, 1989a and 1989b), just as it can be inserted into the histories of traffic control, wildlife management (Benson, 2010: 192), bank security, prisons, public spaces, underwater oil exploration, underwater Hollywood extravaganzas (The Towering Inferno (1974), The Abyss (1989), Titanic (1997)), paranoid Hollywood thrillers about surveillance (Three Days of the Condor (1975), The Conversation (1974)), reality television shows and, of course, drones (Mirzoeff, 2011: 492).

Finally, the media archaeological approach suggested here may offer some signposts towards future manifestations of power and future arrangements of techno-aesthetic form. If the latest control room scenes offer a view of complexity in the ascendant, perhaps we should watch the same space for new configurations of power beyond complexity. The ‘same space’ may of course not be a control room at all, especially as the evidence suggests that the materiality of the control room is becoming less architectonic. The fields of radical technological upheaval that we can anticipate now – such as nanotechnology, cyborgism, genetic manipulation, quantum computing and biosemiotics – all seem to spell an end to dichotomies of hardware and software, material and concept, reality and code, body and mind. However, we ought to be wary of the grammatizing dream of information and the information sciences, which is the promise of pure remote control and an end to the encumbrance of materiality.

References

Agamben, G. (2011) The Kingdom and the Glory: For a Theological Genealogy of Economy and Government. Trans. L. Chiesa. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Alberts, D. S. & Hayes, R. E. (2006) Understanding Command and Control. Command and Control Research Program.

Aradau, C. (2010) ‘Security that matters: Critical infrastructure and objects of protection’, Security Dialogue 41 (5): 491-514.

Benson E. (2010) Wired Wilderness: Technologies of Tracking and the Making of Modern Wildlife. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Brooks, R. A. & Flynn, A. M. (1989) ‘Fast, Cheap and Out of Control: A Robot Invasion of the Solar System’, Journal of the British Interplanetary Society 42: 478-85.

Bukatman, S. (1993) Terminal Identity: The Virtual Subject in Post-Modern Science Fiction. Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press.

Campbell, N. (2007) ‘The Technological Gaze in Advertising’ Irish Marketing Review 19 (1&2): 3-18.

Corbett, L.M. et al. (2002) ‘Thinking and Acting: Complexity Management for a Sustainable Business’ in G. Frizelle and H. Richards (eds), Tackling Industrial Complexity: The Ideas that Make a Difference. Cambridge, UK: Institute of Manufacturing. 83-96.

Department of Defense (2010) Dictionary of Military and Associated Military Terms (amended March 2014). Washington, D.C.: Joint Publication 1-02.

Der Derian, J. (2001) Virtuous War: Mapping the Military-Industrial-Media-Entertainment Network. Boulder: Westview.

Dillon, M. (2002) ‘Network Society, Network-Centric Warfare and the State of Emergency’, Theory, Culture & Society 19 (4): 71-9.

Edwards, P. N. (1996) The Closed World: Computers and the Politics of Discourse in Cold War America. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Esposito, R. (2011) Immunitas: The Protection and Negation of Life. Cambridge, Polity.

Ferbrache, D. (2003) ‘Network Enabled Capability: Concepts and Delivery’, Journal of Defence Science 8 (3): 104-07.

Foucault, M. (1979) Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Trans. Alan Sheridan, London: Penguin.

Foucault, M. (1980) Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings 1972-77, Colin Gordon (ed.) New York: Pantheon.

Fuller, M. (2005) Media Ecologies: Materialist Energies in Art and Technoculture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Galloway, A. (2006) ‘Protocol’, Theory, Culture & Society, 23 (2&3): 317-320.

Galloway, A. & Thacker, E. (2005) ‘Sovereignty and the State of Emergency’, Kritikos 2 (July). Available at: http://intertheory.org/thacker-galloway.htm.

Galloway, A. & Thacker, E. (2007) The Exploit: A Theory of Networks. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Gillispie, C. C. & Alder, K. (1998) ‘Engineering the Revolution’, Technology and Culture 39 (4): 733-54.

Gregory, D. (2011) ‘Lines of Descent’. Open Democracy, 8 November. Available at: https://www.opendemocracy.net/derek-gregory/lines-of-descent.

Harris, C. J. & White, I. (1987) Advances in Command, Control and Communication Systems. London: Peregrinus.

Hayles, N. K. (1999) How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Heidegger, M. (2003) ‘The Question Concerning Technology’ in Philosophical and Political Writings, Manfred Stassen (ed.) New York: Continuum, 279-303.

High, K., Hocking, S. M., & Jimenez, M. (eds) (2014), The Emergence of Video Processing Tools: Television Becoming Unglued. Bristol: Intellect.

Huhtamo, E. & Parikka, J. (eds) (2011) ‘Introduction: An Archaeology of Media Archaeology’ in Media Archaeology: Approaches, Applications, Implications. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Jackson, R. (2012) Writing the War on Terrorism: Language, Politics and Counter-terrorism. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Knorr Cetina, K. (2005) ‘Complex Global Microstructures: The New Terrorist Societies’, Theory, Culture & Society 22 (5): 213-34.

Mabey, C et al. (2011) ‘Organizational Structuring and Restructuring’, in Graeme Salaman (ed.), Understanding Business: Organisations. London: Routledge.

McCormick, J. P. (1997) Carl Schmitt’s Critique of Liberalism: Against Politics as Technology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McMillan, E. (2002), ‘Considering Organisation Structure and Design from a Complexity Paradigm Perspective’, in G. Frizelle and H. Richards (eds), Tackling Industrial Complexity: The Ideas that Make a Difference. Cambridge, UK: Institute for Manufacturing.

Martin, R. (2005) The Organizational Complex: Architecture, Media, and Corporate Space. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Massumi, B. (2010), ‘The Future Birth of the Affective Act: The Political Ontology of Threat’, in Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth (eds), The Affect Theory Reader. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 52-70.

Mayer, J. (2009) ‘The Predator War: What are the Risks of the C.I.A.’s Covert Drone Program?’ The New Yorker, 26 October. 36-45.

Miller, G. (2012) ‘Plan for Hunting Terrorists Signals U.S. Intends to Keep Adding Names to Kill Lists.’ The Washington Post, 23 October.

Mirzoeff, N. (2011) ‘The Right to Look’, Critical Inquiry 37 (3): 473-96.

Morgantini, Maurizio (1984), ‘Man Confronted by the Third Technological Generation’, Design Issues 1 (2): 21-25. Nationmaster (n.d.) ‘World Development Indicators Database: Personal computers (per capita)’. Available at: http://www.nationmaster.com/country-info/stats/Media/Personal-computers/Per-capita.

Noys, B. (2015) ‘Drone Metaphysics’, Culture Machine 16.

Pugliese, J. (2011) ‘Prosthetics of Law and the Anomic Violence of Drones’, Griffith Law Review 20 (4), 931-961.

Royal Society (2012) Neuroscience, Conflict and Security (Brain Waves Module 3). London: Royal Society.

Ruoff, H. W. (1918) The Book of the War. Boston: Standard Publication Company.

Sanger, S. L. (1989a) ‘Lombard Squires’s Interview’ Voices of the Manhattan Project. Available at: http://www.manhattanprojectvoices.org/oral-histories/lombard-squiress-interview.

Sanger, S. L. (1989b) ‘Ray Generaux’s Interview’ Voices of the Manhattan Project. Available at: http://www.manhattanprojectvoices.org/oral-histories/ray-genereauxs-interview.

Schmitt, C. (2004) [1932] Legality and Legitimacy. Trans. J. Seitzer. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Schmitt, C. (2005) [1934] Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty. Trans. G. Schwab. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Schmitt, C. (2006) [1950] The Nomos of the Earth in the International Law of the Jus Publicum Europaeum. Trans. G.L. Ulmen. New York: Telos.

Stampnitzky, L. (2013) Disciplining Terror: How Experts Invented ‘Terrorism’. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stiegler, B. (2014) Symbolic Misery – Volume One: The Hyperindustrial Epoch. Cambridge: Polity.

Ulmen, G. L. (2006) ‘Introduction’ in Schmitt, C. (2006) [1950] The Nomos of the Earth in the International Law of the Jus Publicum Europaeum. Trans. G.L. Ulmen. New York: Telos, 9-36.

Urry, J. (2002) ‘The Global Complexities of September 11th’, Theory, Culture & Society, 19 (4): 57-69.

Väliaho, P. (2014) ‘The Light of God: Notes on the Visual Economy of Drones’ NECSUS, European Journal of Media Studies, Autumn. Available at: http://www.necsus-ejms.org/light-god-notes-visual-economy-drones/.

Virilio, P. (1986) Speed and Politics. New York: Semiotext(e).

Vogel, R. J. (2010) ‘Drone Warfare and the Law of Armed Conflict’, Denver Journal of International Law and Policy 39 (1): 101-38.

Walker, G. H., Stanton, N. A., Salmon, P.M. & Jenkins, D. P. (2008) ‘A Review of Sociotechnical Systems Theory: A Classic Concept for New Command and Control Paradigms’, Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science 9 (6): 479-99.

Weizman, E. (2007) Hollow Land: Israel’s Architecture of Occupation. London: Verso.

Wilson, F. A. (1997) ‘The Brain and the Firm: Perspectives on the Networked Organization and the Cognitive Metaphor’, Proceedings of the Pacific Asia Conference of Information Systems 1997, 581-87.

Winner, L. (1986) The Whale and the Reactor: A Search for Limits in an Age of High Technology. Chicago: University of Chicago. World Development Indicators Database (n.d.) Personal computers per 1000: Countries compared. Available at: http://www.nationmaster.com/country-info/stats/Media/Personal-computers-per-1000.

Zanini, M. et al. (2001) ‘The Networking of Terror in the Information Age’, in John Arquilla and David Ronfeldt (eds), Networks and Netwars: The Future of Terror, Crime, and Militancy. Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2001, 29-60.

My contribution to this special issue is accompanied by a video essay, A Short History of the Cinematic Control Room, 1971-2015, available here: https://youtu.be/hswm-1wkODw